- Details

- By Rhonda McBride

-

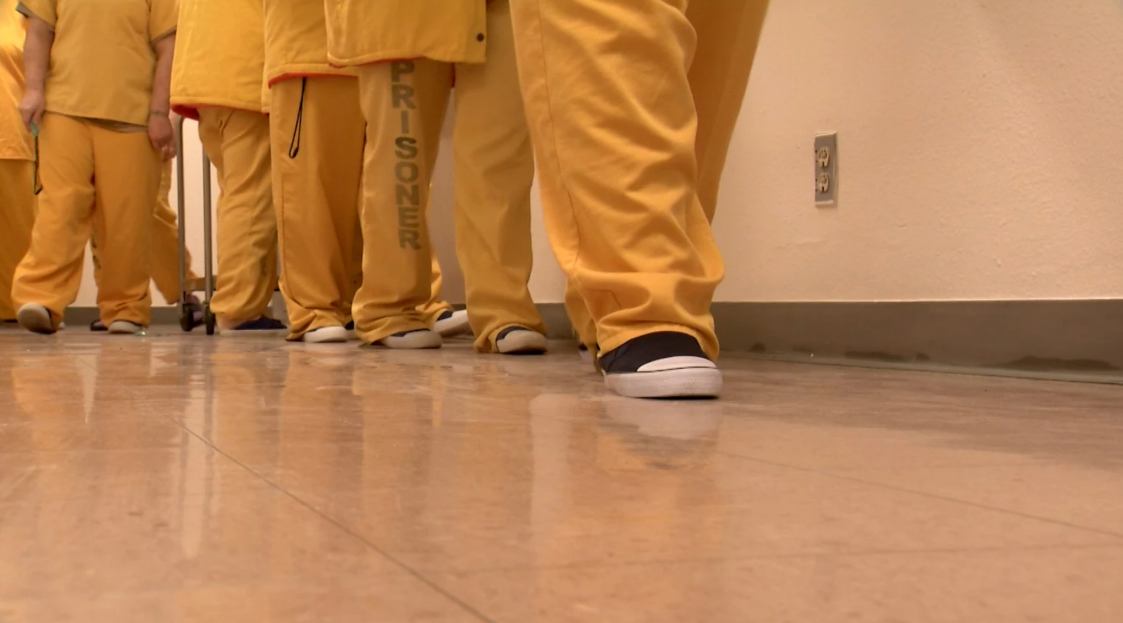

A national prison research group, which tracks inmate populations, says American Indians and Alaska Natives, next to Blacks, are vastly overrepresented in state prison systems nationwide, and Alaska tops the list.

Prison Policy Initiative, a Massachusetts-based think tank, drilled down on inmate population counts from 2021. It looked at every state and found that Alaska Natives make up 40 percent of the inmates in Alaska prisons, yet are only 15 percent of the state’s population.

The numbers also show that the total number of Native prisoners in Alaska is almost equal to those of white inmates. In the 2021 count, 4,600 people were incarcerated in Alaska prisons. Out of those, almost 1,895 were white, compared to 1,855 Natives.

Wanda Bertram, a spokeswoman for Prison Policy Initiative, says those numbers are a red flag.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by KNBA. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

“That suggests something not just out of proportion, but also deeply unjust about the criminal justice system,” Bertram said. “I think that what it says is Alaska’s criminal justice system is racist. It’s just that simple.”

But Brad Myrstol, a researcher at the University of Alaska Anchorage Justice Center, says the picture is much more complicated, because Alaska’s prison system is structured differently than most other state correctional centers.

“It’s one thing to talk about disparities and try to understand how they’re produced,” Myrstol said. “It’s quite another thing to talk about discrimination, which implies a systematic intent.”

He says, when analyzing data, he looks at what he calls the three D’s: Difference, disparities and discrimination.

Myrstol says the “difference” for Alaska lies in how its prison system is structured. Most other states, he says, house inmates in two separate institutions, prisons and local jails. But in Alaska, the two are combined into one, known as a “unified corrections system.” Alaska and five other states — Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island and Vermont — have unified systems.

In most states, unsentenced or pre-trial inmates are housed separately.

Myrstol says there is more racial disparity in this population, usually traced to poverty. He says white inmates are more likely to be able to afford bail or legal help to get out on supervised release, but Alaska Natives and other minorities don’t have those resources, so they remain incarcerated longer while awaiting sentencing. Myrstol says a backlog of court cases, created by the COVID-19 pandemic, has made the problem worse.

Myrstol says he can’t say whether Alaska’s criminal justice system is racist.

“What I will say is we see disparities throughout the criminal justice system in Alaska and elsewhere. And the reasons for those disparities are complex, but they are very important to understand,” Myrstol said. “But we have to guard against over simplistic, single-cause explanations.”

But Prison Policy Initiative says regardless of how you add up the numbers, American Indian and Alaska Native inmate populations, nationwide, are way too high, compared to overall population.

“In this country, you’re disproportionately likely to end up in prison if you’re a Native American,” Bertram said. “And that’s true, regardless of what state you’re in. It’s even more likely, even more disproportionately likely, if you’re in Alaska.”

And given Alaska’s numbers, Bertram says the key to reducing those rates is understanding the root cause of these disparities – such as looking into whether high rates of homelessness among Alaska Natives drive up their numbers in prison.

“That could mean that low level things like panhandling or sleeping on the street — or using drugs — can get you jail time, that can sometimes lead to prison time for other charges,” Bertram said. “And people who are poor are effectively railroaded into the prison system.”

Nationwide, Bertram says, Bureau of Justice incarceration rates for Alaska Natives and American Indians, as a group, have been growing at an alarming rate.

Since 2000, inmate populations in Indian Country jails climbed by 62 percent. In all other local jails, the number is even higher, at 85 percent.

As for Alaska prisons, Brad Myrstol says it’s easier to identify the disparities than it is to resolve them.

“Departments of Corrections have very little control on the inputs that they receive,” he said. “We live in a society where we seek equality under the law — and when we see disparities, it begs really important questions.”

Stand with us in championing Indigenous journalism that makes a difference. Your support matters.

Support our Indigenous-led newsroom as we shed light on critical issues, such as the painful history of Indian Boarding Schools. To date, we’ve published nearly 200 stories dedicated to this important topic, providing insights and awareness to a global audience. Our news is freely accessible to all, but its production demands resources. That’s why we’re reaching out to you this month for your generous contribution.

For those who commit to a recurring donation of $12 per month or more, or make a one-time donation of $150 or greater, we’re excited to offer you a copy of our upcoming Indian Boarding School publication. Additionally, you will be added to our Founder’s Circle. Together, we can ensure that these vital stories continue to be told, shared, and remembered.