Maternal deaths nationwide more than doubled from 1999 to 2019, according to a new study in The Journal of the American Medical Association. The research also showed death rates are especially high for Black and American Indian/Alaska Native moms.

Overall, the number of maternal deaths rose from 505 in 1999 to 1,210 in 2019. Researchers looked at mothers ages 10 to 54 who were currently or recently pregnant, and calculated how many mothers died per 100,000 live births.

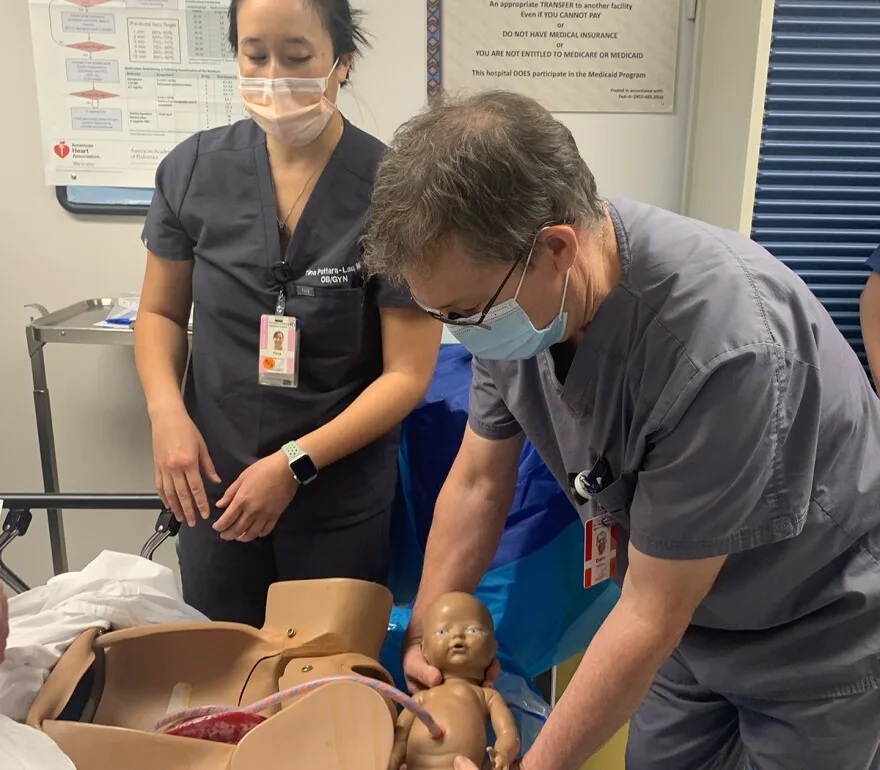

“This has been something that we’ve seen over time,” said Tina Pattara-Lau, the maternal child health specialist for the Indian Health Service. “I’ve seen challenges on a day-to-day basis that contribute to that increased risk.”

Black and American Indian/Alaska Native mothers had the highest death rates. The rate for Black moms rose from 26.7 to 55.4 deaths per 100,000 over the 20-year period. The American Indian/Alaska Native maternal death rate saw the greatest increase over that span, rising from 14 to 49.2 deaths.

For American Indian/Alaska Native mothers, the five states with the largest percentage increases in death rates were Florida, Kansas, Illinois, Rhode Island and Wisconsin – none of which are in the Mountain West. Nevertheless, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming were among the states with the highest overall maternal death rates for American Indian and Alaska Native women.

Arizona and Montana had some of the higher rates of Black maternal deaths, joining states like Georgia, Mississippi and New York.

Authors of the study concluded “persistent disparities” exist for these groups of women, and prevention efforts during the study period had a “limited impact.”

Pattara-Lau said many factors play into these maternal death numbers, like a lack of hospitals in rural areas, long drives to get medical care and increases in mental health problems over the years in these demographic groups. Historical trauma and systemic racism can further exacerbate these issues—and even last generations, she added.

Indian Health Service

For instance, a patient who has used substances might be worried about how doctors will respond to that usage due to a mistrust of the health care system. Many states enforce mandatory reporting to employers, which creates fear in patients that they might lose their job. But if the patient has had an exposure to syphilis – which can be easily detected early in the pregnancy and treated with penicillin – but does not tell a doctor, it could cause complications.

“We’ve made that diagnosis when it’s too late because, again, of the mistrust that exists in some of the state policies around mandatory reporting,” Pattara-Lau said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported last year that more than 80% of pregnancy-related deaths were preventable. For American Indian and Alaska Native mothers, that percentage is even higher, at 93%.

Pattara-Lau said this begs some very important questions about how medical professionals are supporting mothers in prenatal care.

“What we should all aim for if we truly want to achieve equitable access to health care for all is a model of cultural safety,” she said. “This looks at not only historical trauma, but how that plays into how health care systems are set up, whether they’re accessible for the people who need them (and) whether they’re led by the people who they serve.”

She advocated for a better buildout of health care in rural communities through the use of telehealth and other resources. This comes after the American Hospital Association found 136 rural hospitals closed their doors from 2010 to 2021 – with 19 closures occurring in 2020 alone.

Pattara-Lau also said more doctors could build trust with patients by involving community members and cultural practices in the birthing process.

“We found, both anecdotally as a provider but then also across the board, that patients often respond and are more engaged to medical care when they have an advocate, whether that’s a birth support worker or a community member,” she said. “I’ve had the honor to work with (the Native community). It’s very family-centered, and relying on your elders, and leaning on your aunties and relatives is really important.”

Mothers seeking support can look to websites like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Hear Her campaign, which offers information about maternal warning signs geared specifically for tribal communities, or The Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal Mental Health Hotline, which offers confidential support 24/7 in many languages, including some tribal languages.

“If we don’t start caring now about the outcomes of Black and Indigenous persons, we will see the effects of that long term, not only on their communities and their societies, but on our society as a whole,” Pattara-Lau said.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Nevada Public Radio, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, KUNC in Colorado and KANW in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2023 KUNC. To see more, visit KUNC. 9(MDA5MzE4MDYzMDEzMzQyNTcyNTY4NDMyNw001))

9(MDA5MzE4MDYzMDEzMzQyNTcyNTY4NDMyNw001))