In the early hours of 28 October 1967, the co-founder of the Black Panther Party, Huey Newton, was pulled over by police as he was driving along Seventh Street in West Oakland, California. A scuffle ensued and shots rang out, puncturing Newton’s abdomen, killing a police officer, John Frey, and wounding another.

All bullets found at the scene were police-issued, yet Newton was arrested as he was being treated for gunshot wounds in hospital, and sent to jail. His prosecution and 1968 trial sparked the “Free Huey” protests that spread across the country, transforming the Panthers into a nationwide Black power organization demanding an end to police brutality, equality in housing and employment, and an economic revolution.

After three trials, two of them ending in hung juries, prosecutors gave up and dropped all charges. By then, the Black Panther party was indisputably on the map.

Fifty-six years later, in the exact same spot on Seventh Street where the shootout occurred, a new Black Panther is emerging. Where blood once stained the sidewalk, shiny steel and tinted glass now dominates the block as an $80m business and affordable housing project enters its final months of development.

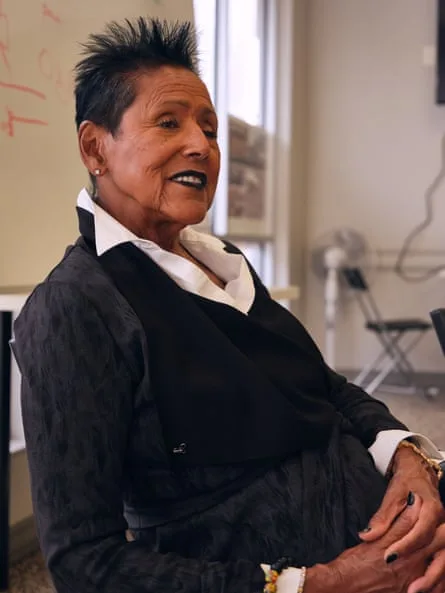

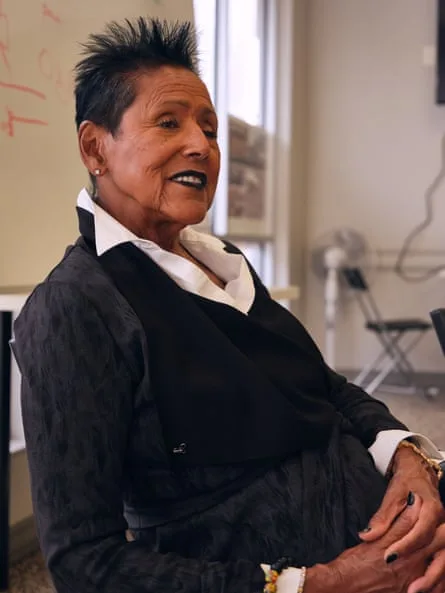

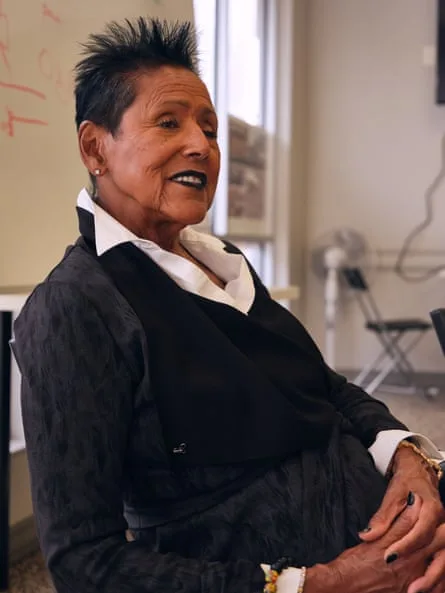

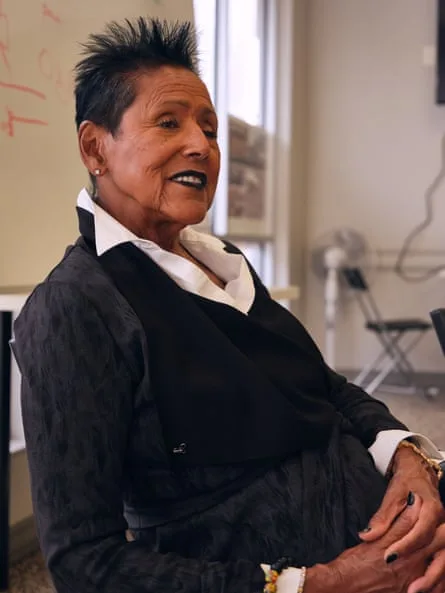

Its creator is Elaine Brown, an activist, writer and singer who in 1974, when Newton went into exile in Cuba, became the only woman ever to lead the Black Panther party. Now 80, she proves to have as much fire in her belly as she did back in the heady days of the Black liberation struggle, though this time her immediate focus is not revolution but providing jobs and low-cost homes to those who need them.

“Don’t misunderstand me,” she told the Guardian, sitting in her office in the multi-million dollar project she is cajoling into life. “I’m still the same person I was in the Black Panther party – though maybe more ruthless.”

Brown insisted that the decision to pick this historically potent location for her new development was entirely coincidental. “It was serendipity,” she said.

But having settled on the Seventh Street block between Campbell and Willow Streets, she is making the most of past narratives. She is calling the project the Black Panther, and when the complex opens in May, that name will stand proudly in 3ft-high letters above the main entrance.

Brown said that what had moved her to build the 32,000-sq-ft project in West Oakland was exactly the same motivation that propelled her leadership of the Black Panthers in the 1970s. “My goal then and my goal now is to create a model and an idea that will raise consciousness and give people something to fight for,” she said.

Seventh Street used to be a vibrant African American neighborhood with a thriving economy boosted by the rise of the Port of Oakland as a major second world war naval shipyard, which drew large numbers of Black people to the area from the US south. The street bustled in the 1940s and 50s with music venues playing west coast blues, Black-owned banks, a Black movie theater and the headquarters of the first Black labor union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

The area was affectionately known as the Harlem of the west.

Then the neighborhood was rent asunder, like so many other Black communities labelled “blighted” or “undesirable”, by a number of government-promoted infrastructure schemes that literally tore it apart. First came a double-decked highway in 1957 known as the Cypress Street Viaduct that bisected the area, followed in 1960 by a gargantuan and dystopian-looking post office building that razed 12 square blocks to the ground, destroying 400 homes and businesses.

The final blow was delivered in 1974 with the opening of the West Oakland station of the Bart rapid transit system, the last stop before San Francisco. The Bart ran on elevated tracks all the way along Seventh Street, shattering the area with noise and snuffing out what remaining communal life was left.

By the time that Brown’s non-profit, Oakland & the World Enterprises, bought the land for redevelopment, it had been vacant for 30 years.

Brown’s priority is to try to resurrect some of the economic vitality of the Harlem of the west by opening spaces for new Black-owned businesses. On the ground floor of the building, there will be a restaurant, fitness and tech centers, as well as a grocery store to help address the local food desert.

She expresses the need for new business opportunities in characteristically forthright terms. “I want us, Black people, to have economic power. We live in an environment where we have nothing. Black people don’t own anything in America. Not a goddamn thing. We are still an oppressed people, but we won’t recognize it.”

The businesses will be run as cooperatives, with every worker offered an ownership interest and with jobs reserved for poor or formerly incarcerated people. California’s prisons disproportionately lock up African Americans: 29% of male prisoners are Black, while they make up only 6% of the state’s adult male population.

“One of the reasons people are in prison is because they are poor; they are there for economic crimes,” Brown said. “The only way to stop them going back into prison after release is to get them some money and a job.”

The other focus of the Black Panther will be 79 units of affordable housing that will fill the upper stories. Studios and one- and two-bedroom apartments will be offered to very-low and extremely-low income people, with a maximum limit on their earnings set at 30% of the area’s median income (about $30,000 a year).

With support from the city of Oakland and California, all 79 apartments will be offered at low or extremely low rents. “Nobody else in West Oakland or anywhere else in this city has 100% affordable housing, can you believe that?” Brown exclaimed.

For a former revolutionary leader whose language is still today peppered with quotes from Vladimir Lenin and Mao Zedong, it is striking how much of the funding for the Oakland development has come from that hated enemy: the government. Of the Black Panther building’s $80m costs, about $61m has come from the state of California, $43m of which was drawn from a new housing accelerator program designed to fast-track low-cost housing projects struggling for lack of funds.

The program was part of the state’s response to a profound housing and homelessness crisis of which Oakland is very much a part. More than 5,000 people in the city are homeless – an 131% increase on 2015. Forty-three per cent of unhoused people in Alameda county, where Oakland sits, are Black.

Brown accepts that, in themselves, 79 new affordable homes are not going to touch the scale of the crisis. “This is not a panacea of any kind. There are thousands sleeping on the streets of Oakland every night, and thousands more on somebody’s couch or sleeping in their car.”

But she says the project will stand as a statement that everybody has a right to a place to live. In that, she is drawing a straight line to the 10-point manifesto of the Black Panther party written in 1966 by Newton and the party’s co-founder Bobby Seale.

Point 4: We want decent housing fit for the shelter of human beings.

Her vision for Seventh Street is framed by the racial justice revolution to which the Panthers aspired. “As the Black Panther party said, and as I say today, the people are the makers of revolution. I don’t make revolution with my little project right here,” she said. “But when these masses of sleeping, oppressed people rise up and demand housing, then they will get it. That is my goal.”

Brown joined the Black Panther party in 1968 in Los Angeles in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King and the police killing of Bobby Hutton, a young Panther, in Oakland. She studied revolutionary theory and the Panthers’ platform for Black empowerment, and rose quickly through the ranks to join the party’s central committee as minister of information and editor of its newspaper.

Though the Panthers have been criticized for being male-dominated – with their fondness for guns and uniforms of leather jackets, black berets and shades – much of the most enduring work of the party was led by women. Brown was central to setting up many of the movement’s so-called “survival programs”, including the breakfast program that provided free food to Black school children; the Panther liberation school in Oakland, which taught kids not only academic excellence but also about Black pride and anti-colonial freedom movements; and the free medical advice and busing-to-prison programs.

In the early years of the Panthers, she suffered the fierce attrition of the FBI, unleashed by the bureau’s director, J Edgar Hoover, who in 1969 declared the party “the greatest threat to internal security of the country”. Several of her comrades and friends were killed, including Fred Hampton Sr, the party’s deputy chair, who was shot in his bed in Chicago in 1969.

As a singer-songwriter, Brown recorded two albums during the Panther years, Seize the Time (1969) and Until We’re Free (1973). She also turned her hand to electoral politics, running unsuccessfully for the Oakland city council in 1973 and 1975, and in 2007 briefly bidding to be the Green party’s presidential nominee.

She is best known for her stint as chair of the Black Panther party between 1974 and 1977. She was handed the role by Newton as he fled to Havana to escape prosecution for allegedly murdering a child prostitute in Oakland.

In her 1992 memoir, A Taste of Power, Brown describes the extraordinary measures she had to take to overcome sexist resistance among male Panthers to a female party leader. She recalls a confrontation in which she forced a prominent party member to obey her orders at the barrel of a gun.

“A woman in the Black Power movement was considered, at best, irrelevant,” she wrote. “If a black woman assumed a role of leadership, she was said to be eroding black manhood, to be hindering the progress of the black race.”

Newton returned from exile in 1977. Brown describes in her book how, less than a year later, she abruptly quit the Panthers and Oakland, unable to bear the patriarchy and sliding values of the party any longer.

To this day Brown continues to perceive the challenge ahead through a radical lens not dissimilar to that of the vanguard party she used to lead. She sees the Black Panther development in West Oakland not just as the creation of affordable housing and desperately needed jobs, but as a chance to change minds.

“So I’m a developer now. People are like, ‘Oh, she raised $80m and can talk with a big stick.’ That doesn’t mean anything to me – what is $80m?”

What does mean something to her is striving towards a more fundamental shift. “I’m trying to concretize the idea of owning our own lives and destinies. Black people have got to be self-determining – we cannot continue to beg white people for our livelihoods. We are in the same position today that essentially we were in in 1865.”

Just like the breakfast program, she hopes that the Seventh Street development will inspire people to start demanding more. “If you get something that you need, what now, goddammit?” she said.

“I got breakfast, I want lunch; lunch, I want dinner; dinner, I want a place to live; place to live, I want medical care; medical care, I want education. Then, as Lenin said, the moment comes when the oppressor cannot accommodate you. That’s when the people will be ready for revolution.”