He was the first Black person to sail alone by way of the arduous southern route, rounding the perilous Cape Horn and withstanding storms and loneliness.

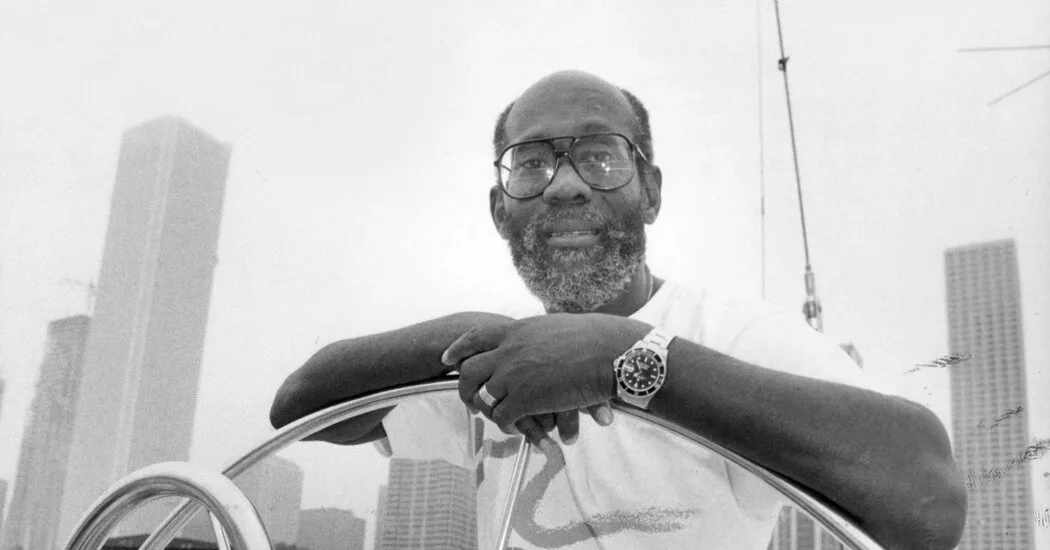

Bill Pinkney, the first Black sailor to circumnavigate the globe alone by the arduous southern route — rounding the five great capes of the earth’s southernmost points of land, most notably the fearsome Cape Horn — died on Thursday in Atlanta. He was 87.

His death, in a hospital on a visit to Atlanta, was announced by Ina Pinkney, his former wife, who said he sustained a head injury in a fall earlier this week. He lived in Puerto Rico.

Cape Horn, the southern tip of South America, is where the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans meet in a treacherous scrum of churning waves battered by capricious winds called williwaws. It is known as the Mount Everest of sailing, “a mystical, mythical way point,” as Herb McCormick, the former editor of Cruising World magazine, put it in a phone interview. Those who round the cape become members of an elite club.

Mr. Pinkney, aboard his 47-foot cutter, Commitment, joined that club on Valentine’s Day in 1992 in a driving rain and with bare masts: He had dropped his sails because the wind was so ferocious, yet the waves and current were so powerful, he still bucketed along, on course, at five knots. He’d been at the helm for 48 straight hours, but he made sure to clamor down below to don a gold earring — a tradition followed by those who make the passage — pop the cork of a bottle of champagne, toss a few streamers and videotape his solitary celebration to send to the 30,000 children back in the United States who had been following his journey.

Nearly two years before, in August 1990, Mr. Pinkney was a month shy of his 55th birthday when he set sail out of Boston Harbor. He would cover 32,000 miles before his return in June 1992, having endured all the frustrations and outright perils of the solo blue-water sailor — lack of sleep, broken gear, ripped sails, terrifying storms and piercing loneliness — as well as its quiet and often profound joys. (He took up needlepoint to pass the time.)

Sailing into Cape Town after a month at sea, and leery of what he might find in a country still ruled by racist “color” laws despite Nelson Mandela’s release from prison the year before, he raised a spinnaker he had designed in the colors of African American pride: red, black and green.

“I wanted all to see who I was,” he wrote in his 2006 memoir, “As Long as It Takes: Meeting the Challenge,” “and where I came from.”

Mr. Pinkney had grown up on the South Side of Chicago, raised by his mother, who worked as a maid. They moved often, and for a time were on public assistance for dependent children. Mr. Pinkney hated being sent to the welfare office to pick up the monthly ration of potatoes, powdered milk and so-called government cheese. He thought he might be an artist, but his mother, by his account, warned him off: “The only people who make money in art are dead white men,” she told him.

He graduated from a technical high school, having pivoted his ambitions to architecture, but ended up joining the Naval Reserve hoping to travel and see the world. He encountered racism from the get-go: He wanted to specialize as a hospital corpsman, but was encouraged to be a “steward’s mate,” essentially a valet to the officers, where he “could be with his own kind,” he recalled one personnel officer telling him. Mr. Pinkney prevailed, went on to train as an X-ray technician and served on various ships.

After he left the service, Mr. Pinkney, a gregarious, curious and restless man, worked as an elevator mechanic, a limbo dancer (at which he excelled), a conga player, a makeup artist on soft-porn films and then on more conventional fare, a cosmetics executive at Revlon and other companies, and a public information officer for the city of Chicago. He had fallen in love with sailing while living in Puerto Rico after his Navy service, a bittersweet period, he wrote in his book, because he had moved there after fleeing an early marriage, leaving his young daughter behind.

“I became what too many Black men became,” he wrote in his book, “‘a deserter.’ I ran then and in some ways am still running.”

He lived for a time in New York City and crewed on friends’ boats in the Northeast; he was always the only Black man on board. (He also sailed model yachts in a Central Park pond.) And while in New York he converted to Judaism, the culmination of a spiritual quest that he had embarked on after his divorce and that sustained him on his journey years later.

Mr. Pinkney began sailing in earnest on Lake Michigan when a job took him back to Chicago. His first sailboat was a 28-foot Pearson Triton he named Assagai, for an African spear. When he turned 50, having climbed the corporate ladder, he asked Ina Pinkney, whom he had married in 1965, if she would be unhappy if he went to sea. “I’d be unhappy if you didn’t go,” she told him.

He conceived of a solo circumnavigation as a way to inspire his two grandchildren — he had reconnected with his daughter when she was an adult — and began to develop an educational program, Project Commitment, for school children in Chicago and Boston to follow his journey. But it would take years to raise the funds for the mission, though he had seed money from Armand Hammer, the oil magnate and philanthropist. Mr. Pinkney’s appeals for support were rejected by a Who’s Who of industry, from Eastman Kodak to Procter & Gamble, as well as a slew of Black-owned businesses, whose rejections stung the most. Oprah Winfrey, too, politely declined.

When The New York Times reported on his plight in 1989, however, the head of an investment firm in Boston named Tom Eastman and his colleagues signed on to fully bankroll the journey. (As part of the arrangement, the boat, Commitment, would be sold at the end of the voyage.)

Mr. Pinkney originally planned to circumnavigate the globe along its middle, using the Panama and Suez canals. Ted Seymour, of Newport Beach, Calif., had been the first Black man to sail that route, in 1987. Yet at the encouragement of Dr. Hammer, he flew to England to meet Robin Knox-Johnston, the first man to complete a nonstop solo circumnavigation, in 1969.

Mr. Knox-Johnston urged him to reconsider his “kiddie cruise,” as he called the passage through the canals, and travel the southern capes, the old fashioned way, as he had done in a sturdy 32-foot-long boat and as the great clipper ships had done. And, he emphasized, Mr. Pinkney would be the first Black man to do so.

William Deltoris Pinkney III was born on Sept. 15, 1935, in Chicago. He was named after both his father, who worked as a handyman, and paternal grandfather. His mother, Marion (Henderson) Pinkney, divorced his father when Bill was 6 and raised Bill and his sister, Naomi, by herself.

Bill was a reluctant student — the racism of his teachers and fellow students were not a goad to learning — but an avid reader, and in seventh grade he became enthralled by “Call It Courage,” a 1941 Newbery Medal-winning story by Armstrong Sperry about the legend of a bullied Polynesian boy who is terrified of the ocean before setting off in a canoe to conquer his fear. It sparked something in young Bill.

After his historic trip, Mr. Pinkney went on to become a trustee of the Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut, where he oversaw the building of a replica of the Amistad, the Cuban schooner that West African slaves commandeered in 1839 as they were being transported to the Caribbean. In a landmark case that reached the Supreme Court, dramatized in Steven Spielberg’s 1997 movie “Amistad,” they were allowed to return to their home country.

Mr. Pinkney was the replica’s captain for a few years, overseeing its use for sail training and education. He also led a group of teachers and school children on an 85-foot ketch to retrace the Middle Passage route that slave ships took from Africa to the Americas, and created a program for middle school children on the African slave trade.

In recent years Mr. Pinkney ran a charter boat business in Fajardo, P.R., on the island’s eastern tip, with his wife of nearly two decades, Migdalia Vachier Pinkney, whom he met salsa dancing. She survives him, along with his sister, Naomi Pinkney; his daughter, Angela Walton; and two grandchildren.

He and Ina Pinkney divorced in 2001, but they remained close. “My life was the sea, and hers was on land,” he told The Times in 2019 in an article headlined “The Perfect Divorce.”

In 2021, Mr. Pinkney was inducted into the National Sailing Hall of Fame, which honored him with a lifetime achievement award.

Sailing is about escape, Mr. Pinkney wrote in his book, “escape from the bonds of conformity, racism and lack of respect because of one’s background. It can be the means of achieving a goal, but sometimes it can be a source of discovering alternatives to your conventional path.”

He added: “This is because the sea does not care who you are, what your race or gender is, how much wealth or power you have, or even what flag or political system you embrace. The sea treats everyone the same.”