Photo caption: 3D rendering of an AI robot working in a smart office. (Kittipong/Canva)

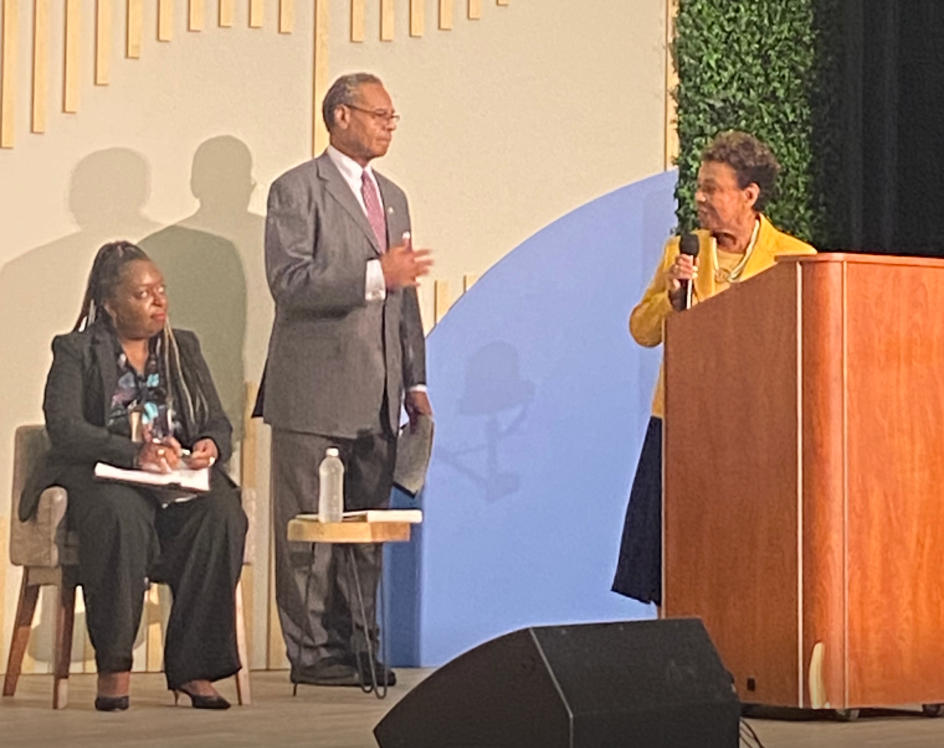

During a panel discussion at the annual Congressional Black Caucus legislative conference, Rep. Barbara Lee said AI has “No diversity, no Black lens.”

Making inroads on the artificial intelligence (AI) front has been a well-documented uphill battle to make sure the most diverse voices inform the ongoing conversation about computer systems that rely on datasets to learn patterns and make predictions.

One particular fear is that Black people will be entirely left out unless they’re involved in the process early on. But while tangible progress is being made on the aforementioned front, there is still a far way to go.

“The impact on minority communities – especially the Black community – is not considered until something goes wrong,” California Congresswoman Barbara Lee said Wednesday.

Lee sounded the alarm while speaking during a panel discussion that she was co-hosting at the Congressional Black Caucus Annual Legislative Conference in Washington, D.C. It was one of several sessions about AI planned during the week of policy conferences in the nation’s capital about issues impacting African Americans and the global Black community, accentuating the importance of both the topic and the moment.

“AI bias and discrimination are a direct result of a lack of diversity of the teams creating the models,” Lee continued before emphasizing: “No diversity, no Black lens.”

She described the plight of inclusion in AI as “another front on the civil rights spectrum,” a sentiment expressed by panelists who similarly underscored the urgency to level the playing field before it’s too late.

Moderated by Kimberly Bryant of Black Girls Code fame, the discussion – entitled “Friend or Foe How AI Impacts The Black Community” – also addressed the importance of investing in Black tech companies and expanding Black communities’ footprints in the tech space.

However, the overarching theme of how AI impacts Black folks was paramount as experts in the field offered their thoughts on how to move forward.

Myaisha Hayes, the Campaign Strategies Director at MediaJustice, pointed to efforts by tech companies to dodge accountability for how AI impacts the Black community.

“Part of the reason why we’re not also making progress is because a lot of these tech companies kind of push this narrative that AI and technology are just too complicated to explain now,” Hayes said before explaining that’s just “a talking point to shield them from calls for accountability.”

Pointing to her previous experience as the National Organizer on Criminal Justice & Technology at MediaJustice, Hayes stressed the absence of transparency when it comes to AI and how it can adversely affect Black people.

One particular example, Hayes said, was in the criminal justice system where AI models are being used to assess so-called pre-trial risks and make predictions about whether people will appear in court. Hayes said the data points informing the algorithms, like zip codes and age, are coming from the legal system and supposed to be an indicator of crime.

“They’re actually an indication of who is the most policed in our country,” Hayes said. “And so it’s absolutely possible to build transparency, but that’s a choice that [tech companies] aren’t making.”

Hayes said it’s important to stop conceding to that point, but sometimes that’s easier said than done because so many Black people don’t come from tech backgrounds or have expertise in AI.

“So when tech companies say, ‘Oh, this stuff is too complicated to explain,’ we tend to believe them,” Hayes added, explaining that those corporations often exist in an environment where they get to play by their open rules and don’t feel any responsibility to comply with legal requirements and ignore public criticism.

Hayes is right.

AI systems heavily rely on vast datasets to learn patterns and make predictions. Unfortunately, historical data is often plagued with biases and has elements of systemic racism baked within. They also require the help of humans, who can inherently insert their own biases into AI algorithms and programming.

If the data used to train AI algorithms disproportionately represents negative stereotypes or discriminatory practices, the resulting models can perpetuate and amplify those biases. This is dangerous because it can create the perfect breeding ground for anti-Blackness, leading to unfair treatment and discrimination against Black individuals in various domains, such as criminal justice, employment and lending.

The history of AI and its entanglement with anti-Blackness reveals the urgent need for critical examination, transparency, and ethical considerations within the development and deployment of AI systems. Addressing biases and ensuring equitable outcomes are crucial steps toward building a future where technology works to dismantle, rather than reinforce systemic discrimination.

Missouri Congressman Rev. Emanuel Cleaver, II, who co-hosted the panel discussion with Rep. Lee, called AI technology “almost limitless” and said “we don’t know” where it will end up.

“If we’re not pushing it or involved in it, we will get run over by it,” Cleaver, 78, warned while using an anecdote about the iPhone’s autocorrect feature trying to predict what he would type in a text message to his granddaughter.

Cleaver said that the truth about AI extends to the financial sector, too.

“We have to be in on it because also when you start talking about using different forms of wealth to do your banking,” Cleaver continued. “AI is making decisions about mortgages to figure out who can get one.”

So what is the solution moving forward? The panel discussion only lasted 90 minutes, which wasn’t nearly enough time to put an action plan into effect. But local resources are key to informing Black communities about AI and what to do next as tech companies increasingly resign supreme in society.

“So much of the knowledge that we know about AI right now is actually coming a lot from grassroots communities that are pulling together their capacity of resources to work with researchers to make this technology more accessible and more transparent to our communities,” Hayes said.

This article originally appeared on NewsOne.