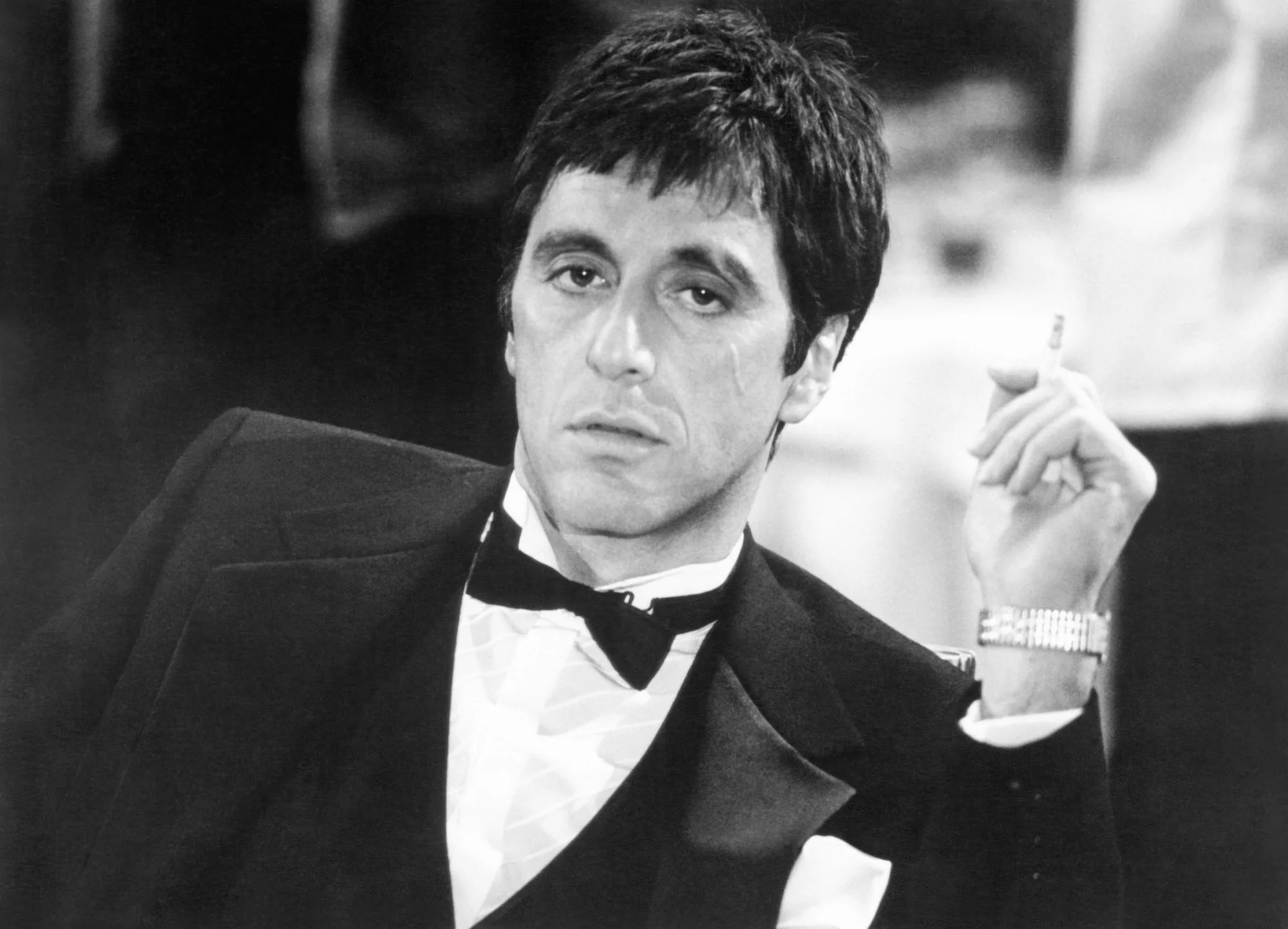

“It’s the greatest love story—that movie is emblazoned on us. It romanticizes the decadence and excess that is hip-hop,” DJ Quik says from the Zoom rectangle, holding up a photo of himself wearing a T-shirt featuring the image of one of Al Pacino’s most famous roles, Scarface’s Tony Montana.

Though Scarface centers on the rise and fall of a fictitious Cuban immigrant turned Miami cocaine kingpin—a story inspired by Al Capone, an Italian American mobster, and directed by Brian de Palma, who is also of Italian descent—it resonates with Quik, and with me. We are African Americans, born and raised on opposite sides of the country with upbringings marked by different generations. And yet we have this deep love for Italian American actors—and the country’s cinema at large—that bridges the gap between us. Quik vividly remembers when the VHS of Scarface first made its way to his California neighborhood, while I fondly recall a Christmas morning from my childhood when my mother gave me copies of the Rocky movies and the Godfather trilogy.

I grew up in South Jersey, where you could no more extract the Italian American influence from my formative years than you could separate salt from saline. Around the dinner table, my loved ones would joke about Sicily’s proximity to Africa. We’d talk, lovingly, about the seasoning in our respective cuisines, about how some southern Italians looked like us.

My mother passed down an abiding love of Pacino, Sylvester Stallone, Robert De Niro, and Joe Pesci. I’d catch her watching The Sopranos when I’d come home from school. The sense that Italians and African Americans were somehow connected felt ingrained, but I’ve recently started to think about the ways cinema reflects back to us as a group with its own history of stereotyping, marginalization, and class. When I would watch Italian Americans onscreen, I recognized that there is a white-Black binary; at the same time, there was a spectrum of whiteness and the less WASP-presenting one was (darker skin and hair, thicker accents, flamboyant clothing), the more bigotry they received.

Since the late-19th century, Italian immigrants and African Americans have lived close to one another, especially throughout cities and neighborhoods in the Northeast. “Italians were not a part of the white American imagination and social structure until later,” John Gennari, author of Flavor and Soul: Italian America at Its African American Edge, tells me. Like my own, Gennari’s mother grew up in New Jersey, which, along with New York and southern New England, he calls “the Sinatra belt.” Italian Americans and African Americans often worked alongside each other, whether in the southern fields, or further north. The two populations overlap in their migrations to the north. Ours is famously recognized as the Great Migration. “When emancipation comes, most formerly enslaved Black folk want to get away from the plantation economy,” Gennari said, “and those workers need to be replaced and southern Italian immigration has a lot to do with that.”

Recall the scene from Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever, in which John Turturro’s Paulie Carbone is perusing a newspaper when Nicholas Turturro’s Vinny demands to know what’s so important about his reading material.

It’s a striking scene, in part because of its fidelity to history. Extrajudicial killings of Italian Americans weren’t at all uncommon. In fact, the largest documented mass lynching in American history, in 1891, was of when 11 Italian Americans and Italian immigrants were accused of murdering a police chief in New Orleans. Public sentiment wasn’t in their favor, with even the mayor accusing Italians of being “idle, vicious, and worthless” and “without courage, honor, truth, pride, religion, or any quality that goes to make a good citizen.” Under Jim Crow, they weren’t classified as Black, but neither did they enjoy the protections enjoyed by whites. It followed that in both the North and South, noted Gennari, Italians would cross color lines not only to do business with African Americans, but to fraternize and have intimate relationships with them.

This history, depicted in films such as Jungle Fever and A Bronx Tale have their roots in Harlem and Belmont. In these films, Italian American men have romantic affairs with Black women amid a backdrop of racist, economic anxiety and urban sprawl within their respective neighborhoods.

Whiteness, as it relates to Italian American culture, has always been thorny. Vinny frequently uses the N-word, and oftentimes racism toward Black people was core to assimilation for white immigrant-minority groups. It’s apparent in The Sopranos, when Carmela scorns her mother for lamenting how dark Meadow’s complexion was as a baby, or when Tony vents to Dr. Melfi about how America opened the floodgates to Italian immigrants so that they could make dynastic families, such as the Carnegies and the Rockefellers, richer through their labor. Though African people were captured via slavery, their labor was just as necessary for the bolstering of American infrastructure. You see it, too, in Quentin Tarantino’s True Romance, when Dennis Hopper’s Clifford Worley notes, “Sicilians were spawned by n—–…Sicilians have Black blood pumping through their hearts.”

When waves of immigrants came to America, including Italians, Ku Klux Klan membership skyrocketed, Catholic churches were burned, while cartoons depicted Italian immigrants as being less than human. In David Roediger’s Working Towards Whiteness, he writes that one of the most common anti-Italian slurs during the 20th century, “ginny/guinea,” was originally directed toward enslaved Black people from Guinea—a stretch of the West African coastline from Sierra Leone to Benin. But with the mass migration of Italians beginning in the 1890s, the pejorative was redirected. Similar to depictions of African American men and their masculinity, stereotypes have persisted about Italian immigrant men and their propensity toward violence. Nothing captures that better than a depiction of organized crime.

Mob cinema had been around for decades. As early as 1906, silent-era shorts propagandized Italian immigrants as being excessively emotional and violence-prone. In 1906, The Black Hand is about two Italian Americans who blackmail a butcher. The characters were versions of Mustache Pete, a term used to describe a Sicilian mafioso who arrived in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. “Mustache Pete” was an insult that younger Italian Americans would direct toward their elders and “zips” were what the elders directed toward the youth before the larger population co-opted these slurs toward the entire group.

Mob movies persisted for decades, but their tone changed in the 1970s, when, between Watergate and the end of the Vietnam War, traditional American morality was being challenged. “Things are turned inside out,” says Dr. Todd Boyd, professor of cinema and media studies in the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts. “People who are thought to be legitimate and aboveboard are revealed to be quite the opposite. There’s an appetite for people who are normally looked on as criminals to be seen in a more humanistic light.”

Enter two landmark cultural touchstones of 1972: The Godfather’s Don Corleone and Super Fly’s Youngblood Priest. One Italian, the other African American, both New Yorkers who achieve status and riches in America through illegal means. Unlike the race films of prior decades, such as 1943’s Stormy Weather and 1954’s Carmen Jones—which combated the racism toward African Americans in popular culture—Blaxploitation films like Super Fly were not interested in racial uplift. The protagonists were profane-talking slicksters who had no problem talking about white hegemony or chasing someone down for money. Both The Godfather and Super Fly were contemporaneously criticized for propagating stereotypes about their respective communities, but the critics couldn’t keep them out of the canon.

“It’s the ultimate outsider sensibility,” says Boyd. “How does an outsider potentially navigate their way to the inside of American society? People find identity in these nontraditional characters who are able to expose the hypocrisy inherent to the system itself.”

The outsider sensibility that Boyd refers to in The Godfather set the precedent for Italian American films that followed its astronomical success. The outsider, or the underdog, seizes fortune and power—often through illegal means—as a way to access privileged spaces that were traditionally exclusionary to those of his ethnicity.

Take, for example, the tense scene in The Godfather II, when G. D. Spradlin’s Senator Geary justifies a demand for a larger-than-normal payment for a Nevada gaming license for Michael Corleone. “I don’t like your kind of people,” he says. “I don’t like your kind of people. I don’t like to see you come to this clean country with your oily hair, dressed up in those silk suits, trying to pass yourself off as decent Americans…I despise your masquerade, the dishonest way you pose yourself.” Both Geary and Corleone understand that this “masquerade” is Italian Americans adopting the style and comportment of WASPs in order to get a piece of the American Dream.

Kiel Adrian Scott, a millennial director of David Makes Man and The Bobby Brown Story, hones in on the arc of Michael Corleone: “People forget that Michael was the good son…He was the war hero. He was also the person who wanted to marry outside of his ethnicity. It’s the aspiring of the erasure of non-whiteness as an Italian.” To Scott, the Corleone dynasty exemplifies what happens when those like Michael buy into the American dream and what happens when they are prohibited from it. Such is the rise and eventual fall of Michael Corleone, the Ivy League–educated veteran son of working-class Italian immigrants, who tries to play by the rules, breaks him, and suffers for his choices.

Perhaps no film centers another working-class Italian male protagonist better than Rocky, released two years after Godfather II in 1976. Unlike Michael Corleone, however, the titular character talks slowly and carries a gentleness about him that others mistake for stupidity. Balboa is not a gangster—he’s not Tony Montana—but his underprivileged social status coupled with his strong, family-oriented nature has left a mark on Black audiences.

Boyd has spent an inordinate amount of time convincing people that the story of Rocky Balboa has racist, anti-Black undertones because of how Apollo Creed and Mr. T are depicted as being brash and flamboyant or sexually aggressive, respectively.

Robert Daniels, one of the foremost Black millennial film critics, can understand why Rocky resonates in spite of its flaws. When solicited for this interview, Daniels tells me that he was reminded of a specific joke from Eddie Murphy’s 1987 Raw comedy special where he spends a segment discussing the film: “Italians are funny people ’cause they act like n—–.” Like myself, Daniels also admitted that he, too, was given the Rocky box set as a child. For Daniels, who grew up on the west side of Chicago, he sees a class-solidarity element to it because unlike Apollo, who is rich and famous at the start of the movie, Rocky is still working class. But from a wider cultural touchpoint, at the time of Rocky’s release in the mid-’70s, there was an open lane for working class, underdog narratives. According to Daniels, “the end of Blaxploitation and Rocky overlap a little bit. Between the end of Black exploitation and the beginning of the Black renaissance (of TV and film) in the ’90s, there’s a solid 15 years where Rocky is the closest you’re gonna get.”

By the ’80s, American culture shifted again. Society at large was still interested in underdog stories, but the depictions were much more overt and flamboyant than its predecessors. It didn’t hurt that the American economy was doing exceptionally well—too well, perhaps, given the levels of greed and consumerism. Movies like Wall Street and Fatal Attraction depicted this era of yuppie men in corporate jobs whose morality and integrity are little or nowhere to be found.

Scarface, released in 1983, was different. Though Tony Montana and Gordon Gekko were both extremely wealthy non-WASPS, we see more of Montana’s origin story. Montana first lived in a Miami slum, whereas our first impressions of Gekko are within a swanky Manhattan neighborhood.

Initially, Scarface was neither a blockbuster nor critical success. Since then, however, the story of Tony Montana has reached an almost-mythical status—one that Boyd attributes to Black people, particularly rappers: “The film really put up when it was put out on VHS and it appealed to many rappers, particularly from the West Coast. The whole gangster element of hip-hop, which is linking the streets to the culture, a film like Scarface is very much a part of that. The film’s a cautionary tale…but I also thought one of the reasons many Black people like Scarface is because it’s biblical.”

Scarface also rose to popularity concurrent with the crack epidemic coursing through Black and Latinx neighborhoods. “The movie was a good influence on us, changing the economic drudgery and rigmarole that we were going through,” recalled Quik. “Everybody wanted to be Tony Montana.” Hip-hop legend Big Daddy Kane echoed to me a bit of Quik’s memories, but saw another factor in the reverence for Scarface: Loyalty. Montana, said Kane, “had that ‘from nothing to something’ attitude—coming from poverty to become successful because of what he learned in the streets.”

It’s that street mentality that had Black audiences across generations—from rappers like Junior M.A.F.I.A. and Jay-Z to younger artists like Chief Keef and DDG—find a kinship in Montana. It’s why Corleone and Balboa have captured our imagination across generations. By nature of their birth, they begin their lives as social outcasts just like the vast majority of African Americans. Their success by any means necessary is as much of a revenge fantasy on white Americana as it is a cautionary tale.

The Godfather serves as an umbrella for all the movies and its stars that came out from under it. The themes are ever present: loyalty, family and tradition, social marginalization, success through the exposure of the system and the subversion of it. We see these undercurrents carry on through the ’90s with films like Casino and Goodfellas—and into the 21st century with The Sopranos, where even Carmela’s name is a nod to its cinematic ancestor The Godfather.

This is particularly why Black people, irrespective of age, can have discussions about Italian American cinema. They bind us together in a cultural tapestry of our childhood, deepest desires, and angst toward the racism and classism that should have never been our own to shoulder. The game is rigged. Each ethnic group has known this since our people landed on the shores of this country either by captivity or through immigration. And unfortunately, not much has changed. Italian Americans and African Americans are still discriminated against, the American dream is still a chimera as racial wealth gaps persist, and our interpretations of “crime” and who gets “criminalized” remain hyper-focused on the behavior of non-WASPs.

It is with this reason that the Corleone family, over a half century old, is just as much of a fixture in a Black American household as Tony Soprano. They are family as we feel like family to them. In spite of the racism and tribalism that separates us, as two communities who know what it’s like to be on the outside, to be surveilled yet not seen, spoken to yet looked down upon, we want the gangster, or the working-class boxer—the underdog—to win. Because when these characters win, they mock the social hierarchies put in place to subjugate us. When they win, we are thrilled to see what is possible. If only for a moment.