Deborah Watts, Emmett Till’s cousin and Emmett Till Legacy Foundation co-founder, and a team of individuals traveled to the Leflore County Courthouse in June 2022 in search of the unserved warrant for Carolyn Bryant—the woman whose claim the 14-year-old boy flirted with her in 1955 led to his murder. Masks and gloves on and hair tied back, the group searched through documents in the basement.

One box in particular that Watts dismissed as inconsequential caught Khali Rasheed’s attention. Ignoring the suggestion to leave it be, he searched the box anyway and found the very thing they had been searching for. “He listened to a higher power. He listened to Mamie. He listened to Emmett,” Watts said of Rasheed at a discussion panel in Jackson, Miss., on Aug. 25, 2023.

After the discovery, Watts called civil-rights attorney and activist Jaribu Hill, who was on her way to the Leflore courthouse to join the search party.

“We found it,” she told Hill.

“What are you talking about?” Hill asked.

“We found the warrant.”

On Aug. 28, 1955, two white men—Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam—kidnapped, tortured and murdered 14-year-old Emmett Till after Roy’s wife, Carolyn Bryant, accused the child of whistling at her. The warrant named Carolyn for the abduction of Till, but a Leflore County grand jury declined to indict her in August 2022; she died in April 2023 at age 88..

Police arrested both Roy Bryant and J. W. Milanmen, and the two went to trial, but an all-white-male jury found them not guilty. They later admitted to killing Emmett Till in a magazine interview. Sixty-seven years later, Carolyn Bryant released a memoir, in which she said she did not want Till murdered.

Jaribu Hill went on to represent the Till family in their pursuit to prosecute Carolyn Bryant, who was still alive at the time, for her role in Till’s murder, but the U.S. Department of Justice and the state attorney general’s office determined that the amount of evidence was not enough to reopen the case and prosecute Bryant.

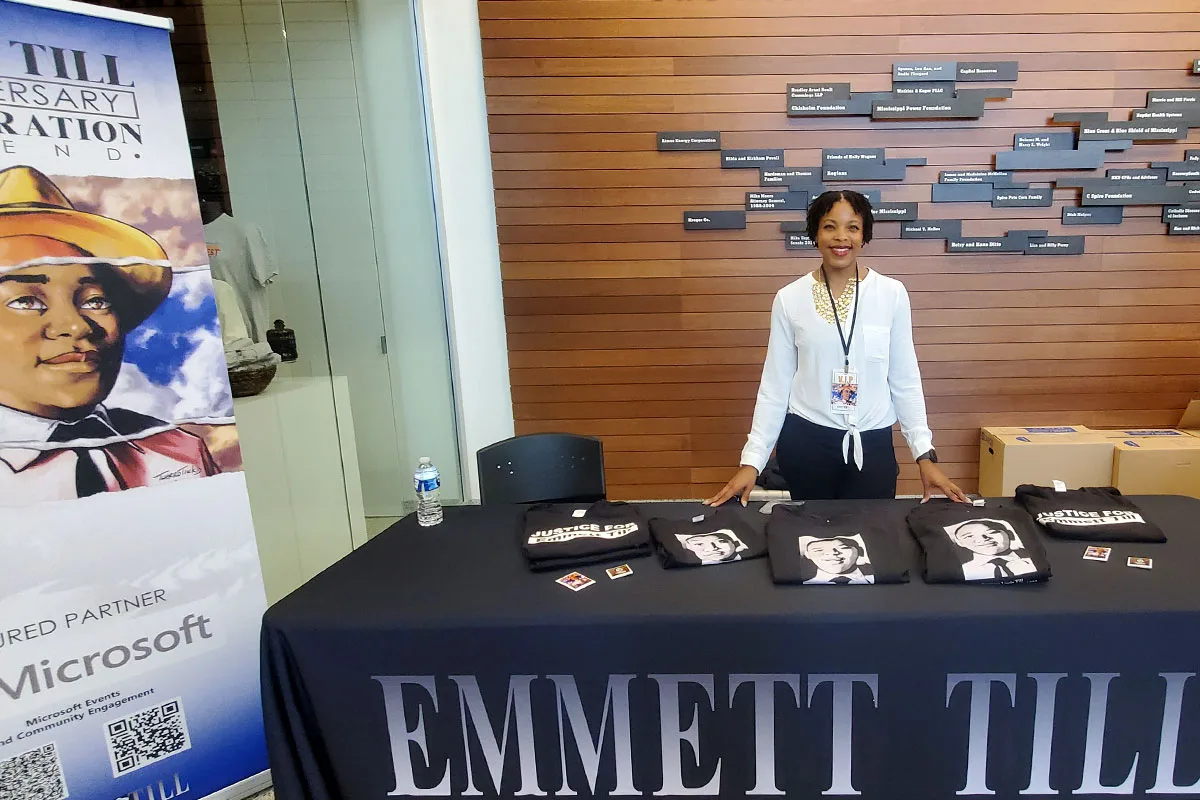

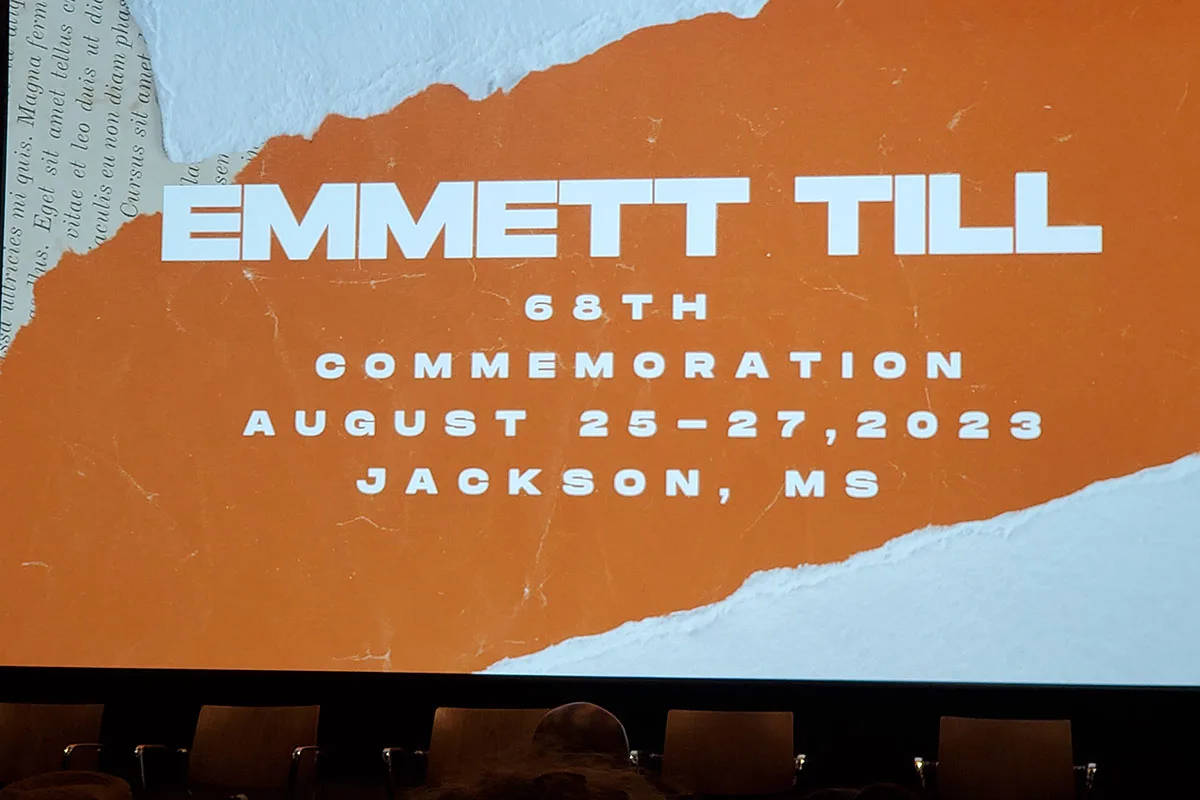

“We were not able to get justice,” Hill said at a screening of the film, “Till,” which the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation organized for the Emmett Till 68th Anniversary Commemoration Weekend at the Two Mississippi Museums on Aug. 25.

“The fact of the matter is the Department of Justice under this president didn’t get it done, either,” Hill continued. “The fact of the matter is (that) the last president, Black man, didn’t get it done. Why? Because white supremacy is supreme.”

The biopic chronicles the murder of Emmett Till and the aftermath of his murder through the lens of his mother, Mamie Till Mobley.

“Until we strike it down blow by blow by blow, we’re gonna see Emmett lynched all over again,” Hill said. “Every day, there’s going to be another Emmett.”

‘Love at First Sight’

“Till” producer Keith Beauchamp learned of Emmett Till at the age of 10 when he found a Jet magazine in his parents’ study. The magazine showed the photograph of Till’s disfigured body, so his parents decided to tell him the story of Till. He grew up near Opelousas, La., and in high school, he began dating interracially.

His parents would always warn him to not let what happened to Emmett Till happen to him, using the tragedy to serve as an educational experience about the racism that is still prevalent in this country.

“It was two weeks before my high-school graduation that I had my real run-in with racism, and that was when I was assaulted by an undercover police officer for dancing with a white classmate,” Beauchamp told the audience.

“And that’s what spurred me into wanting to fight injustice, but I felt the only way that could be possible was if I became a part of the system to fight it,” he continued. “So I decided to study criminal justice at the Southern University of Baton Rouge.”

He wanted to become a civil-rights attorney, but during his junior year in college, a friend introduced him to filmmaking. The same friend asked Beauchamp if he had a story he would want to tell on film, and his answer was Emmett Till. Once he stood firm on his decision to tell Till’s story, he knew he would need to talk to the people who lived it.

Through some research, he found the Emmett Till Foundation’s website, which had Mamie Till Mobley’s name and telephone number listed at the bottom. Beauchamp called it, but when she picked up, he immediately hung up.

“That was only because I didn’t understand the type of life she truly lived,” the producer said. “I didn’t want to open up old wounds. I did not know how to actually express myself to her. But I was mad at myself after hanging up, and I decided to call her back. I called her back, she picked up, and I immediately apologized.”

This event happened in 1995. The following year, two weeks before Christmas, Beauchamp met Mamie Till Mobley in her home for the first time. When he walked in, she was sitting in her kitchen, and their eyes met.

“And if she was here today, because I’ve heard her say this a number of times, it was like when we first met, it was love at first sight,” he said. “She knew everything about me, and we began to talk about the need to continue to tell the story and get justice for her son.”

With her encouragement, Beauchamp would eventually produce a documentary, “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till,” which led the Department of Justice to reopen the case in 2004. Mobley remained a mentor and friend to Beauchamp for eight-and-a-half years before her passing in 2003.

‘They Didn’t Have The Luxury’

Activist Dr. Flonzie Brown Wright had the opportunity to meet and talk with Mamie Till Mobley in the 1960s after Rev. Jesse Jackson organized Operation Breadbasket in Chicago, Ill. Wright was a mother of three who had lost a son as well.

“The movie says she wanted the world to see what had happened to her son, and that is what she said,” Wright said at the screening. “But one on one, she said to me, ‘I want the world to see what hatred has done to my son.’ And we cried together, and we embraced each other.”

“Mamie Till Mobley could not carry hate,” she continued. “You can see the strength of her. If people wonder how Black women get through life, they can look to Mrs. Till as an example.”

Jackson State University Department of Journalism and Media Studies Professor Ashley Norwood said she does not believe traditional media was ever made for Black people. In order for Black citizens to reclaim ownership of their narrative, they have to become the media.

“What we see often is that the mainstream media will profit from our trauma, so it’s up to us,” Norwood said. “For those of us who aren’t in the media, we also have a role when it comes to being mindful about whose voices we are amplifying and what content we share.”

The professor sees Mamie Till Mobley as the best example of someone controlling their narrative. When Mobley received her son’s mutilated body, she decided to have an open casket funeral, wanting the world to see what they did to her baby, she explained.

She invited Black journalists and photographers with Jet Magazine to capture the moment. Mobley also published photos of Emmett smiling and happy, images that juxtaposed his unrecognizable body.

“I don’t think we even understand the gravity of her decision and the impact that still has today,” Norwood said. “I think that humanized Emmett Till, and what that did was prove to be a catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement today.”

“For some of us, it was Trayvon Martin. Tamir Rice. Mike Brown. We saw how the media dehumanized them,” she added. “They didn’t have the luxury of being a young boy, robbed of their innocence and youth. I wish other mothers could control the narrative.”

‘A Revolutionary Movement’

Actor Jalyn Hall, who played Emmett Till in the film, did not know as much as he would have liked to about Till when he landed the role. He credits his mother, who was in the audience, for telling him about Till as a cautionary tale.

“She let me know there would be instances (of discrimination), and she kind of gave me that as a prime example,” Hall said at the panel. “I kind of just went about life knowing the possibility of racial injustice that I might face.”

With so much legislation currently removing parts of history and books involving people of color from educational curricula, the 16-year-old believes creating films highlighting history and historical figures is important. On top of playing Emmett Till, he has also had the chance to play a young Martin Luther King Jr., and he soaked up much information from the film, he said.

“Nothing is minor when it comes to enacting change,” the actor said. “Even the people who just knocked over one domino deserve their own piece. I believe history is the best teacher, and we should definitely put more of that on the screen.”

Adding to Hall’s point, Norwood believes that films like “Till” serve as key educational tools today because she uses them in her classroom. She challenges her students to always create meaningful work that will effect change.

“I think at this point we’ve been entertained enough; it’s time to educate,” Norwood asserted.

As a graduate student at the University of Mississippi, Norwood chose to complete her thesis documentary on the history, perception and culture of majority-Black Greek-letter organizations. She titled her film, “The Fly and the Buttermilk.”

“What I later realized was that it wasn’t just about what was happening at Ole Miss, but instead a microcosm of what a lot of African Americans face in this nation when it comes to prejudice and discrimination,” the professor said. “And a lot of people would consider America the largest predominantly white institution.”

Inspired, Norwood has begun to create a series of documentaries telling Black stories. She encourages creatives to keep creating because our classrooms, our homes and our churches need these stories, she explained.

Despite not getting the justice they so rightfully deserve, Deborah Watts, Till’s cousin, is still proud of the opportunities she and others have taken to at least try. They searched, they marched, and they accumulated 300,000 petition signatures to present to the attorney general. But Mississippi turned its back on them, she said. Again. Still, Watts remains hopeful that other families will be inspired to continue fighting for justice and speak out.

“I think when you answer that call and that obligation, that is a revolutionary movement,” Watts said. “That is a protest. That is a way to move things forward.”