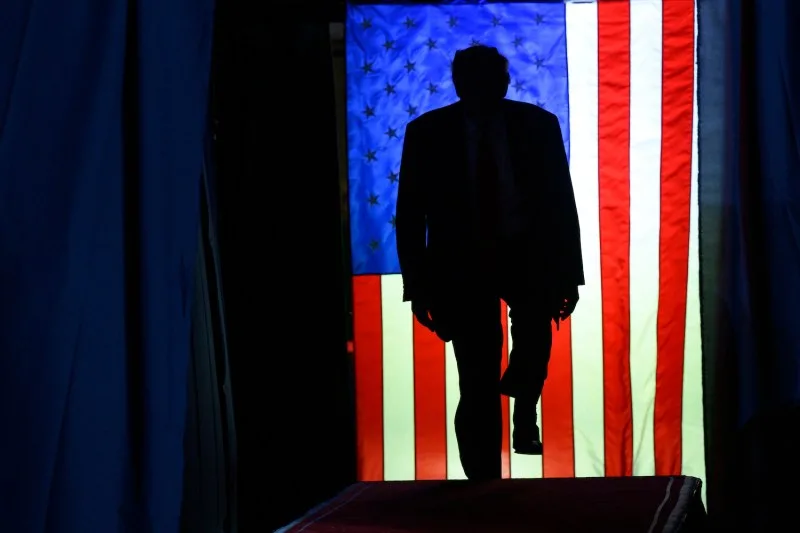

How the U.S. Created Its Own Reality

Historian Heather Cox Richardson charts the roots of 21st-century disinformation—and how American democracy began to falter.

On Dec. 25, 1991, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev resigned, marking the end of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The fall of the Soviet Union meant the end of the Cold War, and those Americans who had come to define the world as a fight between the dark forces of communism and the good forces of capitalism believed their ideology of radical individualism had triumphed. With the Soviet Union vanquished, they set out to destroy what they saw as socialist ideology at home.

On Dec. 25, 1991, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev resigned, marking the end of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The fall of the Soviet Union meant the end of the Cold War, and those Americans who had come to define the world as a fight between the dark forces of communism and the good forces of capitalism believed their ideology of radical individualism had triumphed. With the Soviet Union vanquished, they set out to destroy what they saw as socialist ideology at home.

[Subscribers-only: Watch Heather Cox Richardson discuss her book on FP Live.]

The breakup of the Soviet Union gave political operatives and the politicians in the United States for whom they worked a new, crucial tool to undermine U.S. democracy: money, and lots of it, from international authoritarians, especially those from Russia and other former republics of the Soviet Union. Politicians from the U.S. Republican Party and foreign authoritarians began to make alliances over money, influence, and plots to gain power.

This article is adapted from Democracy Awakening: Notes on the State of America by Heather Cox Richardson (Viking, 304 pp., $30, September 2023)

Since the 1980s, authoritarian governments had figured out they could score U.S. foreign aid by claiming they were standing against communists. Political consultants Charles Black, Paul Manafort, and Roger Stone, who had come together in 1980 to work on Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign, racked up clients by touting their connections to the Reagan and George H. W. Bush administrations.

They represented so many authoritarian governments—in Nigeria, Kenya, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), Equatorial Guinea, Saudi Arabia, and Somalia, among others—that a 1992 report from the Center for Public Integrity called their firm the Torturers’ Lobby. They brought under one roof lobbying and political consulting as well as public relations. Bundling these functions was groundbreaking: They would get their clients elected and then help other clients lobby them.

As oligarchs began to take over former Soviet republics, the ties between oligarchical methods and the U.S. political system grew. Oligarchs looked to park illicit money in Western democracies, where the rule of law would protect their investments, and they favored the Republicans who championed their hierarchical view of the world. For their part, Republican politicians focused on spreading capitalism rather than democracy, arguing that the two went hand in hand.

At home, Republicans set out to vanquish the liberal consensus once and for all. As anti-tax crusader Grover Norquist wrote in the Wall Street Journal: “For 40 years conservatives fought a two-front battle against statism, against the Soviet empire abroad and the American left at home. Now the Soviet Union is gone and conservatives can redeploy. And this time, the other team doesn’t have nuclear weapons.”

In the 1990s, movement conservatives—who wanted to gut the liberal state that had been in force since 1933 and rely instead on market forces—turned their firepower on those they considered insufficiently committed to free enterprise. Their enemies included traditional Republicans who agreed with Democrats that the government should regulate the economy, provide a basic social safety net, promote infrastructure, and protect civil rights.

Their first public victim was President George H. W. Bush, who had come to office from the traditional wing of the Republican Party and set out during his presidency to repair the holes cut in the country’s fabric by Reagan’s supply-side economics.

Bush was willing to raise taxes to address the $2.1 trillion debt Reagan had run up in his eight years in office. These tax hikes drew the fury of movement conservatives, who called him and other traditional Republicans “Republicans in name only,” or RINOs, arguing that they were helping to bring “socialism” to the United States. Republican lawmakers moved further right, and those openly supporting the liberal consensus disappeared from party leadership.

Their primary target, though, was Democrats, who had frustrated movement conservatives once again in 1992 by putting former Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton into the White House. James Johnson, a jurist from Arkansas who had stood fervently against the integration of Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957, called Clinton a “queer-mongering, whore-hopping adulterer; a baby-killing, draft-dodging, dope-tolerating, lying, two-faced, treasonous activist.” Surely such a man was not a legitimate president. In 1996, the Fox News Channel debuted on cable television, joining right-wing radio talk show hosts to feed the idea that their political opponents were socialists trying to destroy the country.

Clinton frustrated right-wing ideologues, not just with his domestic positions, but also because they thought he did not push U.S. ideology hard enough overseas in the wake of the Cold War. In 1997, political commentator William Kristol and scholar Robert Kagan brought together Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and other neoconservatives, or neocons, to insist that the United States should significantly increase defense spending and lead the world.

Key to their organization, called the Project for the New American Century, was the removal of Iraq’s president, Saddam Hussein, from power because they believed he was destabilizing the Middle East. Iraq had allied with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and when it invaded its smaller neighbor Kuwait in 1990, U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had convinced Bush to bring together an international coalition of 39 countries to impose sanctions on Iraq and to stop Saddam from occupying and absorbing Kuwait.

Acting under Article 51 of the United Nations charter, which permits “collective self-defense,” they did so. But after accomplishing that goal, they honored the charter and declined to topple Saddam. To the neoconservatives’ chagrin, the next president didn’t seem to get the point either: The United States must “challenge regimes hostile to our interests and values,” according to the Project for the New American Century, and “promote the cause of political and economic freedom abroad.”

Saddam was out of reach until Sept. 11, 2001, when 19 al Qaeda terrorists, inspired by Saudi exile Osama bin Laden, flew airplanes into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon outside Washington, D.C., and were on course to hit the U.S. Capitol before that plane’s passengers crashed the plane into a Pennsylvania field.

Neocons saw the attack as an opportunity to “hit” Saddam, although he had not been involved. Fifteen of the terrorists were from Saudi Arabia, two from the United Arab Emirates, one from Lebanon, and one from Egypt; they were operating out of Afghanistan, where the ruling extremist Islamic government—the Taliban—permitted al Qaeda to have a foothold.

President George W. Bush launched rocket attacks on the Taliban government, successfully overthrowing it before the end of the year. And then the administration undertook to reorder the Middle East in America’s image. In 2002, it announced the Bush doctrine, saying that Washington would preemptively strike nations suspected of planning attacks on the United States. Then in 2003, after setting up a pro-U.S. government in Afghanistan, the administration invaded Iraq.

But the Iraq War was not popular at home, and its unpopularity pushed the administration to equate supporting the Republicans with defending the nation against Islamic terrorists. That rhetorical strategy permitted them to strengthen the power of the president over Congress, most dramatically over the issue of “enhanced interrogation techniques,” more popularly known as torture, which in 2002 the administration began using against suspected terrorists.

Although the United States had traditionally considered torture illegal, the administration now argued that any limit to the president’s authority to conduct war was unconstitutional. When news of the program broke in 2004, Congress outlawed it, only to have Bush issue a signing statement rejecting any limitation on “the unitary executive branch.”

Meanwhile, the shared ideas and interests among rising global elites began to create a tangled web of money laundering, influence peddling, and antidemocratic plots that festered in foreign governments and infected the United States.

In 1996, Manafort managed the Republican National Convention, and by 2003, he and his partner, Rick Davis, were representing pro-Russia Ukrainian oligarch Viktor Yanukovych. In July 2004, U.S. journalist Paul Klebnikov was murdered in Moscow for exposing Russian government corruption; a year later, Manafort proposed working for Russian President Vladimir Putin’s government in former Soviet republics, Europe, and the United States by influencing politics, business dealings, and news coverage. In 2008, Davis was the director of Republican presidential nominee John McCain’s campaign, and McCain celebrated his 70th birthday with Davis and Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska on a Russian yacht at anchor in the Balkan country of Montenegro.

McCain was well-known for promising to stand up to Putin, and his running mate Sarah Palin’s claim that she could counter the growing power of Russia in part because “they’re our next-door neighbors, and you can actually see Russia from land here in Alaska, from an island in Alaska” became a long-running joke. But observers noted that some of McCain’s political advisors were backing the Kremlin’s interests, including Russia’s extension of control over Montenegro.

Steve Schmidt, a campaign advisor who was fiercely loyal to McCain, later explained, “There were two factions in the campaign … a pro-democracy faction and … a pro Russia faction,” the latter led by Davis. Like Manafort, Davis had a residence in New York City’s Trump Tower, owned by one of the first clients Black, Manafort, and Stone had taken on in 1980: a New York City real estate developer named Donald J. Trump.

Increasingly, Republican politicians seemed to be operating on the old hierarchical idea that some people were better than others and should direct the economy, society, and politics, and they maintained that control by advancing a false narrative for their supporters that cast their opponents as enemies of the country.

In 2004, having manufactured information meant to justify the invasion of Iraq, the Bush administration was deeply entrenched in that ideology, no matter what the facts showed. A senior advisor to Bush disdainfully told journalist Ron Suskind that people like him—Suskind—were in “the reality-based community”: They believed people could find solutions based on their observations and careful study of discernible reality.

But, the aide continued, such a worldview was obsolete. “That’s not the way the world really works anymore. … We are an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors … and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

From Democracy Awakening by Heather Cox Richardson, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Heather Cox Richardson.

Heather Cox Richardson is a professor of history at Boston College and an expert on American political and economic history. She is the author of seven books, including the award-winning How the South Won the Civil War. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Guardian, among other outlets. Her widely read newsletter, Letters from an American, synthesizes history and modern political issues. She is the co-host of the Vox Media podcast Now & Then. Twitter: @HC_Richardson

More from Foreign Policy

America Prepares for a Pacific War With China It Doesn’t Want

Embedded with U.S. forces in the Pacific, I saw the dilemmas of deterrence firsthand.

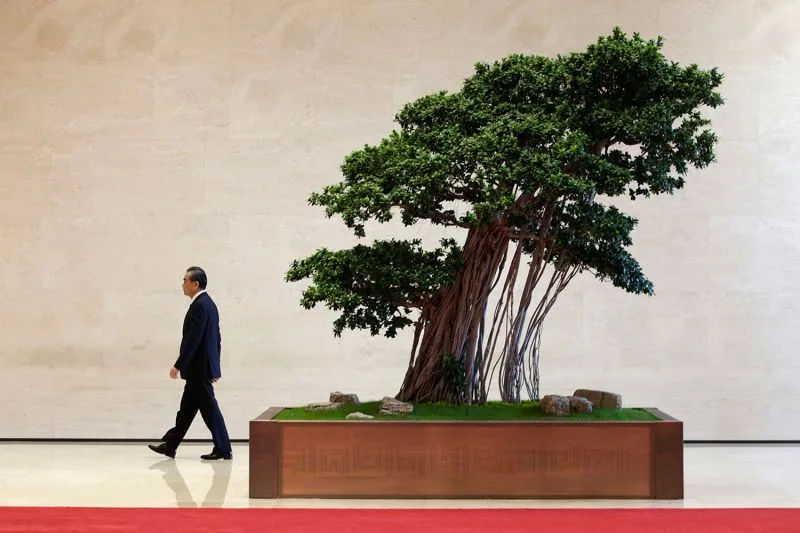

The Endless Frustration of Chinese Diplomacy

Beijing’s representatives are always scared they could be the next to vanish.

The End of America’s Middle East

The region’s four major countries have all forfeited Washington’s trust.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out