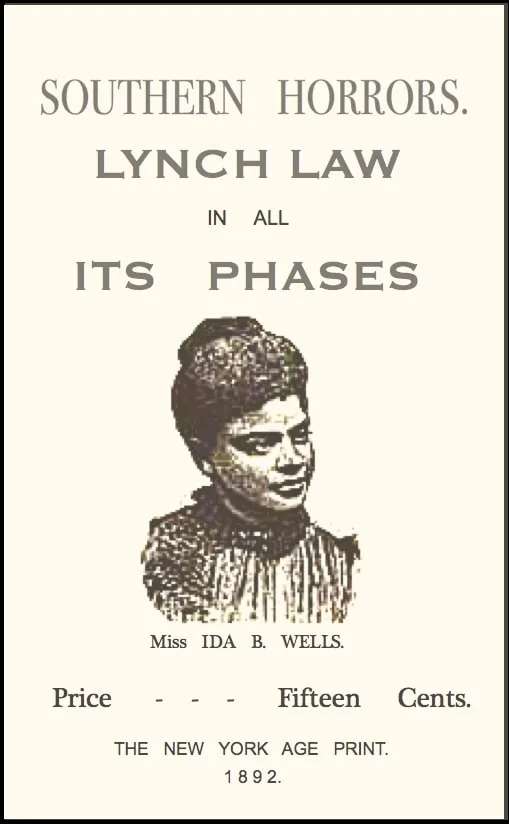

In August 1894 it was rumored that Ida B. Wells, the celebrated black journalist, anti-lynching crusader and suffragist was coming to Santa Cruz! Her news articles and booklets were hard-hitting. Her research in the Jim Crow South was unprecedented and courageous, facing credible death threats. Yet “Iron Ida” (as she might be called) stood steadfast against the mob. She’d just returned from speaking tours of Great Britain and would next visit the California Midwinter Fair in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, then come to Santa Cruz to visit family and give an anti-lynching lecture.

William and Fanny Tipton had brought their family to Santa Cruz in 1889 and moved to River Street near Kron’s Tannery in 1892. The Tipton household included their children, and two of Ida’s younger sisters, Annie (17) and Lillian (18), as well as black Civil War veteran, 48-year-old Henry Barnett. Fanny Tipton was Ida’s aunt, whom she stayed with in Memphis in 1881, plus Fanny’s daughter, Ida Wells II, age 8 at the time. But Ida Wells II was not able to greet her namesake cousin, being just across the San Lorenzo River from them, so family members loaded the wagon to go and visit her, picking some garden flowers as a gift, then going south to cross the Water Street Bridge.

Ida Wells II and Ida B. Well’s sister Annie went to Santa Cruz High School. Ida II was described as “intelligent and promising.” However, she had a condition that made her light-headed, and then pass out. Unable to complete her schooling, she returned home to convalesce, until at last she recovered. She went to work for Pacific Avenue jeweler Edward N. Radke, as a domestic at his house at 18 Lincoln St. Ida’s Ben Lomond friend visited her for a few days at her River Street home. Afterward, Ida took her friend to the train station, then the horse obediently returned the wagon to their home, but when her father came out to meet her, he found the carriage was riderless. Some men at Kron’s Tannery discovered Ida II’s body in the street and tried to revive her, but she was dead, having passed out and fallen onto the street. Ida B. Wells decorated her cousin’s grave in the Odd Fellows Cemetery.

Yet far happier was the news about Annie Wells, who in 1894 was only the third African American to graduate from Santa Cruz High School, and Annie would become a lecturer and newspaper editor like her famous sister. Ida B. Wells chose the Santa Cruz Congregational Church for her speaking engagement (recalled Phil Reader to Lisa Johnson), which included a Chinese Congregational Association. The church was located at “Churchside,” a cluster of churches at the corner of Lincoln and Center streets (now the Boys and Girls Club). Rev. Mahlon Willett and Mayor Robert Effey made introductory comments, including Wells’ biographical details. Henry Barnett was proud to hear he and Ida were both born in Holly Springs, Mississippi.

Ida’s childhood

Ida’s mixed-race father, James Wells, was owned by his white father in Tippah County, Mississippi, but in 1858 James was hired out as a carpenter’s apprentice to architect Spires Boling in Holly Springs.

Construction work was skilled labor in which James excelled, building the Boling House in 1860, and living in a shack behind it. James helped build many grand mansions and courthouses designed by Boling.

James took as his mate Boling’s gourmet cook, Lizzie Warrenton, who gave birth to Ida B. Wells July 15, 1862, during the Civil War. Ida was owned by Boling for only four months, until Gen. Ulysses S. Grant made Holly Springs his military headquarters, ending slavery in the Union-controlled areas in November 1862. Grant’s headquarters were in the Boling-designed/James Wells-built mansion of Harvey Walter, president of the Mississippi Central Railroad, and an anti-secession Southerner. James ran his own carpentry business on the Boling farm, finding plenty of work in the rebuilding effort after the war, and signed up to vote as a Lincoln Republican. Boling urged James to vote for the Southern Democrat, but James refused and moved his carpentry business across the street from the Boling place.

With marriage forbidden to slaves, James and Lizzie got married in the Methodist Church to legitimize their union. They would have eight children, with Ida the eldest. The wife of his owner/father asked James to come for a visit, but he refused ever to return. On Nov. 24, 1866, the Freedman’s Aid Society of the Methodist Church built Shaw College (now Rust College), a liberal arts institute for Black students. The college was three blocks north of the Wells home, teaching both James and Lizzie to read, and James became a college trustee. James and Lizzie impressed the importance of education on their children and enrolled 14-year-old Ida in Rust College in 1876. In 1878, Ida had a disagreement with the president of the college, and was expelled. Having disappointed her parents, Ida went to visit the farm of her grandmother, Peggy Cheers Wells.

Then Ida learned she could not return home. The Yellow Fever Epidemic, lasting from July to November 1878, had a quarantine blockade within 30 miles of the river, that was enforced by shotguns. In a short time, Yellow Fever took both of Ida’s parents, and her baby brother Stanley. Having lost brother Eddie previously to spinal meningitis, the six remaining children were orphans. “Iron Ida” refused to let her family be put up for adoption. At 16, Ida lied about her age to work as a teacher in rural school and Sunday school, while relatives helped babysit. Sister Eugenia was just a year younger than Ida but died in 1881 at age 18. So Ida secured her brothers’ jobs as apprentice carpenters in Holly Springs, then took sisters Lillian and Annie to live with her in Memphis with their aunt, Fanny Butler Wells (later Fanny Tipton). Here she met her 8-year-old namesake, Ida Wells II.

Ida B. Wells taught school, then during the summer attended Fisk University in Nashville. Ida had taken the train to visit Holly Springs from Memphis for the past two years. Then in 1884, a conductor demanded Ida give up her seat to a white woman, but Ida refused, holding up her first-class ticket, and was kicked off the train. She sued the railroad and won, but the judgment was reversed in federal court. Two years later, Ida wrote an article criticizing unequal funding for black schools and lost her teaching job. So she turned full-time to journalism. She bought a share in the “Memphis Free Speech,” becoming the first female co-owner and editor of a black newspaper. Her pen name was “Iola,” Greek for violet, symbolizing loyalty to truth, and a safeguard against evil.

Ida’s cause

In 1892, three friends in the grocery business were lynched by a white mob while in police custody, sparking a national outcry. Ida investigated the incident and concluded a white-owned grocer sought to eliminate the competition. In her newspaper exposé she proposed boycotting the grocer or leaving Memphis to safer towns. The boycott and Black exodus made such an impact on white businesses, the mob came to lynch Wells, destroying her newspaper office, but she was out of town. She couldn’t return to Memphis, so she moved to Chicago, conducting in-depth research on lynchings throughout the South, which she published in pamphlets and newspaper articles that became popular across the country. These mob killings were being termed “Lynch Law,” implying they were spontaneous justice for Black crimes, usually alleged as raping a white woman or murdering a white man. Ida’s investigation found in two-thirds of the lynchings no crime was ever named, and concluded lynchings were a terrorist campaign to solidify white control in the South. Lynching was most common in states that leased prisoners as a source of cheap labor, a system that incentivized false arrest of Black people and was a thinly disguised form of slavery.

In 1893, Ida was invited to lecture on lynchings in Scotland, Ireland and England. She returned in 1894 to tour as a correspondent for the Daily Inter Ocean, a mostly white-run Chicago newspaper. Ida told the Edinburgh Ladies’ Emancipation Society, that the close of the Civil War did not end the persecution of Black people in the South, having documented the lynching of 1,000 Black men and women in the past decade. Some Americans were embarrassed that she was airing the nation’s dirty laundry abroad, but she was seen as a hero in Santa Cruz. A letter reached her in England, supporting her anti-lynching crusade, and inviting her to speak in Santa Cruz. The letter dated May 10, 1894, appeared in British papers around the world, signed by 60 leading Santa Cruzans, including a Supreme Court judge, sheriff, mayor, postmaster, teachers, pastors, newspaper editors, doctors, bankers, lawyers, merchants and the local state senator. (South Wales Daily News, May 30, 1894).

Ida was upset that the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893 had a Women’s Building to show the advancement of women, but did not provide an African-American Building to show the progress of formerly enslaved people freed in the nation’s costliest war in bloodshed. Instead, the Chicago fair made primitives the only representation of Black people. And the 1894 California Midwinter Exposition in Golden Gate Park presented the Gold Rush without ethnic representation, leaving out the Chinese and Black prospectors, and slaves brought to dig gold for their Southern masters. On Aug. 4, 1894, Ida gave a talk at Bethel A.M.E. Church in San Francisco, introduced by Thomas Fortune, president of the Afro-American League, on which William Tipton sat as the Santa Cruz representative. These civil rights groups kept folding as they lost focus on what mattered, and Ida attempted to reestablish the group, but conflict between an activist approach, and an uncontroversial approach doomed each group. At last in 1909, Ida helped to establish the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People).

Santa Cruz found her speech vital, and hoped she would return someday. Meanwhile, Ida was also devoted to the women’s suffrage movement, being a close friend of Susan B. Anthony (who had relatives in Santa Cruz). Had she not died in 1906, Anthony wouldn’t have permitted what happened in a Washington, D.C., suffrage parade. It was March 3, 1913, the eve of President Wilson’s inauguration. Before the parade, Ida was told they had to avoid the offense of Black people and white people marching together. She was thus removed from the Illinois delegation and told to march at the tail-end of the parade. Instead, Ida joined the spectators on the sidelines. When the Illinois delegation approached, Ida stepped in front of them, and for the rest of the march, she led them all! “Iron Ida” marches on!