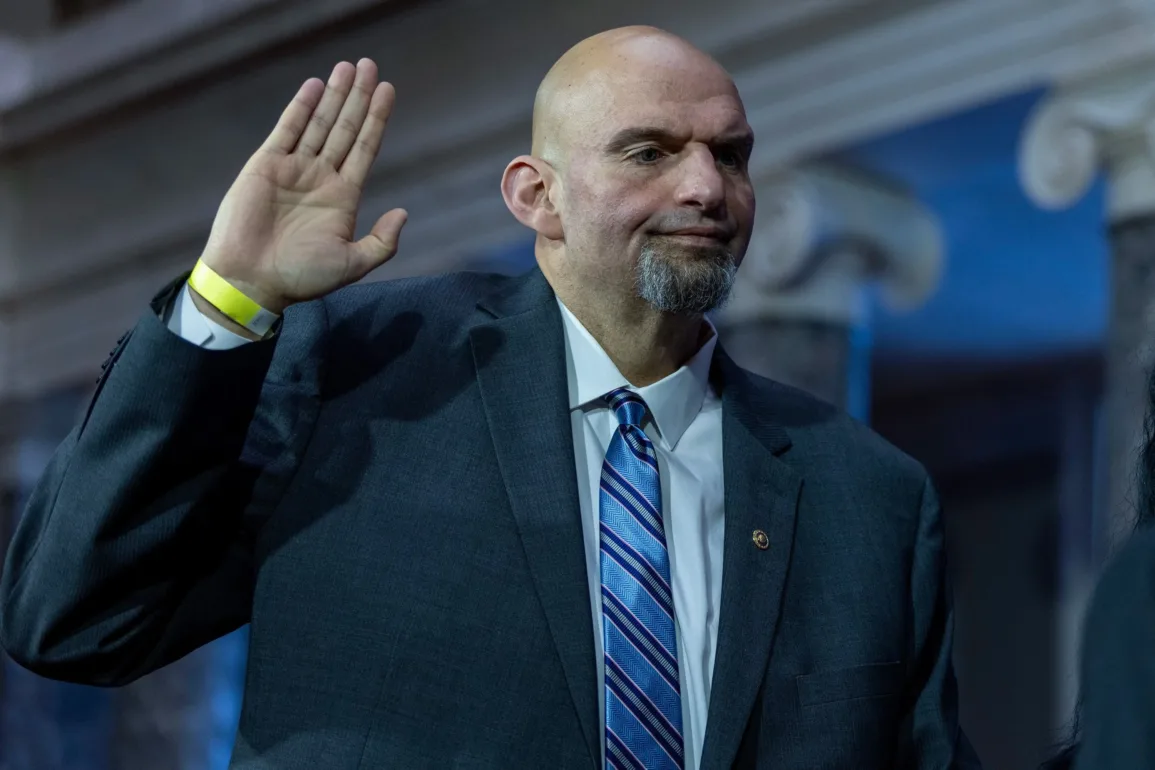

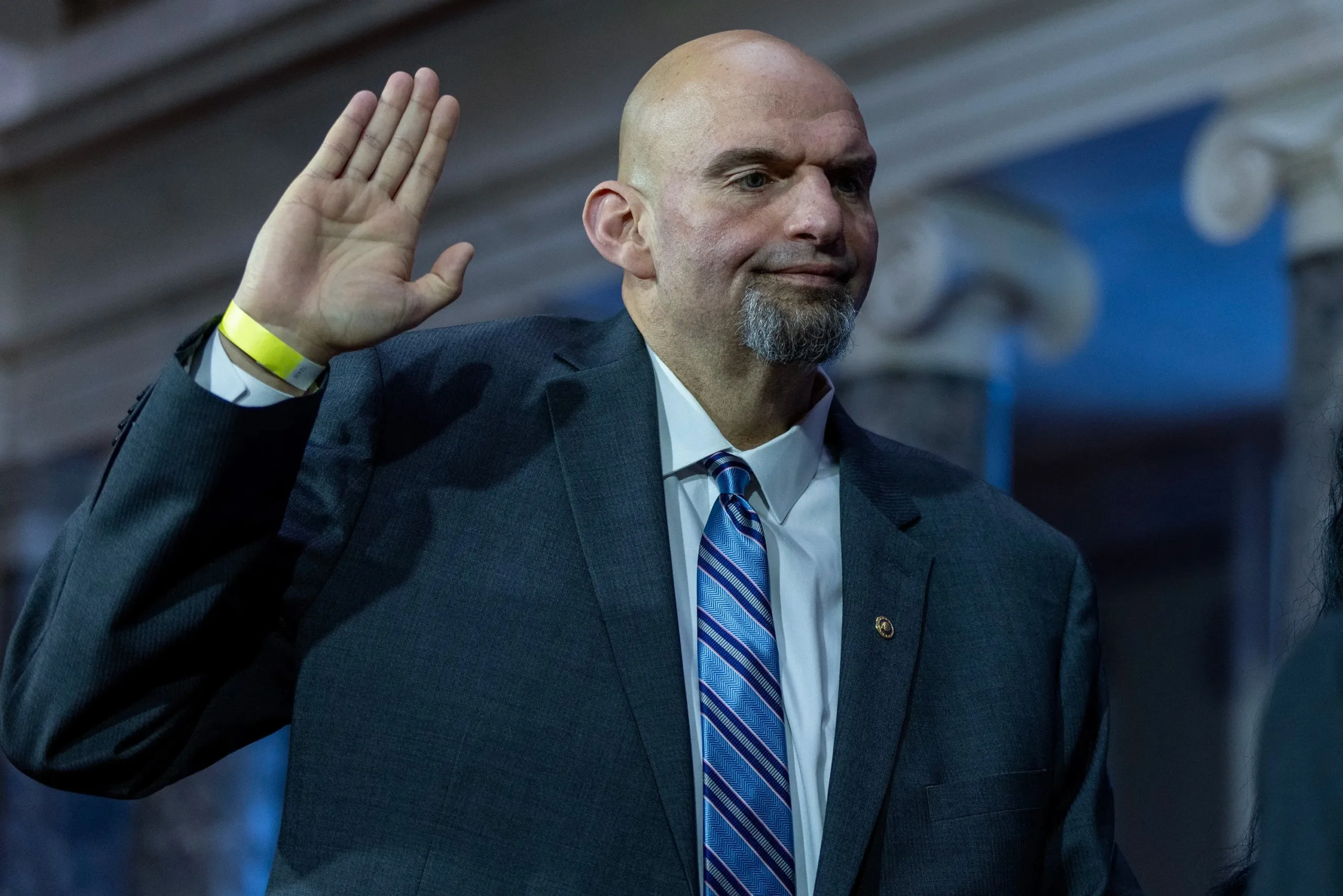

I’m no arbiter of good taste, and I think it’s safe to say that neither is Sen. John Fetterman. In fact, I’d hazard a guess and say we’re both pretty big fans of bad taste.

He inexplicably loves Sheetz, I righteously love Wawa. He enjoys trolling his haters online, I enjoy squeezing as many terrible puns into stories as possible. He dresses like it’s summer and winter simultaneously, I shop at Ross Dress for Less.

So I was happy to see Fetterman campaign for his Senate seat last year in his trademark Carhartt hoodie and shorts, the standard outfit people in Pennsylvania have known him to govern in for years (an outfit which is standard — and thus relatable — in many parts of Pennsylvania).

If Fetterman would have put on a three-piece suit and crisscrossed the state talking to Pennsylvanians in their jeans and jerseys about the everyday issues facing them, it wouldn’t have come off as genuine. He might as well have brought a crudité plate.

But after he was inaugurated in a suit and tie, I assumed it would become his standard attire in the Capitol, not because that’s who he is, but because that’s what senators do.

It’s always seemed to me that no matter who you are when you go into politics, you inevitably change in order to play the game, or, just to stay in it. But after he was treated for clinical depression earlier this year — and spoke openly about it — Fetterman has worn his hoodie-and-shorts combo around the Capitol more and more (though when in the chamber, he’s worn a suit).

Fetterman has refused to play the Senate’s sartorial game and, as a result, instead of the system changing him, he may have helped changed the system.

Beginning Monday, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D., N.Y.) directed the chamber’s sergeant-at-arms to not enforce an informal dress code that required senators to wear business attire in the chamber.

While Schumer hasn’t said Fetterman inspired the change, the rest of the country has. Conservative talk show hosts and politicians have given Fetterman hell, calling the rule change a “dumbing down” of standards and “disgraceful.”

In classic Fetterman fashion, he’s given them hell right back.

“I guess to Fox News, wearing a hoodie is more of a scandal than grabbing the hog during a live musical or showing ding-a-ling pics in a public hearing, which are two actual things House Republicans have done lately,” Fetterman wrote to those on his campaign email list.

(Further proof he’s a fan of bad taste and loves trolling haters.)

It’s not just Congress

While Fetterman may have helped precipitate the dress code change, it’s unlikely he’s the only reason for it. Richard Thompson Ford, a professor of law at Stanford Law School and the author of Dress Code: How the Laws of Fashion Made History, said “a lot of things were pointing in this direction.”

“Dress codes have been getting relaxed everywhere. In a sense, Congress is following a trend that’s already taken off in business, banking, law, and all over the place,” he said.

The relaxation of professional dress codes began in Silicon Valley and accelerated during the COVID-19 lockdown, Ford said. A greater diversity of Congressional members is another factor likely driving the move, he said, noting that in 2017, women in Congress protested justto be able to wear professional dresses and blouses without sleeves.

Fetterman has cultivated an image as someone who’s not a typical politician and his clothing signifies that, Ford said.

“I imagine he feels if he put on a blue suit and tie like everyone else in Washington now that he’s been elected, people will think he’ll turn into a typical beltway politician,” he said.

Clothing has always been political and Pennsylvania statesmen bucking fashion norms to appear more relatable to the people they serve is nothing new, according to Ford.

“Ben Franklin quit wearing a powdered wig as a statement of solidarity with the average person rather than putting on airs as an aristocrat,” he said. “It’s continued to this day.”

Coded dress codes

Historically, work place dress codes existed to make sure people convey an image their employer wants, but sometimes they’re used to subtly exclude the “wrong kind of person” too, by sending a message that if you’re not comfortable wearing a certain type of clothing, you don’t belong here, Ford said.

“Dress codes serve some valid purposes, but they also serve some purposes we’d feel uncomfortable with if stated openly,” he said.

So is the old adage that was drilled into many of us, “Don’t dress for the job you have, dress for the job you want,” no longer true?

“It’s still very much true, it’s just that the dress codes are changing… and to be successful in most fields you’re going to need to dress like a successful person in that field,” Ford said.

But politicians are different because their job is to impress voters, not a boss or their peers.

“They’re more like a celebrity creating an image than a typical employee who needs to impress the boss,” Ford said. “These politicians know their constituents, so even though it may not be popular with people nationwide, it’s certainly working for John Fetterman so he has no reason to change.”

Fetterman’s refusal to change has led to a change in the system, and in a system that often rebuffs change, that’s a good thing. It’s a reminder that change is not impossible, even in government, and that sometimes we can effectuate it just by insisting on being who we are.

That said, I can’t help but wonder if a person of color or a woman had worn Fetterman’s attire as a senator, if it would have led to the same results.

“I think that for a woman or a person of color defining the rules is riskier and the implications that might be drawn are likely to be different,” Ford said. “A hoodie and baggie shorts on an African-American person, for instance, I find it very hard to imagine it would work in the way it has for John Fetterman.”