By David Childs

Northern Kentucky University

In expressing his stance against slavery, Kentuckian Abraham Lincoln stated, “the world has never had a good definition of the word liberty, and the American people, just now, are much in want of one. We all declare for liberty; but in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing.”

David Childs

Lincoln’s statement rings just as true today as it did in the 1800’s. Indeed, people seem to mean different things when discussing notions of freedom and liberty. In his time Lincoln was one of the central figures of the freedom struggle and was indeed born in the state of Kentucky. To be more specific, he was born south of Hodgenville, Kentucky, in Larue County.

For many Kentuckians one of the greatest presidents to ever live resided right in their hometown. Although we often view historical events as taking place in some far away land, they are often not far from us if we know where to look. One of the principles I always teach my university students is that “history is often local.”

As a professor of history and education, a large part of my charge is to work with K-12 and university students to stress the importance of local history and its connections to our larger world. In my college days my instructors always emphasized the fact that local history is connected to regional, national and international history, even current events. But historical research often starts right in our communities. Studying history from this perspective personalizes the knowledge and helps know better where we came from, where we are and where we are going.

Abraham Lincoln’s childhood home at Knob’s Creek (Photo/Abraham Lincoln Birthplace/National Historical Park/Kentucky)

This approach to historiography and educational studies has sparked the research that has been going on at Northern Kentucky University (NKU), facilitated by a partnership between the Black Studies, Public History and the Education departments. This work is a collaboration with Drs. Brian Hackett, Burke Miller, Jennifer Morris and three graduate students, including Derrick Thomas, Jamie Thompson, Jennifer Williams, and others. Like Lincoln’s connection to Kentucky and local history, the study of African American history in general and the Underground Railroad specifically, largely took place in Northern Kentucky and southern Ohio.

Indeed, our region is one of the premiere geographical regions for the study of Underground Railroad history. NKU researchers have been working to uncover African American history throughout Kentucky and Ohio that can give us insight into our past, present and future as Americans. This has led me and a team of graduate students to have an opportunity to highlight this work at a conference at the National Museum of African American History at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC.

I often remind my students that even though Kentucky never left the union and joined the confederacy, it still was a slave-owning state. Thus, one can stand to reason that much of the Underground Railroad activity took place in Kentucky, along the Ohio River on the borderlands. As such, enslaved people successfully escaped slavery, fleeing from Kentucky to free states like Ohio and beyond.

An advertisement from 1850 featured a runaway from Livingston County, near Mount Vernon. Like many of the advertisements for runaways, it offered a detailed description, describing the enslaved man (Manuel) as being 35 years old, 5 ‘7 in height and 160lb. A reward of $200 was offered for those that captured Manuel. In another advertisement in 1859 an enslaver was trying to reclaim a woman he purchased who was from the Lexington area. Throughout the 19th Century many ads like this were posted by enslavers highlighting familiar areas of Kentucky such as Covington, Louisville, Maysville and various counties.

This gives insight into the fact that in Kentucky, many Blacks took it upon themselves to fight against slavery on their own terms, often by escaping. Hardin County, Kentucky author and historian Alicestyne Turley in her book entitled The Gospel of Freedom: Black Evangelicals and the Underground Railroad challenges the popular romanticized myth that white abolitionists were the primary leaders of the Underground Railroad. We now know that Blacks, through their own agency, were largely in charge of the freedom and abolitionist struggle, playing a much larger role than we once thought.

St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Augusta (Photo provided)

One of the center projects we will highlight at the Smithsonian is research in Augusta, Kentucky, involving restoration of a historic Black church (St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church) from the 19th Century with ties to an enslaved community. The work highlights a remarkable woman (Sarah Thomas) who had been enslaved, gained freedom, and went on to become an entrepreneur, business woman and a founder of the church.

Our goal (in partnership with the notable Clooney family) is to restore the church to its original state and transform it into an African American cultural arts center and museum.

Similarly, the NKU team will also highlight work we are doing at an antebellum church in New Richmond, Ohio, that had connections to the Underground Railroad. Furthermore, we will discuss our work and writings on Sarah Mayrant Fossett and her husband Rev. Peter Fossett, who had been business owners and founders of the first Black church in Cincinnati. The couple played a major part in the abolitionist movement in Kentucky and Ohio.

Another project we will highlight is archeological work the public history department has been doing at the site of the former Parker Academy, also in New Richmond. Founded in 1839, Parker Academy was believed to be the first school in the United States to offer fully integrated classrooms open to all races, religions, and genders.

This work we will present in Washington will impact the academic community, the general public, but most importantly the K-12 community. Classroom teachers can help their students learn, understand and appreciate a fuller U.S. historical narrative.

If we can tell the broader American story we can help bridge some of the great divides in our nation surrounding equality. In this way, we can understand that the American story is multicultural, including experiences of a diversity of people groups throughout history. Curricula can be expanded in K-12 and college classrooms to offer a more intellectually honest picture of our own history.

I am reminded of a quote from Louisville native Muhammed Ali (originally named after the famed abolitionist Cassius Clay). Ali was frustrated by the overt racism he experienced in his hometown, and in his classic way, highlighted the hypocrisy and senselessness of racism.

He said, “I came back to Louisville after the Olympics with my shiny gold medal. Went into a luncheonette where black folks couldn’t eat. Thought I’d put them on the spot. I sat down and asked for a meal. The Olympic champion wearing his gold medal.

“They said, “We don’t serve [Blacks] here.” I said, “That’s okay, I don’t eat ’em.”

“But they put me out in the street.

“So I went down to the river, the Ohio River, and threw my gold medal in it.”

Ali’s story, and thousands of other local stories like his make up the kind of history that we should be learning in our schools.

Much of history is local, and when we learn about our own past it can help us become better citizens, better Americans, better Kentuckians and better humans.

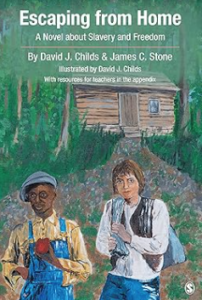

David Childs, Ph.D., has been a member of the social studies and history faculty at Northern Kentucky University since 2012. He was the first African American in the College of Education to earn tenure at NKU. He is an undergraduate of Mount Saint Joseph University, holds two master degrees, and earned his doctorate at Miami University of Ohio in African American history, educational leadership and philosophy, and an honorary doctorate in theological studies from Temple Bible College and Seminary in Cincinnati. He is the co-author of the book, Escaping from Home, a novel about slavery and freedom, available from Amazon. He is director of Black Studies at NKU, and he and fellow professors and students are presenting a research study at the Smithsonian on the role the Ohio River played in slavery and the Underground Railroad.