Richmond, Virginia is in a period of reckoning with its past. The foundational practices and behaviors of the United States began here with wars, fires, and riots reshaping the city landscape and in turn the national policies that followed. One such moment has been the decommissioning of confederate symbolism. Since the 2015 mass shooting at AME Church in Charleston, Richmond administrators have been challenged to remove flags, statues, and names associated with the confederacy and its legacy. The Monument Ave Commission held its first meeting in 2017 to generate public comment on what to do with the statues. It was a rowdy crowd of polarizing opinions and failed attempts to find a recontextualized middle ground. History would come to the surface during the George Floyd Protests. It would take the 2020 uprising to begin this process in earnest after residents tore down statues erected in dedication to colonial history and the civil war. The failure of the commission to remove a single statue in three years was achieved by protesters in a few months. This moment asked city inhabitants to make a choice of continuing to uphold revisionist civil war history or to reimage Richmond as a place for the struggle for freedom and diversity. The city administrators’ choice to remove the remaining confederate statues and rebranding of schools and street signs elicits a progression for the latter. There have been a few detractors who wish for Richmond to remain a city enveloped in a revisionist idea of the antebellum South. Some went as far as suing the State of Virginia for taking down statues as unconstitutional with at least two of the plaintiffs being direct descendents of those who helped construct Monument Ave.

In the wake of these decisions a nonprofit emerged “to preserve Virginia’s history and craft the most prosperous future for all of its citizens”. The Virginia Council’s claim to “preserve” history for “all of its citizens” appears disingenuous when you see, for what history and which citizens they want to promote. Early this year on February 24, 2023 the Virginia Council, funded by the Common Sense Society, hosted a far-right British personality, Douglas Murray, at the Jefferson Hotel. Murray is known for his vitriolic views on immigration, Islam, feminism, and identity politics. The discussion at the Jefferson centered on “uncancelling history” which non-ironically seeks to cancel education projects he perceives as attacking the founding fathers. He describes programs like the 1619 project as propaganda, “An attempt to turn the story of America into a story of original sin, slavery and much more”. He goes on to support a straw man argument that critiquing the founding fathers is equated to a hatred of America itself. Murray’s claim of history being “turned on its head” negates how the fictionalized stories of America created a mythologized view of United States history and reflects what in history they want to remain as status quo. He ignores the real grotesque violence that founded this country by misplacing a desire for historical accuracy as a threat to America’s stability. He essentializes the history of the founders as inherently a net positive despite the aspects of how slavery and exploitation factored into its creation. Even further he ignores the abolitionist history that existed in parallel to the dominant white land owning elites, and who did actually fight for the freedom of all American residents.

At the end of this month the Virginia Council will hold another event for a far-right personality whose criticism of statue removal, under the guise of free speech, is known to influence white nationalist violence. Andy Ngo would become the darling of Tucker Carlson and Neo-nazi accelerationist groups with his reporting of the 2020 protest in the city of Portland, OR. His attempts to livestream and expose identities of protesters would eventually lead to a physical altercation leaving him with a black eye and covered in a milkshake. He exploited this moment to gain media attention through a fictitious narrative of protesters as a nationally coordinated organization. His promotion of hit lists against protestors and his conspiracies that mass shooters who espouse white nationalist views are instead leftists undercover would influence the neo-nazi group Attomwafen, that has been linked to 5 murders in the U.S., to attack alleged anti fascist protesters. This meme’d into existence the phrase “Andy Ngo is a threat to our communities and provides kill lists to Atomwaffen”. Andy’s brief rise in the media quickly fell after undercover footage showed him collaborating with Proud Boys. He requested they act as his security during protests in exchange for positive coverage of their “Patriot Prayer” rallies. What makes Andy a dangerous grifter is his promotion of far-right ideology under the guise of being an independent journalist. This misrepresentation of himself and Black Lives Matter protests has put him in the spotlight of right wing media as well as putting people’s lives at risk. We should then ask ourselves why is the Commonwealth Club promoting and allowing right wing terror enthusiasts to speak in their building?

Any long term Richmonder will recognize certain names that are synonymous with the city’s geography. Tredegar Iron works, Maymont, Bryan Park, Valentine Museum, Mayo Island, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Virginia Museum of History, Richmond Symphony Orchestra, Scott’s Addition, Johnston Willis Hospital, St. Joseph’s Villa, Miller and Rhoads, Lewis Ginter Botanical Gardens, Monument Avenue, Richmond Times Dispatch, WRVA radio, Richmond Stove Works, and numerous historic mansions of the Crenshaw, Branch, and Scott houses. What links these places together is a private men’s club that has been in secretive operation since the late 19th century.

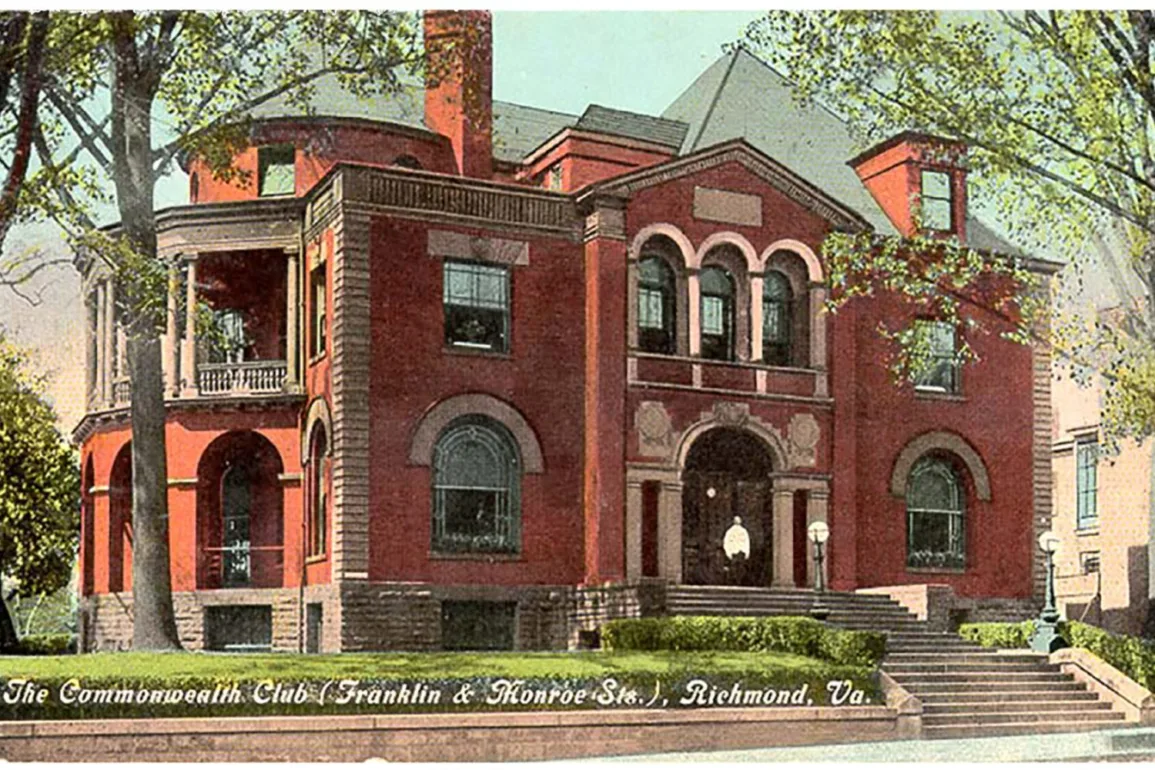

The Commonwealth Club was founded in 1890 by wealthy former Confederate soldiers and wealthy Confederate sympathizers. The stated goal of the club was “that it reflect credit upon the city and do honor to its members.” According to a History of the Commonwealth Club published in 1987, the club is meant to evoke the “style and mien of the Old South.” At least half of the Richmonders present for the founding meeting were veteran Confederate soldiers, the rest being prominent wealthy Richmonders wishing to be in “convivial fraternity” with these former Confederate soldiers. In the Richmond Times, which was owned by founding member Joseph Bryan, it was reported “…there has never been a meeting of men of social and representative characters that ever topped the one held last night at Belvidere Hall… the ardent feeling evidenced, ensured the success of the club. It will have an appropriate name and a determined following. It will be a Richmond and Virginia institution and in the future will be heard from.” The original name was the Lee Club after Robert E. Lee, CSA. This name was shortly rejected due to its association with their friendly rival the Westmoreland Club, which was named after Lee’s home county. Despite losing the claim to the Lee name, the club holds their annual meeting each year on the Friday closest to Lee’s birthday, January 19th. The property the club occupies at 401 W Franklin St. was owned by Confederates dating back at least to the Civil War, specifically George Palmer, who was almost arrested during reconstruction for flying a Confederate flag on the property.

The Westmoreland Club was formed in 1877, by nine Confederate officers in the home of a former Confederate general. The clubs enjoyed a friendly rivalry and tried to merge in 1921 but were prohibited by the Virginia Supreme Court. They successfully merged in 1937 in the aftermath of the Great Depression. The extensive art collection that had been owned by the Westmoreland Club was transferred to the Commonwealth Club, the most famous of which is The Battle of the Crater, which is a Civil War Scene displayed in the Cocktail Lounge Parlor. There is also an oil painting of Lee in the boardroom which members toast regularly.

The founding meeting on January 6, 1890 was called by James Dooley, CSA. He is known for being the former owner of Maymont and with his wife, Sallie Dooley, founded St. Joseph’s Villa. She also wrote a Lost Cause treatise, “Dem Good Ole Times”, valorizing the antebellum South from the perspective and dialect of an enslaved black woman. The first president elected of the Club was Alfred T. Harris Jr., a tobacconist whose mansion at 518 W. Franklin St. has been replaced with an apartment building. The first vice president and second president was Joseph Bryan, CSA. Born on a plantation, the son of wealthy planters, he left from studying at the University of Virginia to join the Confederate Army. After the end of the Civil War, he returned to UVA and studied law. Bryan was outspoken in his promotion of fulfilling the Confederate dream to build an independent Southern economy ruled by capitalist elites and secured by state sovereignty under traditional Christian authority. According to his obituary he was ““Richmond’s foremost capitalist” and “a symbol of the Southern Industrialist of his era.” In 1887, he purchased the Richmond Times newspaper. Then In 1896, he acquired the Manchester Evening Leader and merged the two. Those papers then merged with other Richmond papers to become the Richmond Times Dispatch. He would also own a company that mass produced locomotives, was a vestryman of Emmanuel Episcopal Church for 36 years, sat on the Board of Visitors at UVA, and served as President of the Virginia Historical Society, among other civic associations. He died of heart failure at his mansion “Laburnum” and was buried in his Confederate uniform with his coffin draped in a Confederate flag. His family donated land for Joseph Bryan Park and the Richmond Memorial Hospital, which later became Memorial Regional Hospital .

The majority of the founding members were former Confederate soldiers. They include Edmund Trowbridge Dana Myers CSA, William Lawrence Royall CSA, James D. Patton CSA (House of Delegates), John P. Branch CSA (Pres. Merchants National Bank), Peter Helms Mayo CSA, Archer Anderson CSA (co-owner of Tredegar Ironworks), Joseph R. Anderson CSA (co-owner of Tredegar Ironworks), Thomas Bolling CSA, and John Henry Montague CSA. Other notable founding members include: Tazewell Ellett, Aston Starke, Levin Joynes, Frederic W. Scott (of VCU’s Scott House), Dr. George Benjamin Johnston (of Johnston Willis Hospital), Charles E. Bolling, Wyndham R. Meredith, Blythe Branch (Founder and president of the Richmond Symphony Orchestra 1933 and founder and president of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts 1934), Thomas Nelson Page (main architect of the Lost Cause).

At the time this history was published, in 1977, the president of the Commonwealth Club was Henry C. Spaulding. He worked for State Planters Bank as a trust officer then served as a stockbroker and senior executive vice president of Scott and Stringfellow for 23 years and finally, as a managing director of Lowe, Brockenbrough & Co. before his retirement in 2000. He served on the boards of Episcopal High School and Hampden-Sydney, where he was a trustee emeritus at the time of his death. He was also a former trustee of St. Catherine’s School, a board member of the Westminster-Canterbury Foundation, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Foundation, The Valentine Museum, The Library of Virginia Foundation, and a member of St. James’s Episcopal Church.

Prior to the inception of the Commonwealth Club its members were intimately involved in constructing a revisionist historical view of the Civil War, or as they called it the Lost Cause. In 1885 the governor and nephew of Robert E. Lee, Fitzhugh Lee, began a campaign to erect the Lee monument. John Mitchell Jr, African American city council member and owner of The Planet, a Black newspaper, chastised the project and its creators , “Most of them were at a table, either on top or under it, when the war was going on.” and that the project was honoring a “legacy of treason and blood”. By 1887 the city was gerrymandered so that no Black city council member could be elected. The project moved forward with Confederate veteran Archer Anderson, co-owner Tredegar Ironworks and member of the Lee Monument Association, dedicating “the Lee Monument not as a memory to the Confederacy, but as a testament to ‘personal honor,’ ‘patriotic hope and cheer,’ and an ‘ideal leader.’” The construction of Monument Ave was a symbol of reclamation for an antebellum South still ruled by white elites. According to the 1977 Commonwealth Club history, post reconstruction left the state “demoralized. Well-meaning fanatics, Republican partisans, a group of businessmen in the industrial areas of the Union, and unreconstructed unionists who still believed the southerners were unregenated (sic) rebels, imposed upon the south a government by a people of a race utterly unprepared for such responsibility. The revolution in politics forced upon a conquered people by a group of carpetbagger strangers who taught the negro that it was their duty and privilege to keep their former master in subjection. The element in suffrage that caused the mischief was not removed until the constitutional convention met in Richmond on June 12, 1902… amended the article dealing with suffrage, so as to eliminate the negro as a group voter, without denying literate and responsible negro citizens the ballot privilege.”

The 1896 Supreme Court’s upholding of Jim Crow laws as constitutional cleared the path for strategic removal of black political leadership. By 1948, Richmond city government switched to a council-appointed mayoral system that further entrenched elite control. Descendants of the founding members of the Commonwealth Club would serve as mayors of Richmond including during the tumultuous interstate 95 construction. Thomas Bryan, grandson of Joseph Bryan, served as mayor from 1954-1956 when construction began. Shortly followed by A. Scott Anderson, a descendant of the Anderson brothers, who served as mayor from 1958-1960. The debate over the placement of the interstate was “Jim Crow by asphalt” with city administrators under the influence of the Harry F. Byrd machine, who was a lifetime Commonwealth Club and KKK member, and in its “massive resistance” campaign against integration they opted to destroy a bustling Shockoe Bottom neighborhood and pave over african american burial grounds instead of interfering with the bucolic white suburbs. Richmond’s unabated destruction of historical buildings and spaces in the late 20th century is further telling of what history the city administrators wanted to maintain and what legacies they viewed as best forgotten.

Prominent public servant members of the Commonwealth Club include US Supreme Court Justice Lewis F. Powell, Sen. Harry F. Byrd Jr., Gov. John M. Dalton, Gov. Mills E Godwin Jr., Gov. George Allen, Clement F. Haynsworth Chief Justice of the 4th US Circuit Court of Appeals, and many others who met underneath paintings honoring the Confederacy. Those discussions would fund the segregationist Jim Crow laws, the white supremacy of the Byrd Machine, and the Virginia Way that dictated industrial development throughout Virginia. Its members cling to their past as First Families of Virginia descending off of the Mayflower, and it is this legacy that excludes families who have come after. The club didn’t allow Jewish members until the late 70’s and the first black member joined in 1988. When Governor George Allen was questioned for accepting a lifetime membership to a club that has a history of promoting discrimination he claimed,“As long as they don’t I’ll join”. Adding that he has no problem with the club not allowing women membership. Allen’s 1993 campaign for Governor featured a confederate flag displayed in his log cabin and appearing at all white academies formed in response to school integration. Ten years later he would use a racial slur against a journalist spurring a list of professors, colleagues, and women claiming Allen had used racial slurs throughout the 1970’s and 80’s. L. Douglas Wilder, while serving as the only black member of the Virginia Senate, was denied entry for a meeting in 1978 and had called the Commonwealth Club, “a racist club, a retreat from the world where social gains are being made”. Behind closed doors prominent business members, such as Jim Ukrop and Massie Valentine, who own banks, railroads, tobacco, construction companies, law firms, and investment firms have mingled with legislatures to influence control over society. The hosting of Forum Clubs and public affairs luncheon have brought in former General William Westmoreland, former VCU President Eugene Trani, former UVA President John Casteen, and former Virginia Military Institute president Josiah Bunting to name a few. Today the “Virginia Way” lives on with Governor Glenn Youngkin whose campaign focus against critical race theory and his desire for full political control places him squarely in the halls of the Commonwealth Club, if he hasn’t already been.

Richmond’s modern geography has been shaped by these reactionary forces who have wanted to preserve a mythology of the Confederate South. The latest iteration comes from the Virginia Council’s promotion of historical preservation, but what underlies “preserving tradition” is an all too familiar dynamic of racist revisionism. The Virginia Council formed in 2021 in response to statue removal that they perceived as a threat to Richmond’s historic legacy. Founded by John Reid, a radio personality on WRVA which was founded in 1925 by tobacco mogul and former Commonwealth Club president Pleasant L. Reed, the board consists of a former Dominion Energy executive, the former head of a christian school, executives of Common Sense Society, and former members of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. The primary funding for Virginia Council comes from the Common Sense Society whose leadership board is stacked with former members of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation and the Heritage Foundation. CSS Chairman Thomas Peterffy is a billionaire stock broker that has given over $2 million to Glenn Youngkin’s PAC for upcoming November Virginia elections. The chairman emeritus of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation is Edwin J. Feulner who is also the founder and president of the Heritage Foundation, known as a pass-through organization for Koch Brothers dark money.

The Commonwealth Club’s promotion of Andy Ngo through a Koch Brothers funded organization serves as a current example of the reactionary ideology behind this private men’s club. They continue to exert influence on our politics and society through its generational wealth and descendants who own large amounts of property and reside on various civic boards. If Richmond residents wish to escape this cycle of reactionary violence we must divulge who belongs to these institutions. We must disavow their racist legacy through disowning the names of these institutions, and instead encourage a comprehensive view of the past to celebrate the untold stories of liberation. We must further divest our city of this legacy money from reactionary institutions, and redirect it into funding community focused projects that build affordable housing and a meaningful economy. To reflect a new direction for Richmond, we must claim land by renaming spaces for ourselves, change the name of Bryan Park, and remove the descendants of inherited wealth from its boards. The perpetuation of an elitist tradition in Richmond allows the legacy of Confederate Christian white supremacy to remain intact. If we wish to evolve the city culture then we must redress the past. They should heed advice from their religious leader Robert E. Lee, “…not to keep open the sores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife.”