For the past 25 years, the name Zappala has been synonymous with law enforcement in Allegheny County.

As one of the longest-serving district attorneys in Pennsylvania, Stephen A. Zappala Jr. has set the tone for criminal justice for a generation of lawyers, police officers, judges and criminals.

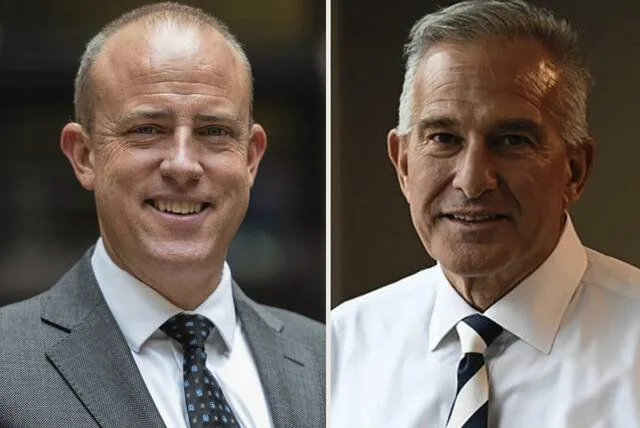

That could change next month when voters in 130 communities choose between keeping the veteran top prosecutor in office or starting fresh with Matt Dugan, the county’s former chief public defender

Dugan thrashed Zappala in the primary to earn the Democratic nomination for the post, but Zappala — who said he’s still a registered Democrat — secured enough Republican write-in votes to become the GOP nominee.

In lengthy interviews with the Tribune-Review, each candidate made his case to be the county’s chief law enforcement officer.

Their differences are stark.

Zappala, seeking a seventh term, said he despises progressive policies like those embraced by his challenger. He calls the progressive agenda a “virus” that erodes public safety by abandoning victims, coddling criminals and failing to enforce the law. He warned that Allegheny County would suffer if he loses the Nov. 7 election.

“I think it’ll be San Francisco and Philadelphia within a year, maybe two years,” Zappala said, echoing a talking point often embraced by the right that paints progressive prosecutors in those cities as a major driver of crime. “It means they’re going to destroy everything that we’ve put together.”

Dugan, who is riding the crest of a yearslong effort by progressives to topple Zappala, dismisses such rhetoric as a gross misrepresentation of his reform-minded goals. He said he wants to change a criminal justice system that he believes is rife with fundamental problems and built-in inequities that hobble the poor and minorities.

“That does not mean that we’re not going to arrest people who break the law. That does not mean there’s not going to be accountability when people break the law,” Dugan said. “What it means is we need to do a better job of differentiating between low-level, non-violent offenders and people who are really out there causing harm to our society.”

Dugan said his opponent has gotten too comfortable during his long reign and runs a disorganized, stagnant office that lacks leadership. He points to claims by Zappala that racial profiling does not occur in Allegheny County and that in all his time as district attorney, his office has never had a wrongful conviction out of tens of thousands of cases.

“It shows a level of arrogance, quite frankly,” Dugan said. “It shows that he’s really out of touch.”

Zappala scoffed at Dugan’s barbs.

“I know from the rhetoric from my opponent, he has no idea how to protect people,” Zappala said.

A district attorney wields enormous power. Whoever occupies the third-floor office in the county courthouse will be a linchpin in what happens across 16 courtrooms, dozens of district judges’ offices, roughly 100 police departments, the DA’s investigations unit, and any active grand juries. The DA’s office itself is a $22 million operation with more than 100 attorneys.

And the candidates have vastly different visions for how to run it.

“I’m talking about building a better system where we can have more just outcomes and where it is public safety-centered,” Dugan said. “We understand that our chief function is to protect public safety. We just think that there are ways we can better be helping our folks who find themselves in the criminal justice system because of substance abuse, mental health and poverty issues.”

By contrast, a win by Zappala would represent stability, a known quantity and, the way he sees it, a powerful advocate for violent crime victims.

“I’m the one that takes care of them,” Zappala said. “Nobody has done more for victims’ rights than I have.”

Joseph Sabino Mistick, a Duquesne University law professor who taught both candidates and has served under several Pittsburgh mayoral administrations, laid out the fault lines in the race.

“There’s no close call here. These aren’t subtle differences,” Mistick said. “I would say we have on the one side a law-and-order Democrat with some traditional values and attitudes toward criminal justice, and on the other side we have a candidate who believes it’s time for some dramatic change, that criminal justice nationally has been headed in the wrong direction, and it’s time to revamp.”

Different ideologies

Many progressives believe that the existing system of mass incarceration, cash bail and a lack of true diversionary programs after arrest hasn’t improved society. Opponents portray progressives as soft on crime and partial to policies that stymie police.

In San Francisco, voters frustrated by property crimes and the city’s homeless population recalled their progressive district attorney partway through his term.

Philadelphia’s district attorney, Larry Krasner, stopped prosecuting almost all simple drug possession cases. That, along with a surge in crime and violence, led Republican legislators to impeach him, but Commonwealth Court rejected the effort.

While Zappala’s and Dugan’s campaigns have firmly staked out their places along this ideological divide, trying to pigeonhole their politics is another matter. Dugan views himself as more of a “common-sense” candidate than anything. And Zappala, a lifelong Democrat, accepted the Republican nomination after Dugan defeated him in the Democratic primary.

The race has taken a nasty turn, with Zappala launching two TV ads that feed into fear-mongering and bogeymen. One cycles through grainy videos of violence and looting, purportedly in San Francisco and Philadelphia, and warns that Pittsburgh will be next under a “social justice experiment” by “extremists” supported by Dugan.

The other, playing off a legal brief written by one of Dugan’s former subordinates on behalf of a state defense attorneys group, claims Dugan has told rape victims to “shut up” — something Dugan categorically denies.

The district attorney has enlisted Brabender Cox, a Republican political consulting firm, and adopted a standard GOP tactic of attacking his opponent for accepting campaign money from George Soros, the billionaire who has donated tens of millions of dollars to progressive prosecutors’ campaigns around the country.

The son of a doctor and a nurse, Dugan, 44, of Moon Township, grew up the oldest of four children in Beaver County. He studied law at Duquesne University and upon graduation eschewed working as a prosecutor or at one of the city’s white-shoe law firms.

“That’s not where I was needed,” Dugan said.

Instead, he went for low-paid criminal defense work. Dugan was the first intern at the then-new Office of Conflict Counsel, which represents indigent defendants when the public defender’s office has a conflict of interest.

Frank Walker, president of the Pittsburgh Black Lawyers Alliance, was Dugan’s mentor there 20 years ago. Now he supports his protege’s bid for DA — not just because he respects Dugan’s zeal and likes his ideas, but because he’s had enough of Zappala’s.

“All the problems of the last 25 years, he’s blaming someone else,” Walker said of the DA. “It boggles my mind.”

Similar starts

Dugan moved to the public defender’s office and then steadily climbed the ladder until he was appointed in 2020 to take over for his predecessor, Elliot Howsie, who became a judge.

Zappala ascended to his position in similar fashion. The 66-year-old from Fox Chapel was appointed to fill a vacancy when Robert Colville, himself a longtime district attorney, took the bench.

Zappala’s selection came through a closed-door vote by Allegheny County Common Pleas Court judges. Unlike Dugan, who had a wealth of criminal trial experience, Zappala specialized in municipal and civil law.

He possessed an intangible that his earliest critics never failed to note: Zappala’s late father and namesake was a state Supreme Court justice and former Allegheny County judge; his grandfather had served in the Legislature.

Once ensconced at the county courthouse, Zappala cast himself as an administrator, not a litigator. One of his first actions made clear that he wouldn’t shrink from tough decisions: He fired his rival, the most experienced homicide trial attorney in the office, and then thumped him in the next election.

After that, for years, Zappala sailed into office unopposed.

“I really didn’t run,” he said. “I just kind of was on the ballot.”

That changed in 2019, when he faced the first primary challenge in two decades. His opponent was Turahn Jenkins, the chief deputy public defender.

Jenkins was part of a group of young progressive criminal lawyers who sought to oust Zappala and reform the system. The issues then were much the same as now, focusing on cash bail, mass incarceration and what to do with low-level offenders.

Zappala beat Jenkins handily in the primary, but would face a November challenge from another progressive attorney, Lisa Middleman. A longtime public defender, Middleman made a late entry and ran as an independent in the general election. Although she lost by 14 percentage points, progressives felt like the two challengers exposed a weakness in Zappala’s armor.

Lengthy track record

Zappala has pointed to his success in establishing specialized courts to adjudicate cases involving veterans, drug users and those with mental health issues. Supporters laud him for encouraging police to wear body cameras, prioritizing initiatives against domestic violence and writing a victim’s bill of rights that has been enshrined into law.

John Rago, a law professor at Duquesne University, has worked extensively with Zappala on legislation involving body cameras and, as a member of the Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing, on issues involving harsher sentences for fentanyl-related crimes.

“The reason we have body cameras in Pennsylvania is because of Zappala’s push. I was in the room,” Rago said. “Zappala came to us before fentanyl became a front-page story every day and said, ‘We need to do something about fentanyl.’”

Zappala created units in his office to address domestic violence crimes and child abuse. He prides himself on gathering stakeholders to solve problems and assembling task forces to combat crime.

That track record wasn’t enough to sway Democratic Committee members to support him during this election cycle. The committee threw its backing behind Dugan and then voters followed suit in the primary.

Sam Hens-Greco, chairman of the county’s Democratic Committee, called it a “resounding statement” by voters who sought a “fresh start.”

“I think they were tired of the current administration, the Zappala administration, and they wanted somebody who was going to look at the office in a different light,” Hens-Greco said.

Zappala did not present well when he appeared before committee members, according to Hens-Greco.

“He was very uninspiring. He was dismissive to people when they would ask questions. He did not talk about things he had been successful with in office. It almost seemed like it was difficult for him as a candidate to be out in front of people,” Hens-Greco said.

In the primary, Zappala snagged enough Republican write-in votes to put him on the November ballot. He accepted the GOP nomination, even while aligning himself with the nonpartisan Forward Party.

Sam DeMarco, the county’s Republican chairman, is happy to have Zappala running as his party’s candidate. He said he remains optimistic that more moderate voters will help propel Zappala to victory despite the 2-1 registration edge that Democrats have over Republicans in the county.

“I feel good in that I believe that the people who are engaged understand what’s at stake and are willing to reelect Steve Zappala to be the district attorney,” DeMarco said. “I think a lot of that should be based on the increasingly leftward lurch of the far-left in the Democratic Party, meaning the progressives and the socialists which seem to be driving it today.”

Problems Downtown

In a sometimes-heated interview sprinkled with profanity, Zappala railed against Pittsburgh Mayor Ed Gainey and his predecessor, Bill Peduto, claiming their progressive policies have led to a crumbling sense of security in the Golden Triangle.

“I never had problems with our criminal justice system until these guys created problems … these progressives, whatever they are. It’s a virus,” Zappala said.

Progressives, he added, are causing problems “all over the country.” He described Gainey and Peduto as “ultra-left” politicians who fail to follow the broken-windows theory of policing, which holds that left unchecked, minor crimes such as vandalism will lead to danger and violence.

“You enforce those laws. If you don’t, nothing good happens. Blight turns into more serious crimes. Public urination turns into open lewdness turns into sexual assault turns into all this other stuff,” Zappala said.

Complaints about crime Downtown have been pervasive even as statistics show no appreciable change since 2018, according to Pittsburgh police data.

Quality-of-life problems have taken root and proven to be tough to eliminate. Drug trafficking, drug use, prostitution, panhandling, vagrancy, homelessness and the presence of trash, urine and excrement all have soured business owners.

To some, the occasional violent crime and the perception of a lack of safety have created a pall over the Golden Triangle.

But homicides have been few and random attacks rare, police say.

In discussing Downtown crime, Zappala pushed back on any notion that he might bear responsibility as the longtime district attorney.

“I cannot police. I can’t enforce quality of life crimes. I can’t enforce property crimes,” Zappala said. “What I considered doing was putting the city on notice that I will seek the federal government’s help and put them in some kind of receivership like they had before, and then have some committee oversee realistic policing in the city.”

Zappala declined to elaborate. He said he had a plan to address problems Downtown, but he refused to divulge it to the Tribune-Review. He admitted that he had not presented his secret solution to any officials in city hall amid frustration with the Gainey administration.

Whether progressive policies are to blame for any rise in crime rates is up for debate. A study released last year by the University of Toronto looked at 65 American cities and found no link between progressive prosecutors and homicides.

“This whole focus on holding prosecutors to account, progressive or otherwise, for a city’s homicide rate, is entirely misguided,” said Richard Rosenfeld, one of the study’s authors. “I don’t know of a single progressive prosecutor, either in office or while campaigning for office, who has argued that they’re going to back off homicides. It’s a non-issue.”

Rosenfeld and his colleagues also looked at the impact of progressive prosecutors on the rate of larcenies — the type of low-level crime that critics fear will snowball if left unchecked. The study found no correlation.

“The issue for me is will a progressive prosecutor in office lead to higher levels of crime, and the answer appears to be no,” Rosenfeld said.

In addition to lashing out at the mayors, Zappala targeted District Judge Xander Orenstein, who sparked controversy last month when he released a New York man arrested with what police said was $1.6 million in fentanyl. The suspect did not have to put up any cash or collateral, and then he failed to show for a court hearing. He is now the subject of a nationwide arrest warrant.

Orenstein’s actions were roundly criticized — including by Dugan.

But Dugan laid into Zappala for not making a case to keep the suspect jailed during his initial court appearance.

Like other progressives, Dugan objects to cash bail. It’s ineffective, he claims. But he said that doesn’t mean he wants to send violent or dangerous criminals back to the streets while they await court hearings.

“I don’t care how much money they have in their bank account or how much collateral they’re willing to post,” Dugan said. “If they’re a risk to public safety, they shouldn’t have the opportunity to be released.”

The Soros factor

A favorite punching bag for progressive opponents is billionaire George Soros and his Justice and Public Safety PAC, which has poured millions into progressive prosecutor campaigns across the country, including the Allegheny County race.

“Most of these prosecutors pursue radical justice policies upon assuming office including eliminating bail, dismissing felony cases and seeking lenient sentences while creating antagonistic relationships with their public safety partners, especially the police,” according to a report by the pro-police Law Enforcement Legal Defense Fund.

Through the May primary, Dugan had received more than $700,000 of in-kind contributions from Soros’ political action committee, according to campaign finance filings, but he rejects the notion that he’s going to warp his priorities to fit someone else’s demands.

Dugan said his message has been consistent. A groundswell of local support, sparked in part by the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020, put the race on the national radar, Dugan said, and Soros liked what he saw.

“No one has put a word in my mouth,” Dugan said. “These are policies and prescriptions that are unique to Allegheny County.”

Zappala portrays himself as above the fray. Abandoned by his party? That’s politics, he says. Running as a Republican? It doesn’t mean anything, he insists.

“I’m not a politician, man. I don’t care about all the political issues that you’re talking about,” Zappala said. “My concern was, I listened to Dugan, and I listened to Middleman prior to Dugan, she was substantially funded by Soros-type people. They are dangerous. And they’re following a playbook in return for the money. They’re following a playbook that has failed all over the country.”

Hens-Greco isn’t buying it.

“He’s wedded himself to the Republican Party, which right now is wedded to Donald Trump,” Hens-Greco said. “There are values in the Republican Party that they stand by. They have a platform, and if you’re going to be a candidate for that party, then you’re carrying water for that party.”