For too long, the conversation about slavery has become overshadowed by bad-faith actors. While descendants of the enslaved in the Caribbean and the Americas continue to hold former colonisers accountable and build cases for reparations, former slave-holding nations have been pushing back furiously, suggesting it’s not just impossible to remedy the horrors of slavery, but irrelevant too, given how “long ago” it was.

These are debates that have been happening for centuries. Yet it’s become increasingly clear that one significant group hasn’t featured as prominently in the global discussion: leading African voices. At last, this is starting to change.

Take, for example, President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo of Ghana who, just a fortnight ago, told the UN General Assembly it was time for the nation to receive reparations, arguing “no amount of money would ever make up for the horrors, but it would make the point that evil was perpetrated”. He also confirmed that an African Union Conference on reparations will be held in Accra in November of this year – pushed back from an earlier proposed date in October.

Whenever African leaders speak up on the issue, they are often confronted with the same criticisms, the most common being that Africans should not receive reparations because – as the counterargument goes – they are the descendants of enslavers. I have written previously in i about why such counters are simplistic at best and intellectually incoherent at worst.

However, as I have continued to reflect on the place of African people in the reparations debate and their entitlement or lack thereof to reparations, I have noticed that one very specific group has gone missing in this conversation: descendants of the enslaved on the African continent.

Many people in West and Central Africa have distant ancestors who were taken across the Atlantic in bondage. But what I’m referring to are those with more direct links to their enslaved ancestors.

Take the 450,000 strong population of Cabo Verde. Prior to the 1460s, the West African island was uninhabited, only to be slowly populated over the years by enslaved Africans from the mainland. This island, which continues to almost exclusively be populated by descendants of chattel slavery, has at times been referred to as “The Caribbean Of Africa” but more so due to its notoriety as a popular tropical getaway for Western tourists than its links to slavery. These links seem to have gone unnoticed by many.

Other groups that come to mind are descendants of enslaved people who were “returned”. In Britain, whenever slavery and reparations are brought up, we get the usual voices telling us that Britain has already paid its dues because it abolished the slave trade in 1807 and then spent over 50 years trying to prevent slave ships from crossing the Atlantic in an attempt to enforce the ban. Between 1807-1860, the West Africa Squadron of the Royal Navy (which included a ship lovingly named “Black Joke,” a 19th-century term for female genitalia) patrolled the waves, turning back around 1,600 slave ships and saving around 150,000 people.

While the British government dedicated time and money to this operation, with around 1,587 people losing their lives while working to save others, those who bring up this squadron as a defence against criticism about Britain’s role in slavery rarely flag that Britain had been trafficking enslaved people for centuries, and that by the mid-18th century, Britain was the foremost European power involved in the slave trade. Altogether, British merchants enslaved roughly 3.4 million people over almost 150 years.

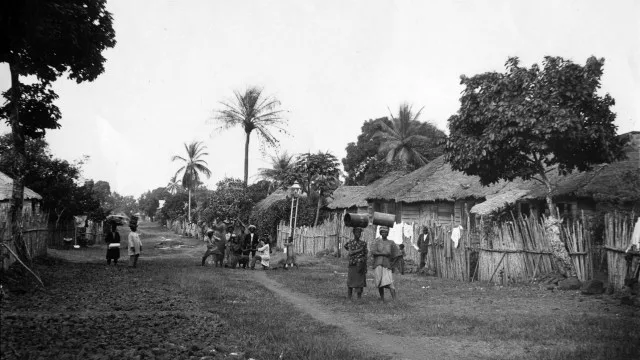

Critics also rarely remark on what became of the 150,000 who were saved. Many of these “liberated Africans” settled in Sierra Leone, which itself became a British colony in 1808 and served in part as a safe haven for formerly enslaved people.

Prior to 1808, Britain had already returned some of the formerly enslaved to Sierra Leone as part of the “Black Poor” expedition of 1787. In the 1780s, parts of London’s East End came to be populated by groups of formerly enslaved people, including a considerable amount of Black Loyalists – people who had fought on the side of the British during the American Revolution in the hopes of attaining freedom. It was proposed that these people be “repatriated” to Sierra Leone, where they would be given land and an opportunity to start over. Although many died on the journey to and upon arrival in Sierra Leone, some were able to establish lives there.

A few years later, after losing a 1795-96 conflict with the British colonial government, some 600 Jamaican maroons (groups of people who had secured their freedom from slavery by escaping to the mountains and forests) were deported to Sierra Leone.

Many of the formerly enslaved – whether they arrived because they were saved, “repatriated” or deported – now have descendants from Freetown to Kabala who are today known as Sierra Leonean Creoles. People descended from Sierra Leonean Creoles include figures like Ryan Giggs and Idris Elba. Even Afrobeat giant Fela Kuti was thought to have had a Sierra Leonean Creole (or a “Saro”, as Sierra Leonean Creoles are known in Nigeria) ancestor.

Sierra Leonean Creoles are not too dissimilar from Americo-Liberians, descendants of the formerly enslaved who came over to Liberia following its founding by the American colonisation society in 1822 as a “homeland” for African-Americans. This was despite the fact that many indigenous groups already living in Liberia did not exactly consent to this.

And Sierra Leonean Creoles and Americo-Liberians are not too dissimilar from Aguda (the Portuguese word for cotton) people, formerly enslaved people who voluntarily migrated from Brazil to West Africa as Brazil moved towards finally abolishing slavery in 1888. Their descendants include people like acclaimed British-Nigerian author Bernadine Evaristo.

Are Cabo Verdeans, Sierra Leonean Creoles, Americo-Liberians and Aguda people entitled to reparations? If so, is this on the same grounds as descendants of the enslaved who never stopped living in the Americas or on different grounds? From whom should they receive them? These are questions that will continue to go unanswered until these groups are properly considered in the global conversation on reparations. As more voices enter the conversation, and complex issues within it continue to be thoroughly unpacked, we may just see a positive resolution to the reparations debate within our lifetimes.

Seun Matiluko is a British-Nigerian journalist whose work looks at politics, race and pop culture. She is currently developing a podcast about British West African identity