Ceremony memorializes lynching of Black teen George Bush from the Boone County jail 134 years ago.

From 1865 to 1950, thousands of lynchings occurred throughout the country. At least 68 lynchings of Black people were documented in Missouri.

Two of those crimes — “the most public and violent form of racial terrorism“ — happened in Columbia, said Annabelle Simmons, a member of the Community Remembrance Project of Boone County, and a speaker at the Thursday, September 7, ceremony to commemorate the September 7, 1889, lynching of Black teen George Bush from the Boone County Courthouse and jail.

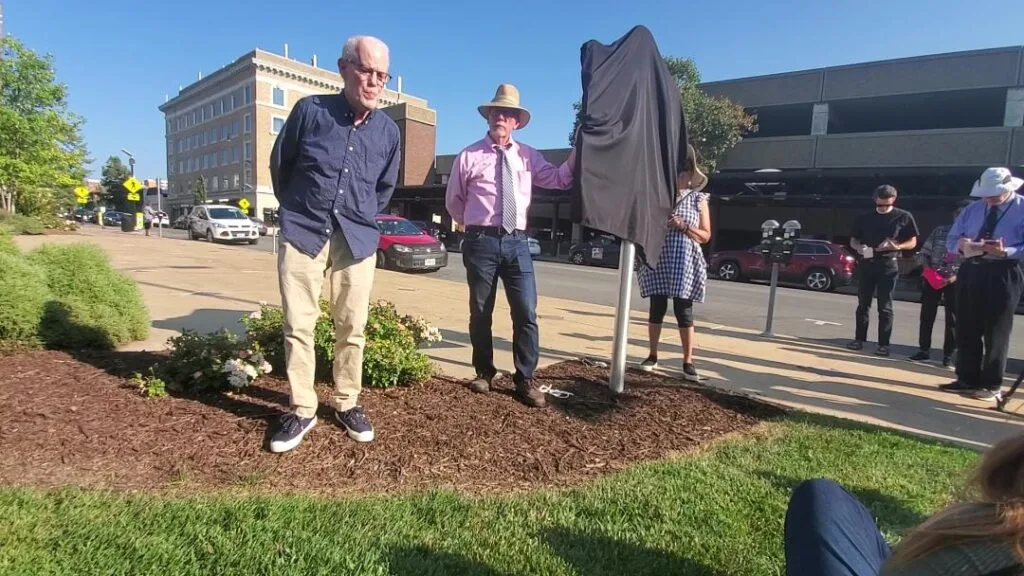

A crowd of about 60 people attended last week’s event at the Boone County Courthouse Plaza, listening from the shaded areas on the grounds as speakers somberly recounted the past and looked to the future. The crowd quietly walked from the plaza to the front of the courthouse for the unveiling of the 25th marker on Columbia’s African-American Heritage Trail — a marker that commemorates one of the darkest moments in Boone County and Columbia history.

Ward 4 City Council member Nick Foster read the account of Bush’s lynching.

On September 6, 1889, covered wagons filled with vigilantes gathered at the local fairgrounds and headed for the courthouse and jail, where Bush was being held for trial on the accusation that he “mistreated” a white teen girl. By around 2 a.m. on September 7, George Bush was dead, hanging from a second story window. The lynching was carried out by “good citizens of Boone County,” according to a note sent to the Columbia Herald newspaper.

They went on to warn that anyone who faced similar accusations as George Bush and anyone who exposed the mob members’ identities would “receive the same punishment.”

George Bush’s murderers were never identified. The coroner determined that the teen died as a result of hanging “by persons unknown.” No one was ever prosecuted.

Last week’s gathering included Kesley Spottsville, secretary of the Black Archives of Mid-America in Kansas City. Her keynote remarks paid respect to Bush’s life and memory, and took direct aim at “anti-woke legislation and anti-CRT backlash.” In some ways, she said, some things haven’t changed in 134 years. (Read her entire speech here.)

“So during these terror lynchings, we know that white children were brought to these spectacles to ‘learn’ about their false superiority as white people, that they had power over Black people, so much so that they could kill them without punishment,” Spottsville said. “What did George Bush himself understand, about being a Black boy in Columbia, Missouri? He more than likely had been taught that he was ‘kill-able’ — either directly or indirectly.”

Citing the research and writings of Kimberle Crenshaw, a pioneer in critical thought and the development of critical race theory, Spottsville added, “Our kill-ability is an enduring feature of Black life.”

Later, in front of the veiled marker, Bradford Boyd-Kennedy, a member of the Remembrance Project of Boone County, reminisced about his own teen years and how he sometimes acted impulsively without regard for the consequences. He compared that experience to what Bush might have been feeling 134 years ago.

“He was experiencing intense terror and probably remorse or regret,” Boyd-Kennedy said.

Spottsville momentarily halted the ceremony.

“I don’t believe he had any reason to regret anything,” she said. “Often times we know these were lies against” Black people who were going to be lynched. “We want to make sure we consecrate him correctly.”

Boyd-Kennedy apologized for the misunderstanding, adding that he was not passing judgment on Bush. “He is not to be blamed in any way,” he said.

Boyd-Kennedy emphasized the instructions in the “white caps” supremacist group’s note that Bush’s killers pinned to his lifeless body.

“’Don’t cut this down,’” he repeated. “Not ‘him.’ Just ‘this.’ Not a human person. A representative of a hated group. Don’t cut this down until 7 a.m.”

One side of the marker details the murder of George Bush. The other summarizes the history of lynchings in the U.S.

Jennifer Harris, senior project manager for the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, said it is important to memorialize those lynchings and other atrocities.

“It is essential for recovering from a history of racial injustice,” Harris said.

Spottsville is a founding member of the Community Remembrance Project of Missouri, which helped advocate for placing the memorial marker. In 2021, the Community Remembrance Project of Boone County dedicated a marker for James T. Scott, who was lynched in Columbia in 1923.

Spottsville said that those who oppose teaching about racial injustice and inequity — “Black poverty is passed down, just like white wealth is,” she said — are a threat to everyone.

“If these factions have their way, we would not be gathered here today to recognize George Bush,” Spottsville added.

She emphasized her belief that “systemic racism” continues to perpetuate white supremacy. She called on listeners to be “first responders for racial justice.”

“I am convinced that each one of us can make positive impact within our circles of influence, at our places of employment, at our schools and within our families,” Spottsville said. “Our charge is to organize and challenge lawmakers to demand that historical truth be taught in schools — not lies like ‘Black people benefitted from slavery.’”

Boone County Presiding Commissioner Kip Kendrick said he wasn’t aware of the George Bush lynching until attending a ceremony at the courthouse last year.

“I liked to believe I knew about our history,” he said, calling the county government’s role in Bush’s death “saddening and despicable.” He said that having the memorial on the courthouse grounds is a valuable history lesson and a reminder of “the work we still have to do.”

Ward 3 City Council member Roy Lovelady said the city’s recent investment in creating a position to oversee diversity, equity, and inclusion at City Hall is an indication of the city’s commitment to address systemic racism.

Lovelady briefly highlighted the effort to establish The Shops at Sharp End, a hub for retail startups — including minority-owned businesses — to grow their businesses. The business incubator at 109 E. Walnut St. is a partnership among Central Missouri Community Action, the Downtown Community Improvement District, and the Regional Economic Development Inc. (REDI). The location is names after the once-prominent Black business district — the Sharp End — that saw its demise as a result of so-called urban renewal in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Lovelady labeled urban renewal as “government sanctioned displacement” of minority businesses and residents.

The ceremony was organized by the Community Remembrance Project of Boone County (CRP-BC) in cooperation with the Sharp End Heritage Committee and the Boone County Commission. CRP-BC is affiliated with the Equal Justice Initiative of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, and is also affiliated with the Community Remembrance Project of Missouri (CRP-MO).

A replica of the Boone County memorial will be at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama.