After Game 8 of a best-of-seven series that was soaked with controversy and chaos, Philadelphia emerged victorious.

In 1934, the Philadelphia Stars faced off against the Chicago American Giants for the Negro National League Championship. The Stars came back to Philadelphia and their home field — where West Philadelphia High School now stands — down 3-1 in the series after playing the first four games in Chicago.

Then, the drama began. There was a seemingly inexplicable 10-day delay before Game 5, which the Stars won. They won again in Game 6, even though two Stars players got into separate physical altercations with umpires and somehow escaped ejection. Game 7 ended in a 4-4 draw due to darkness because baseball stadium lights were uncommon at the time. Both teams ended up filing protests with the league after the series finished.

The next day, in the decisive Game 8, the Stars’ Slim Jones pitched a 2-0 shutout, winning the title for Philadelphia.

The Inquirer wrote about Jones’ performance at the time:

“[He] twirled the [Stars] to the loop diadem with his speedball and baffling cross-fire to turn in six strikeouts, but he also put the game on the proverbial ice when he blasted in the final run with a sharp single to left in the seventh.”

The Stars were dismantled by the end of the 1952 season, as integration of Major League Baseball made it impossible for the Negro league teams to survive. The team delighted and enthralled Philly’s Black community for fewer than 20 years, but the Stars’ presence meant more than just seeing a group of men play a game.

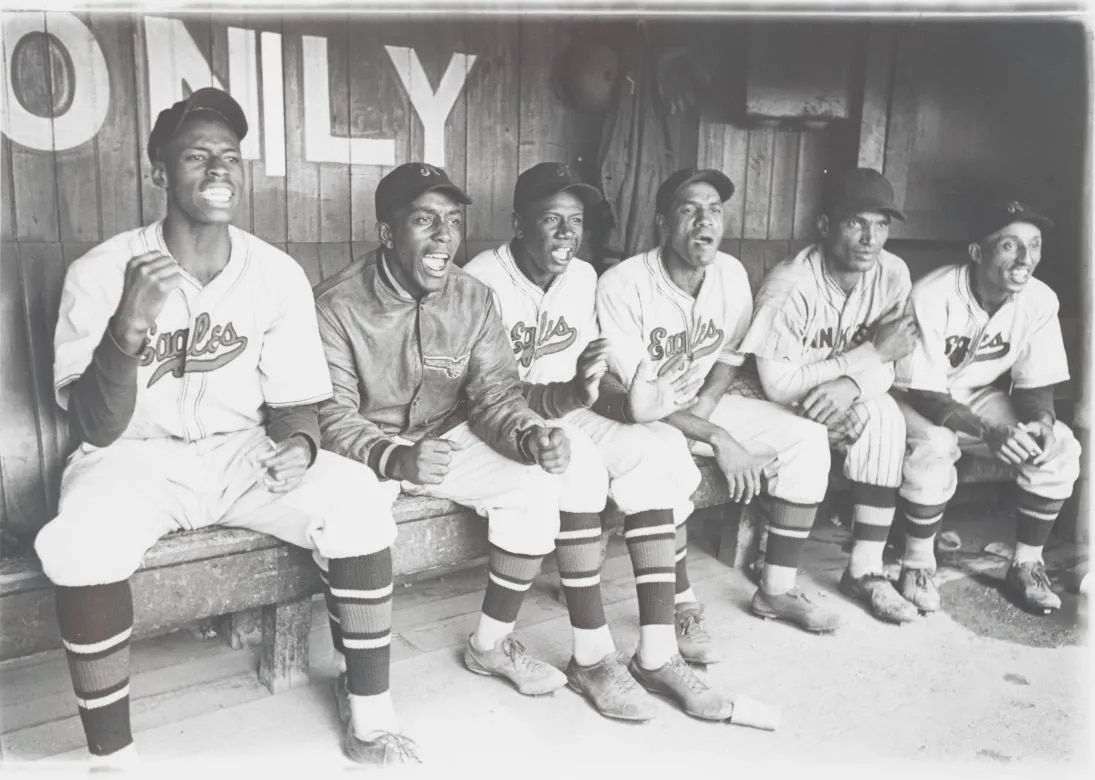

A new documentary executive produced by Questlove and Black Thought is making sure that the impact and rich history of the Negro baseball leagues is known. The League features newly unearthed archival footage and interviews with some of the negro leagues’ most important figures, like Satchel Paige and Hank Aaron.

The director of The League, Sam Pollard, spoke with The Inquirer about the new documentary, how entire economies were built around the Negro baseball leagues , and why Jackie Robinson’s story was a complicated one.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What made you interested in telling this story about the Negro leagues, particularly at this moment in America where Black history is being challenged?

For those of us in the community, Black people, people of color, it’s an eye opener to [realize] that we had our own teams. We had our own players. They were phenomenal. You know, there wasn’t just Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. There was Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige and Max Manning and Buck Leonard and James “Cool Papa” Bell.

The thing about sports is that you also learn about what’s the emotional and psychological things that you need to be the best that you can be in these games. What’s the challenges you face when you play opposing teams or opposing players? What did it mean to be a Black person playing in these particular sports at a time of ugly segregation? You’re finding heroes, you’re finding villains, you’re learning the history of America.

It’s about knowing that there’s aspects of American culture that weren’t just about George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.

Rube Foster, the creator of the first Negro National League, designated its official motto, “We Are the Ship, All Else the Sea”, an ode to a Frederick Douglass line. What does that phrase mean to you? And what did the Negro leagues mean to Black communities?

Foster knew that by creating the Negro National League, he was doing something very important in the world of sports. [He knew] they were gonna be at the forefront of leading African Americans into baseball. It was exciting to know that there was a man with the gumption and the energy and the focus to bring together all these different owners who had all their [singular] teams and to make them a strong entity.

Think about it. We lived in these segregated communities in Philadelphia, New York, in Tulsa, Los Angeles, where we had to figure out how to survive, how to engage ourselves, how to have our own businesses. And we did that.

We had an outlet. We could go to the church, we could go to the nightclub, we could go to a sports game. As Bob Kendrick said [in the film], people would leave church early to go to those baseball games on Sunday, all dressed up. These teams brought money into the community, [including] other businesses, which [helped] stabilize these Black [neighborhoods] for many, many years.

These players were loved. They were seen as stars, but they were [also] seen as people from the community. You could go play a game and then you could go hang out at night at a club and see people. You might have been a wonderful ballplayer on the field during the day, but at night you were just part of your community.

The documentary discusses how Jackie Robinson’s story and the integration of the Major Leagues didn’t come without a cost. The Negro leagues themselves were shuttered and the economies built around them collapsed. How did Black people think about that trade-off at the time?

Being a Black person in America is complicated. On the one hand, there was those of us who probably said, wow, it was great that Jackie integrated the Major Leagues, [just like] in 2008 when Obama became president. You become a member of the Major League team. You become president of the United States.

But what’s the downside to that? There [were] those of us who felt that Obama wasn’t aggressive enough. He wasn’t forward-thinking enough for Black people. There were probably those who were happy and excited Jackie went to the Major Leagues, which meant then, as fans, they would not go to Negro League games.

We’re not a monolith, we all have different attitudes about things. There might have been people in the Black community who thought, well I’m not gonna go to Major League games, even though Jackie integrated the game. And then [the Negro Leagues] became like dinosaurs and they were gone.

For me, it’s always exciting and a real pleasure to delve into our stories. We learn so much about America on one level, but we never learn about the America that you and I know.

The League will be available in AMC theaters on July 9, 10, and 12 and available to stream on July 14.