I remember the first time I read the words of the Frenchman Charles Arthaud: “Inoculation, which will surely surprise you, is known and practiced amongst the Negres in some parts of Africa.” By the time I read his pamphlet on smallpox inoculation, published in 1774, I was well beyond surprise. I knew, as many historians knew before me, that free and enslaved West Africans on both sides of the Atlantic were inoculating against disease before the early 18th century. By the time I read Arthaud, I had been tracing this history in colonial-era and medical archival sources in Europe, North America, the Caribbean, and South America for years. It has now been over a decade. Nevertheless, Arthaud’s words, aimed at an audience of slave owners and French colonists, people he presumed would be unaware of this story, drive home a different point: that the African and African diasporic history of inoculation is as much about the politics of commemoration as it is about the history of medicine.

Most historians cite 1721 as turning point in the history of smallpox inoculation in the Americas. 1721 was a terrible year for smallpox. Horrible epidemics struck the Caribbean, North America, Western Europe, and the West African coast. As the disease raged around the Atlantic, an enslaved African man in Boston recalled how people addressed smallpox in his West African homelands. He explained that, for generations, after doing what they could to prevent the disease from spreading, his people used a medical practice to control how smallpox spread. The method he described was one that Europeans called “smallpox inoculation,” or “variolation.” It involved deliberately infecting someone with the disease by pricking someone else’s smallpox pustule, removing some pus, and placing that pus inside an incision on the recipient’s arm or thigh. The recipient would come down with the disease and recover, ideally in a controlled environment. Amid the chaos of epidemics, this practice enabled communities to have some semblance of control over how, when, and to whom smallpox spread. This enslaved African man explained that the practice was a last resort for most but that some “brave young men” would seek out smallpox outbreaks to be inoculated so that they could “go and trade anywhere without fear.”

Imagine: a young Black man being able to go anywhere—anywhere at all—without fear. Unfortunately, this is so difficult to imagine in our world today. Any such days of fearless travel and trade would have been behind this enslaved African man too. Enslavement in 18th-century Boston would have limited his mobility. To Benjamin Colman, the Puritan minister who recorded his account, this enslaved man was nothing more than an anonymous “poor Negro.”

This man was not the only Black man in Boston to inform Puritans about smallpox inoculation. More well known among medical and early American historians is the case of Onesimus, a man enslaved by influential Puritan minister Cotton Mather. Though many historians and journalists, writing for academics and the general public, have heroized Onesimus as a sort of father of inoculation in the Americas, their narrow focus on the singular figure occludes a much bigger historical narrative. Mather and many other Puritans first learned of inoculation from Onesimus. However, in his other writings, Mather cites an “Army of Africans” who knew about inoculation in Boston. The demographics of the African community in Boston, and the specific characteristics of the geographies and societies men like the man who spoke with Colman described, suggest that the majority of this “Army of Africans” hailed from sub-Saharan West Africa.

While conducting archival research, I quickly learned that these men were not alone. When I began my research, I expected to see only a handful of records. But we find, peppered throughout the annals of medical treatises and travel narratives describing the Americas and West Africa, descriptions of enslaved and free sub-Saharan West Africans practicing smallpox inoculation, something they claimed to have done since before the introduction of Islam and since “time immemorial” in West Africa. I have since found accounts of the practice concentrated in the sub-Saharan African regions that today include Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin, and parts of Nigeria, as well as in the Caribbean and North America, specifically present-day Haiti, Jamaica, Massachusetts, and New York. These sources reveal that smallpox inoculation was a widespread West African healing practice.

Smallpox inoculation coexisted with other forms of inoculation in these societies. For example, we find examples of enslaved Africans who hailed from present-day Ghana describing inoculations for yaws, another contagious flesh disorder. The surviving descriptions are often vague and tell us little about the inoculators or inoculation recipients beyond whether the procedure was successful and the ideal time to perform it, when children were young. Nevertheless, this abundance of archival evidence has gone largely unstudied by historians, who have instead chosen to fixate on Europeans’ perceptions of Onesimus or give West African inoculators only passing mentions in their histories of the practice. This is unsurprising, as canonical histories of medicine rarely grapple with the histories of Africa and the African diaspora.

West Africans were not the only ones to practice smallpox inoculations before the 1700s. There are numerous accounts of North African, Arabian, and East Asian inoculators as well. Some of them practiced inoculation by making incisions (similar to West Africans), while others snuffed dried smallpox scabs to be inoculated. What was similar about these practices was that, rather than focusing on healing individual bodies, they centered and addressed whole communities. As the anonymous enslaved African man who spoke to Colman described, inoculation was about far, far more than preventing smallpox mortalities. This was a collectivist practice that enabled West African, North African, Arab, and East Asian groups to preserve themselves against the scourge of disease, and travel and trade without fear. It enabled them to have intergenerational connections and opportunities beyond their homelands. It likely enabled many to thrive.

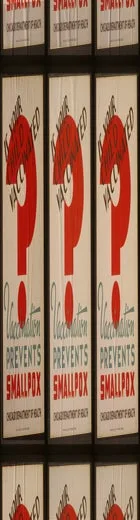

My research reveals that enslaved Africans were responsible for introducing the practice of smallpox inoculation throughout the Americas by the 1700s. A century later, in the 1790s, in England, Edward Jenner invented the cowpox vaccine, the world’s first vaccine, an advancement that would transform how smallpox was treated worldwide. However, Jenner drew on nearly a century of inoculation knowledge and practices that were a crucial part of African, Arab, and East Asian healing. Nevertheless, today most people still associate inoculation and vaccination with Western European medicine and public health, despite their non-Western roots. This is, unfortunately, partly the fault of historians who have lauded Jenner but overlooked the legions of Arabs, Asians, North Africans, and—most of all—West Africans who practiced inoculation. West African histories of inoculation remain understudied in part because the archival evidence is so dispersed, and in part because historians of medicine have tended to ignore West Africans’ histories of medical knowledge production and innovation.

It is essential that we recognize the non-Western roots of medicine and public health because they have a bearing on our present. Recalling and commemorating the non-Western history of inoculation, particularly its African history in West Africa and the Americas, is necessary to help heal the gaping wounds that have engendered medical mistrust in Black communities globally. Overemphasizing European and Euro-American histories of inoculation not only is dishonest but also suggests that inoculation methods do not have a place in African and African diasporic healing traditions, when in fact they do. While we often center 20th-century Black American histories in public discourse, it is imperative that we also remember the earlier transatlantic histories, including medical histories that transpired in the era of slavery, especially when they laid the foundation for modern medicine.

While remembering, we must also ask: What is owed? How do we pay homage to the generations of free and enslaved Africans who helped lay the foundation for modern public health? How might we move beyond a commemoration practice rooted in recognition and representation to one that has tangible results for Black people? How might this historical knowledge add to calls for reparations?

Black thriving is possible. It must be. Respecting and commemorating the history of African and African diasporic inoculation practices entails creating and allowing for the conditions for Black people’s thriving globally—conditions that would create a world in which Black people might live without fear. Those conditions include a world where health care is free and easy to access, a world bent on addressing the climate crisis, a world without prisons, detention centers, policing, and rising fascism, and a world in which we are not conscripted to be cogs in the machine of racial capitalism and militaristic neo-imperialism or broken under the thumb of both. That world is possible. And it is owed.