Harm City: Third in a series about environmental justice and climate adaptation in Baltimore’s neighborhoods.

Laurel Peltier fumed and half-muttered an expletive as she pondered the case of Teresa McFadden, 58, a Black woman who stood perplexed on the other side of the reception desk at Cares, a nonprofit helping low-income families meet their food and housing needs.

McFadden, behind on her bills, was on the verge of getting her electricity cut off, and, in addition to not knowing what to do, had just lost her job.

Bright sunlight flooded the charity’s office nestled inside the single-storied Community Hub building of the Govans Ecumenical Development Corporation in north Baltimore’s Govans neighborhood.

The air conditioning cooled the beige-colored reception area, with a white, chest-high reception desk next to the front door, which beeped every time someone walked in.

Peltier, with specs sitting close to the tip of her nose, fixed her gaze on the pile of papers McFadden had put down on the desk.

She calls herself an energy justice advocate in a state where deregulated energy retailers, also known as “third-party suppliers,” have cost mostly low-income consumers more than $1 billion in utility overpayments since 2014, by one estimate.

For Peltier, volunteering here at Cares on Wednesdays, helping people like McFadden find the means to pay off their outstanding bills and avoid getting their power cut off has been her routine for the past seven years.

But it isn’t all she’s been doing, as lawmakers in Annapolis have come to realize.

A steady inflow of walk-ins kept Peltier on her feet behind the counter. “The pastor at my church said that you pray with your feet,” she said, juggling paperwork and newcomers waiting in line. Faith, Peltier felt, guided her commitment to community service — a way to pay back the blessings she had come to enjoy in life.

Originally from Newport, California, her mother a nurse and father a pari-mutuel clerk, Peltier graduated from University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business with a degree in business administration and worked as consumer brand manager for multinational companies, including Pepsi, for 12 years. Then she met her husband, a Philadelphia native. “And he goes, ‘Where do you want to live?’ And I said, ‘Baltimore,’” having fallen in love with the city during visits to her college roommate’s home there. She and her husband moved to the city in 1995.

She has since raised three boys. Now, she spends 30 hours a week working on energy justice, here at Cares one day a week, and as the head of a coalition of advocates working to reduce electric rates.

“I play pickleball, walk my dogs, and enjoy myself because my three kids are older, and having three kids is a lot of work. And the weird thing is, I’m a complete energy nerd. I love energy. I can’t even explain it,” she said.

McFadden sat with her legs crossed on one of the ash-colored arm chairs separated by coffee tables along the lobby walls. Clutching a stack of papers in her right hand—among them her energy bills and a cut-off notice—she wore a blank stare as if contemplating the unknown.

“When I looked at her bill, it made my blood boil,” Peltier said of McFadden’s case. “It looks like she’s been paying her bills. The real reason she got a turn-off notice is that her account is on a third-party supplier called IDT, charging her a much higher rate. And she was completely unaware of it,” she said.

In an emailed response, a spokesperson for IDT Energy said that the company does not promise lower rates than the local utility because it offers different products such as renewable or green electricity for which customers voluntarily elect to pay more in order to have a positive impact on the environment. The spokesperson said that sales representatives are instructed not to guarantee savings to customers nor to promise anything other than what is stated in customer contracts. “All utilities and retail energy suppliers experience occasional complaints. When those complaints come to our attention, we work diligently to resolve the issues swiftly,” he added.

Exploiting Deregulation

In 1999, Maryland fully deregulated its energy market after enacting the Electric Customer Choice and Competition Act, also known as “retail choice.” It allows the retailers, or third-party suppliers, to purchase energy from the wholesale market and sell it to businesses and residents at a different rate for profit, on the theory that such competition will drive down rates.

Instead, energy advocates like Peltier and some state legislators have long maintained that an unsupervised deregulated energy market opened the door to deceitful bait-and-switch practices by retail suppliers who preyed on low-income people. Often, they would hook customers on low introductory rates, then increase them, sometimes massively, if a payment was missed. Through another common practice called “slamming,” sales representatives often use customers’ utility account numbers to take over their accounts without their consent.

Proponents of retail choice argue that the state has not done enough to unlock the full potential of a competitive marketplace.

A 2021 report by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, a Washington D.C.-based think tank, found Baltimore to be particularly energy-burdened, with 25 percent of low-income residents spending more than 21.7 percent of their 2017 income on energy. Half of the city’s income-challenged residents spent more than 10.5 percent of their earnings on energy, the report said, which was the highest median spending behind only Birmingham, Alabama.

High energy burdens for low-income families are not just a matter of scant earnings, the report found. Minority groups are commonly clustered in multi-generational households, the report said, consuming greater energy because of leaky insulation, cheap construction or old appliances. Such homes can use 50 percent more energy per square foot than more energy efficient but costlier ones.

A big part of the problem, Peltier said, is that a regulation known as “purchase of receivables,” which the Maryland Public Service Commission approved in 2010, shifted the risk of nonpayment away from third-party suppliers to the utilities from which they purchased the power. This guaranteed that the retailers would be paid by the utilities even when their customers defaulted, and it gave the energy retailers great incentive to charge higher rates, she explained.

In June, the Maryland Energy Advocates Coalition, headed by Peltier, petitioned the commission to revisit the regulation and argued that it was partially to blame for predatory pricing. Acting on the petition, the PSC expanded the public comments to also include “other potential energy retail market reforms that, if implemented, should enhance the benefits of retail choice to consumers in Maryland.”

That’s a win, Peltier said.

More than 120 companies are now operating across Maryland, selling gas, electricity or both to commercial and residential customers. But a number of studies and state lawmakers have questioned if competition among energy suppliers has lowered energy bills for average households—the rationale behind deregulation.

The reason so many households were getting turn-off notices around mid-May, Peltier explained, was because the winter bills started coming in around April and the local utility, Baltimore Gas & Electric, began sending out turn-off notices with a 14-day grace period instead of the 45-day extension customers were getting previously under the Covid protections that ended on April 1. The high gas prices this past winter put an additional strain on low-income households, she said.

A Big Toolbox to Fix High Electricity Bills

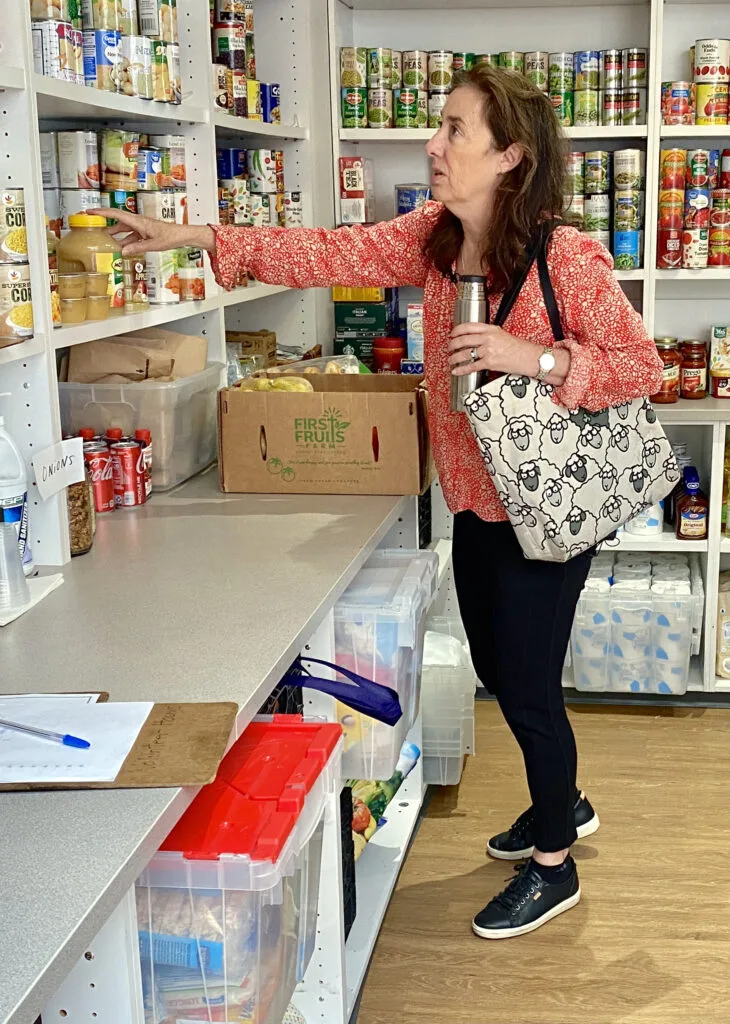

Over the years, Peltier, who first came to Cares in 2016, has become skilled at quickly finding out what brought a person in and how best to troubleshoot their problems. She had a list of questions to help her do that.

“The first question always is: Can I see your actual utility bill, so I can tell if you’re on a third-party supplier?” Peltier said. “Secondly, did you get a turn-off notice? Third, what’s your pre-tax income for the last 30 days?”

By now, she understood that people mostly fell behind because at some point their account got switched to a third-party supplier, which charged them higher rates. “And most of the time, they don’t even know it, like Teresa,” Peltier said.

As Peltier studied McFadden’s bill, Lynaia Jordan, the director of community services at Cares, who sat behind the reception desk, asked walk-ins to print their names on a sign-in sheet before taking their seats in the waiting area. Ringing telephones behind the desk interrupted the chatter.

Amid the clamor, Peltier and Jordan figured out how to help McFadden.

She owed $500 to IDT, the energy retailer, Peltier said, which required her to pay $365 to avoid disconnection. “She did a smart thing and paid $100, and if she pays another $65, Cares can then provide the last $200, which will get her to avoid shut off,” Peltier explained.

Meanwhile, Jordan, using Cares’ relationship with the utility company, had negotiated another seven days to the 14-day termination moratorium. “We will then help her put in an energy assistance application because she’s eligible,” Peltier said, referring to a state-funded program in Maryland that helps low-income people meet their utility costs. Filing the application would put a 55-day hold on a shut-off until her application is processed.

“We’re going to get you fixed up,” Peltier said, as she sat down next to McFadden, and explained what she thought was the best solution. McFadden’s eyes lit up, sensing a breakthrough was at hand. Peltier handed her the energy assistance application to fill out. McFadden picked up a pen and started writing.

The Birth of an Energy Justice Advocate

McFadden’s ordeal reminded Peltier why she became an energy justice warrior in the first place. It began in 2011 with a newsletter she called Green Laurel, which, in 2015, morphed into a weekly column in the Baltimore Fishbowl, a local online publication.

“My strategy was to write a light story, like pollinators and bees. And then I would write about climate change and energy. To me, the two are 100 percent linked,” she said. “Because I was a consumer brand manager before, I was trying to make environmental actions more consumer-focused. Not just for greenies or environmentalists.”

Her next big impetus came from her Episcopal church, the Church of the Redeemer, not too far from Cares’ office.

It was August 2016, she vividly remembered, when her church switched to a third-party energy supplier.

“I thought, third-party supply was great. I read the contracts. I knew the pricing. I love this stuff. And I invited parishioners to an educational talk about it, so they took what we do at church home.”

Competition among retail energy providers often succeeded in driving down prices for savvy commercial and industrial customers, who could understand the fine print and stay current on their accounts.

Next thing she knew, some 50 parishioners showed up for her talk and brought their utility bills, just as she’d asked. She realized many of them had already agreed to switch their accounts to retail companies on the promise of lower rates—but were, in fact, paying more. It was a friend at the church who explained how the bait-and-switch worked.

Now, past midday at Cares, the number of walk-ins and names on the sign-in sheet had swelled. They were African-American, mostly women, and either sat on the seats in the reception area or in an adjacent waiting room.

Taking off her specs, Peltier went to speak with a young Black woman in gray shorts and top who sat on one of the chairs in the lobby.

Sharde Whelchel said she had her power cut off over nonpayment of her utility bill. She looked concerned.

The spiral of misfortune that brought her here involved being a single mother at a young age, being broke, not having a regular income and falling behind on her utility bill, which had ballooned to $1,400. Whelchel was on a third-party supplier account, just as Peltier suspected. She switched her account after a salesman offered her lower rates.

“Whelchel had no idea what was going on and they were charging her a lot more money,” Peltier said, her eyebrows arched. “That to me is really the underlying issue. The last thing you want is a third-party supplier on your bill as a low-income household.”

For a moment, Whelchel’s situation transported Peltier back to that time when her fellow parishioners brought in their utility bills.

Once her friend had explained the sleight of hand, Peltier said she called another friend who happened to work at the Maryland Office of People’s Counsel, a small agency that represents energy consumers in rate cases before the PSC.

“First question I asked, was there any reporting on this? I mean, there must be a lot of people on these third-party suppliers. And then somebody who’s no longer there says to me, ‘Laurel, everybody’s on a variable rate. Everybody’s way overpaying. It’s a mess.’”

She realized her parishioners were all on third-party suppliers—”and were paying double.”

“What on earth is going on?” she wondered.

Asked for comment, Christopher Ercoli, the president and chief executive officer of Retail Energy Advancement League, the trade group advocating for retail choice, said in an email that retailers in competitive markets provide a variety of products and plans. “Electricity supply options have increased greatly for Maryland residents, giving consumers more options for their energy needs,” he said, adding that “retail supplier pricing has generally been about 10 percent lower on an annual basis.”

Ercoli said that state leaders should be increasing education and awareness initiatives so customers can safely and proactively engage in the marketplace.

Now, Whelchel seemed edgy while Peltier looked for a fix for her situation. Peltier told her she needed to terminate the retail contract. Whelchel seemed puzzled, and said the sales representative told her that switching to the company would lower the bill.

“That’s what they dangle to get people to sign up,” Peltier replied. “You have to call them and cancel the contract.”

Third-party suppliers particularly targeted the low-income neighborhoods, according to a recent Berkeley Energy Institute report, which found that energy retailers did so through direct marketing.

The study found that those areas with household incomes below $10,000 a year paid particularly high prices as did the neighborhoods with a large share of non-citizens, residents without high school diplomas and Black, mixed race and Latino and Hispanic residents.

Whelchel’s other challenge was to come up with $1,400 to pay off the bill and have her electricity restored. After Peltier confirmed that she had already applied for her one-time state energy assistance grant of $1,000, Jordan called the Maryland Department of Social Services and found out that it had been approved.

The confirmation allowed the charity to sign off on another $200 in assistance that would get Whelchel close enough to the full amount she owed to get her power turned back on. Then, all she had to do was cancel the retail supplier and get back on a BGE account. Whelchel, clearly relieved, nodded and left, solution in hand.

Damning Data Leads to Legislation

To be able to help people like McFadden and Whelchel, Peltier had worked with journalists and data specialists to uncover the marketing and business practices that third-party suppliers employed to rake in profits, mostly by charging low-income households higher electricity rates.

After the epiphany at her church, Peltier started attending a working group on retail choice that was set up in 2017 by the Maryland Public Service Commission—the state regulator for utility companies—to better understand the phenomenon. She soon realized that these working groups were entirely dominated by representatives of private energy companies and utilities and someone from the Office of People’s Counsel.

“I realized not only is nobody owning this horrendous fleece, this industry has made huge inroads into our state and they have big plans,” she said. “And then something hit me and I just said, ‘Not on my watch.’ Since that day, I have been 100 percent committed to fixing this in our state,” Peltier added.

Her writings for the online weekly Fishbowl soon found traction with the Abell Foundation, a Maryland-based policy think tank, which asked her if she was interested in doing research on the subject.

“They asked, is there any data on low-income households? I said, ‘No, there’s actually no data.’ So, they pushed me if I could go out in the field, and pull some actual data,” she said. That’s what connected her to Cares as a place where she could start figuring out what was going on.

Ultimately, Peltier found the data: a 2018 Abell Foundation report that she co-authored showed that Maryland residents paid an additional $255 million to third-party suppliers between 2014 and 2017, compared to what they would have paid to state utilities such as BGE.

She later updated the analysis with data from 2018 and 2019, which put the total overpaid amount at more than $700 million. Peltier called it a conservative estimate.

In January, Peltier’s group, the Maryland Energy Advocates Coalition, informed Maryland Gov. Wes Moore’s transition team that according to the latest research, Marylanders have overpaid $1 billion on their utility bills since 2014.

“In 2021, 403,000 families paid $290 a year more each for electricity, up from $190 in 2014,” the coalition’s brief said. Nearly 450,000 households in Maryland, or 21 percent of the population, are estimated to be low-income, with 380,000-plus households eligible for the state’s $100 million in energy assistance provided by the Office of Home Energy Programs.

Now, with the clock ticking towards closing time, Alisa Iwumune was next in line. She stood by the counter patiently, occasionally chatting with others sitting in the lobby.

When her turn finally arrived to talk to Peltier, she described the cascade of unforeseen events that had landed her in this predicament. She lived in Indianapolis and had come to Baltimore a couple of days earlier to check on her aunt and her 81-year old friend, Ms. Banks, who had a defibrillator put in last October because of a heart condition and was also recently diagnosed with a touch of dementia.

What worried Iwumune the most was that Ms. Bank’s electricity had been cut off due to an exorbitant $6,000 bill, and the heart monitors and CPAP machine installed by her bedside wouldn’t work without power. “You can imagine what could happen if her heartbeat dropped or if she needed breathing support,” Iwumune said, her gaze fixed on Peltier.

The first thing that went through Peltier’s mind was that Ms. Banks was scammed by a third-party supplier. A “bill that high is very unusual for a little two-bedroom apartment. So, she’s on a [third party] supplier and living in a really inefficient house. But I got a guy, so just cross your fingers,” Peltier told Iwumune.

Most of those who come to charities like Cares are on a variety of federal and state assistance programs, Peltier said, such as Social Security, food stamps, energy-efficiency programs. And the energy assistance programs run by the state of Maryland are often difficult for income-stressed families to access because of clogged, confusing or non-existent phone lines, or an applicant’s limited English, lack of internet access or some combination thereof.

“That’s the reason the Maryland energy assistance program is so under-utilized. This year was the lowest at around 82,000 households, leaving out some 357,000 eligible families,” Peltier said. “How to improve the accessibility of these income-eligible benefits is a problem for many states.”

Keep Environmental Journalism Alive

ICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.

She felt that at least some relief for distressed families was at hand: On July 1, the Energy Supply Reform bill, which the Maryland General Assembly passed In May 2021, became law. The law prohibits retail suppliers from charging customers who are on energy assistance above what BGE charges for gas or electric supply, effectively ending the retail energy ripoffs for those enrolled in energy assistance. Peltier helped write the bill and push it through the legislature.

“That will be a relief for so many struggling families like Whelchel’s, whose energy assistance grant is being pocketed by energy retailers,” Peltier said. About $15 million annually from the state energy assistance grants were flowing to third-party suppliers that were billing households on state assistance year after year, she estimated.

“We have another bill that kicks in on Jan 1, 2024, that will make accessing energy assistance way easier,” she said, referring matter-of-factly to another watershed bill she and the energy coalition managed to shepherd through the legislature in Annapolis.

Signed by Gov. Wes Moore in April, the legislation allows Maryland residents applying for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), or food stamps, to be simultaneously considered for energy assistance, which eliminates the need for a separate visit to apply for energy assistance.

“I’m keeping my fingers crossed,” Peltier said as she walked toward Iwumune, still standing by the desk.

Ms. Banks, Peltier found out by calling a utility contact, was not on a third-party supplier but on the local utility BGE connection. That was puzzling, she thought, because the elderly woman was also in a “critical medical needs” category and the utility was not supposed to cut off her electricity.

Once the electricity is cut off, Peltier told Iwumune, the only way to have it turned back on is by paying off the bill. For Iwumune, that was a big problem. She had to find a way to pay off the $6,000 bill—Ms. Banks was $1,300 short. Iwumune also had to go back to Indianapolis in two weeks.

In the meantime, she had moved Ms. Banks to her house so that her CPAP machine and defibrillator could function while she sorted out the situation.

Peltier, knowing the urgency of the situation, quickly flipped through contacts on her phone, hoping to find people in her network who could offer her advice. She dialed Cindy Carter, a fellow energy advocate, whom she’d known for a long time.

“We’re asking for intervention through a senator and some delegates. And we’re asking for an escalation to the Department of Aging,” Peltier told Iwumune, after getting off the phone. Then she got on the phone again.

The situation got Iwumune to think about her own experience as a caseworker for 18 years, providing information and counseling to patients living with HIV and AIDs, incarcerated men and women, and the homeless, both young and elderly. She found comfort in knowing how she had counseled people in similar or worse situations and believed that something would work out.

“It took me back to church, seeing people suffering like that,” she told Peltier, adding that she retired three years ago hoping for some respite. “And I just go to church and pray to God because I say, ‘Give me strength.’ My mom is doing well. And my girlfriend is a sassy 81-year old. She got cancer three times and beat it,” she said, self-assuredly.

Peltier explained to Iwumune that she’d managed to communicate the urgency to higher-ups of the state Department of Aging and said she was going to speak with a state senator about it later that afternoon.

Then, Peltier and Jordan told Iwumune she had to call other charities operating in the area for financial assistance. Once she did that, they could apply for another $200 from Cares.

Peltier hoped the Department of Aging and her contacts at BGE would restore Ms. Banks’ electricity in the meantime, and once Ms. Banks’ state energy assistance application went in, she would get another 55 days of electric service without the threat of a shutoff.

Iwumune, seeing this elaborate scenario Peltier had managed to construct, teared up. “You are an angel,” she said, almost sobbing, as she folded the papers into her bag.

Peltier replied, “Just dial the other places I told you about and I will also pray that things work out.” She folded her specs.

“In the end, it’s been a total blessing,” Peltier said as she exited the charity’s office, ready to brave the steaming sun outside. “When I said my prayer and asked what I should do with my career, I think this was the answer. I find it very purposeful, and I am 100 percent in the belly of the beast.”

A week later, Peltier got the call from Iwumune, telling her that Ms. Banks’ power came back on.

“Thank God for that,” Iwumune said. And because the application for a state energy grant triggered an automatic moratorium on cut-offs, she added, “we have a 55-day extension.”