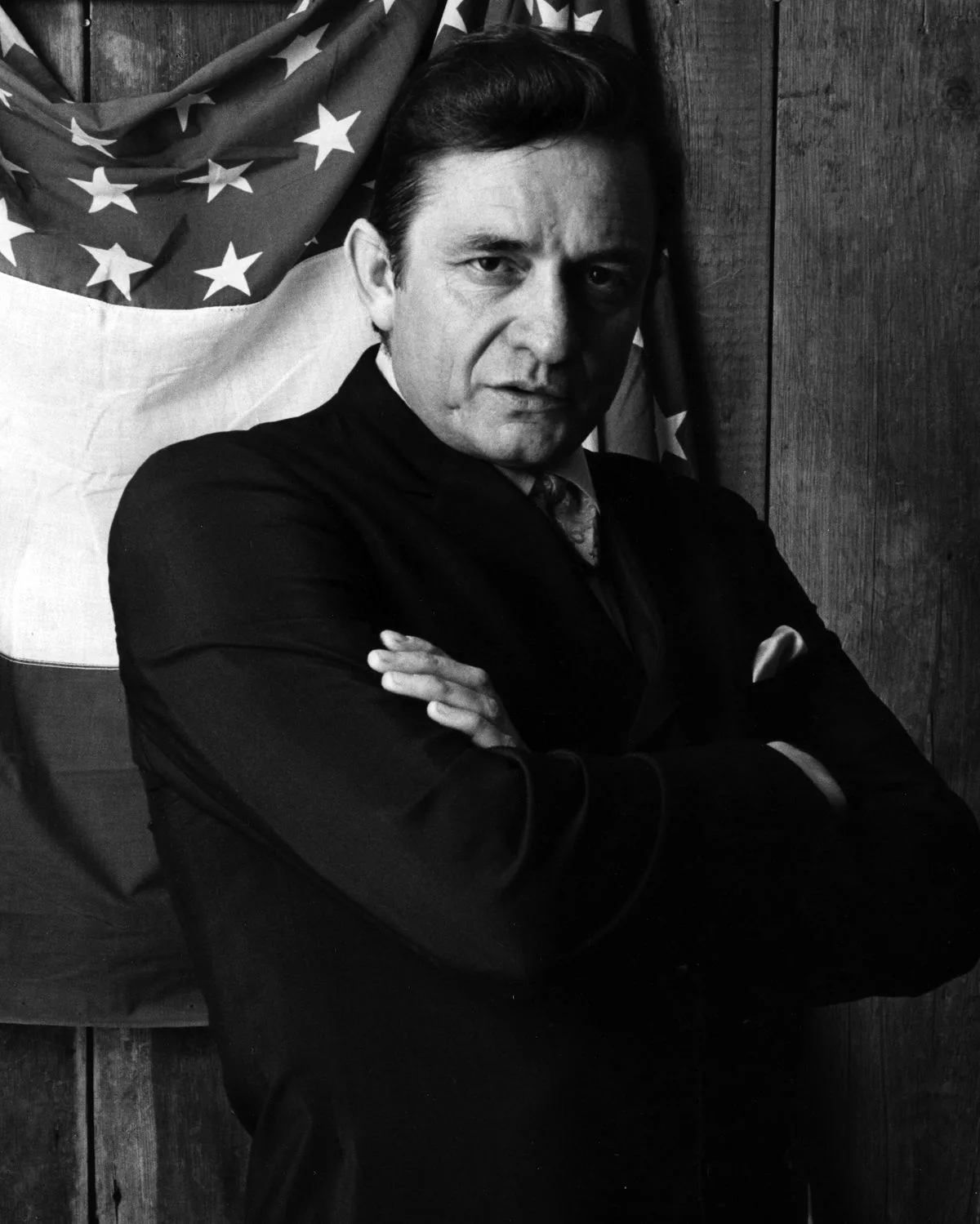

In 2004, the Republican Party met in New York to nominate the candidate for the presidential elections and, once again, chose George W. Bush. These political conventions have a social dimension, and the Tennessee delegates organized a party in the Sotheby’s showroom, where private paraphernalia belonging to Johnny Cash and his wife, June Carter, was on display to be auctioned a few days later.

News of the party and its venue got about, and a crowd of protestors came to Sotheby’s headquarters to harangue the guests. They claimed Cash was a liberal, or leftist, and hurled accusations at those present, calling them “grave robbers.” Confusion ensued among Republicans, who had never doubted that Johnny was a right-wing icon, who espoused red state views.

A brand-new book argues that both sides were wrong to claim the singer as their own. In Citizen Cash: The Political Life and Times of Johnny Cash, cultural historian Michael Stewart Foley says, “Cash, without really intending it, fashioned a new model of public citizenship, based on a politics of empathy.”

Foley describes the nuanced episodes of Cash’s turbulent life and provides its social context. Cash grew up in the Dyess colony, Arkansas, in the Old South. Foley explains that Dyess was established as a federal agricultural resettlement community in 1934, known as Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal development, which sought to provide homes and land to farmers, such as the Cashes, impoverished by the Great Depression. It was not about freebies, and Foley lays out the grievances of those New Deal settlers and their difficulties in unionizing. But despite its problems, the New Deal was better than the farmers’ previous existence and sheds light on why, by all accounts, Cash tended to vote Democrat.

Then, there are the contradictions of Cash’s military record. Despite his image as a loyal soldier, Cash, in fact, tried to avoid being drafted. After the outbreak of the Korean War, he enlisted in the Air Force, which kept him out of the trenches. With his incredible ear, he landed a safe job as a radio intercept operator in Germany, listening to Soviet transmissions to differentiate between signal from noise. The job was eight hours a day and, in his downtime, he was able to interact with local girls and form a band. Still, he never stopped supporting U.S. troops and even toured bases in Vietnam. He sang about the misfortunes of those conscripts, but he never actually criticized the war, nor did he mention the Vietnamese and Cambodians, its main victims.

The same contrariness is evident when it came to his stance on racism. While he ardently defended the rights of American Indians, he ignored the main marginalized minority, the African-Americans. There was an intellectual disconnect between his humanism and his southern roots: he identified with the Confederates, essentially champions of slavery.

One theory about Cash’s inconsistencies is that he was trying to ingratiate himself with new audiences without giving up his conservative country parochialism. But it seems that, on the contrary, he was following his impulses, even if those went against his interests. For example, as a Billy Graham fan, he was loading his Johnny Cash Show with religious content, until ABC cancelled him.

According to Foley, Cash practiced the politics of empathy. He did not think in terms of ideologies; he was moved by experiences, sympathies, and intuitions. His affinity with the American Indians probably came from the fact that he believed he had Cherokee blood, though a daughter’s DNA test proved this to be a family myth. As that beautiful line by Kris Kristofferson said, he was “a walkin’ contradiction, part truth and part fiction.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition