WASHINGTON, D.C. — Under the white dome of the Capitol, the normally routine legislative process is thrown into chaos.

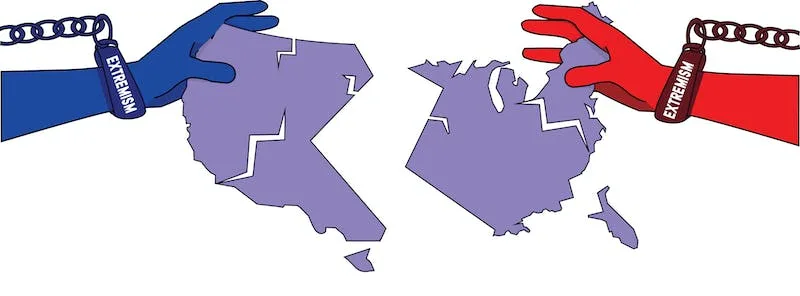

As congresspeople argue about the budget planning, leadership, international intervention, support and so much more, polarization and extremism make it harder and harder to find compromise and hold the center.

What does compromise mean?

United States Rep. John Moolenaar (R-2nd) said the idea of a center means different things to different people.

“I think in a situation where we have a divided government, you need to come to some kind of a resolution … to get bills signed into law, you need bipartisan support,” Moolenaar said.

Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-6th) said that each of the representatives has different perspectives and life experiences, which leads them to viewing impacts of things differently.

“Finding that common ground can often give you a good piece of legislation,” she said.

U.S. Rep Rashida Tlaib (D-12) said, whether the decision was a compromise or not, it’s important to consider its final impact.

“We need to look at the end result,” Tlaib said.

Dingell said even disagreements can be civil, and that true problem solvers can find common ground.

“I’m going to keep doing what I’m doing, to talk to people on all sides,” Dingell said.

Stacey LaRouche, a press secretary for Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, said it’s on everyone to “turn down the heat,” and focus on working together.

“Michigan is home to Republicans and Democrats,” LaRouche said. “There’s no district, there’s no part of the state that’s 100% Democrat or 100% Republican, so it’s important to be able to … work to serve constituents.”

Where do common interests lay?

Michigan is a purple state, where a lot of people fall in the middle, Dingell said.

According to the Michigan Secretary of State, in the most recent Michigan gubernatorial elections in 2022, Democrat Whitmer received 54.47% support while her Republican opponent, Tudor Dixon, had 43.94% of votes. In 2020 presidential elections in Michigan, 50.62% of registered voters cast a ballot for President Joe Biden and 47.84% for incumbent Republican Donald Trump, according to secretary records.

In fact, over the past four presidential election cycles, the state has turned out — if only by the most narrow of margins — in favor of the eventual winner.

With the 2024 presidential primary looming, Michigan Democratic lawmakers voted in January to move the state to be fifth in the nation to hold primary elections. The party’s electors will head to the polls Feb. 27 to cast their ballots, according to the National Conference of State Legislators. That puts the state one week ahead of so-called “Super Tuesday.”

However, liberal or conservative labels are “loaded,” and depend on how people define them, Rep. Tlaib said. Some think that they are progressive, but don’t support progressive issues, she said.

“I’d like to see people work together, keep community strong,” Dingell said. “United we stand, divided we fall.”

LaRouche said Whitmer has done a lot of bipartisan work in lowering costs in the face of inflation and road constructions.

“We’ve seen in Michigan, extremism doesn’t work,” LaRouche said. “People just want to see leaders get things done.”

There are some issues where both parties can find a common interest, Moolenaar said. He has worked on legislation to restore the Great Lakes and to clear barriers to health care for member of the Native American community.

LaRouche said since Whitmer took the office, she signed over 1,000 bipartisan bills.

However, College Democrats at Central Michigan University President Katie Gibson said on issues like abortion, the parties stay divided.

“There’s no means of communicating within those two parties and coming to a central agreement,” Gibson said. “People are so focused on this extreme value thing, there’s going to be no room for conversation to close that gap.”

Polarization in the government and mind

LaRouche likewise said abortion is one of the issues on which the Michigan governor will not compromise.

“We had so many Republicans come to these round tables and join the conversation,” LaRouche said. “In fact, there was a Republican woman … who explained how she had never voted for a Democrat before, but because of abortion rights, she was out knocking doors for Gov. Whitmer last year.

“There are some issues that cut across all political lines.”

College Republicans President Evan Gibeau said other polarizing issues include student loan forgiveness and immigration.

“We’re seeing a lot of people far right, who have extreme views, and a lot of people on the far left, who have extreme views,” Gibeau said. “One end of the spectrum wants to completely close (border) off, and the other one wants to completely open it. I think there’s a definite lack of communication and compromise in government right now.”

Moolenaar said the U.S. should prioritize the security of the Southern border when passing the budget plan.

“We have to tighten up the border so that there’s no drugs coming across,” he said.

However, Gibson said toughening the Southern border will not work.

“This whole idea of closing the border, if anything, just incites more illegal immigration,” Gibson said. “I think putting more resources into those who are seeking asylum or those who get deported … ensuring that they’re getting to a safe place so that they don’t try re-enter. … They’re just going to keep coming back if they’re not safe in their country.”

The border priority came up when planning the national security budget funds. The Republican party is debating of what interests U.S. should prioritize, Moolenaar said. The debate also included earlier bipartisan aid to Ukraine.

“I think it has been important that the United States has helped Ukraine defend itself,” Moolenaar said. “I think it’s also important that for the American taxpayers (to see where) taxpayers’ dollars are used to support Ukraine … (there) needs to be accountability and transparency.”

Dingell said U.S. should continue support Ukraine, because “it’s about fighting for democracy in the world.”

Then, in late September, as the federal government stood on the edge of shutting down because of its budget bill, a divided Congress kept the nation on hooks. Former Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy (R-California) struck a deal that kept the government running for another 45 days, but earned the ire of extreme members of his party and cost him his leadership.

“We want to keep the government open,” Moolenaar said ahead of Sept. 30 compromise. “We want to secure the border. We also want to look at this long-term debt problem. … We’ve wanted to reduce spending because of the debt … and inflation.”

Similarly, Dingell fought to avoid the shutdown.

“You’re watching now total chaos and drama (over) whether the government will continue to be funded, which isn’t acceptable and not a way to run anything,” she said.

The rise of extremism

Tim Alberta, the author of the “American Carnage: On the Front Lines of the Republican Civil War and the Rise of the President Trump” and a writer for The Atlantic, said extremists exist in both parties. However, leadership of the Republican party has been captured by an extremist mentality, which makes the Republican party fall further right than Democrats far left, he said.

“Extremism in American politics is nothing new,” Alberta said.

Extreme views existed when the U.S. was founded and during the American Civil War, he said.

In this new era, a different form of extremism emerged at the end of George W. Bush’s presidency in 2008. Wars, beginning of economic collapse and the first African American president — all came over a short period of time, Alberta said.

“(White suprematism) really created the conditions for a new wave of extremism in our politics, (in) particular conservative politics,” Alberta said. “(The) party … began to embrace an angry militant populism that ultimately manifested itself in Donald Trump.

“But the signs were there long before Trump came along.”

Heidi Beirich, a writer for the nonprofit civil rights think tank Southern Poverty Law Center, said white supremacists’ race-based movement started in 2000, and accelerated in response to Barack Obama’s presidency.

However, for a long time, neither Republicans nor Democrats wanted to associate themselves with those extremists – not until Donald Trump came to power, she said.

Still, Gibson said Trump set the stage for the extreme values.

“I think the issue with the Republican extremism skyrocketed after Trump,” she said.

How much did Trump damage the middle ground?

America saw what happens without common ground when Trump was in office, College Democrats President Gibson said. Trump had a number of people who “didn’t fact check” information under his influence, and followed him into Jan. 6 Capitol attack.

“Trump set the stage … for future presidents to act in a way that presidents shouldn’t,” Gibson said. “I think more outrageous ideas are going to be thrown out there … . I think it’s going to be chaos.”

Trump-style leadership is not a uniquely American phenomenon, Beirich said. Rather, she said, the “Trumpian world out there” exists in the faces of leaders of Hungary, Brazil, India and others.

“They come to power through elections, but their platforms are intended to reduce the civil rights protections of various populations,” Beirich said. “Once they get into power, they become more autocratic.”

Trump was able to influence the population — Americans the below poverty level included — even though he despises those who are below the poverty level, Beirich said. That also had historical and psychological patterns, she said.

“I think that there are people trying to destroy this country by the division of fear and hatred,” Dingell said. “I think Donald Trump is trying to divide this country.”

Trump also caused the divide in the Republican party of those who want him in the office and those who do not, College Republicans’ Gibeau said.

“There’s definitely a divide because people who are pretty far right tend to call everybody who’s in what typically considered normal conservatism 30 years ago … ‘RINOs,’” Gibeau said. “And I think that’s a very degrading term.”

Moreover, Gibeau said, some Republican face stereotypes about them.

“One of the stereotypes is that everybody who’s right-leaning is homophobic, racist, transphobic,” Gibeau said. “I find a lot of people, especially in College Republicans, aren’t really focused on more of the social issues … I think a lot of people are more moderate that the news would make them out to be.”

The polarization “is feeding off” things like social media, cable news and misinformation that further divides people, Alberta said. However, he added that American institutions are strong, and the country has been through a deeper division before.

“I certainly think that in his first term, Donald Trump tested our institutions in ways that we had never seen, at least not in modern history,” Alberta said. “A second Trump presidency would be even more damaging to those institutions, our civic norms, that we would be even further divided.”

Will the center hold?

Gibeau said people who are on the far on both sides of spectrum have “a really loud voice.”

“The party divide has grown … it’s moving further in both directions,” he said. “It’s a lot harder to find people who are moderate. I think we’re losing sight of where the center is.”

Even through elected officials don’t like compromising, there is a potential for American people to find common ground, Gibson said.

Younger generations became politically aware in the times of extremism, Alberta said.

“Young people are the ones inheriting the world,” LaRouche said. “Young people really see what is at stake, and they’re getting engaged and participating in our democracy.”

Both Gibeau and Gibson said people of their age tend to support Democrats.

According to Gallup’s website, Generation Z votes 31% Democrat and 17% Republican.

But throughout the history, things are cyclical, Alberta said. If one party gets a great victory in the elections, the other likely will have its win in the next ones.

Similarly, even though young people vote Democrat today, they might vote Republican when they get older, Alberta said.

What is different, the young generation is more diverse, Beirich said.

“That doesn’t mean that the politics might not become more conservative as people get older when they have different issues on their mind,” Beirich said. “But what won’t change is a rejection of racism and white supremacy – that’s not something that’s going to shift as somebody goes from being 20 to 50 (years old).”

However, the young generation will only come to power in about 10 or 15 years, Beirich said, and it is hard to say whether the center will hold through that time.

“There’s so much stacked up against it, and so much really actually rides on this election in 2024,” Beirich said. “It’s a pivotal moment.”