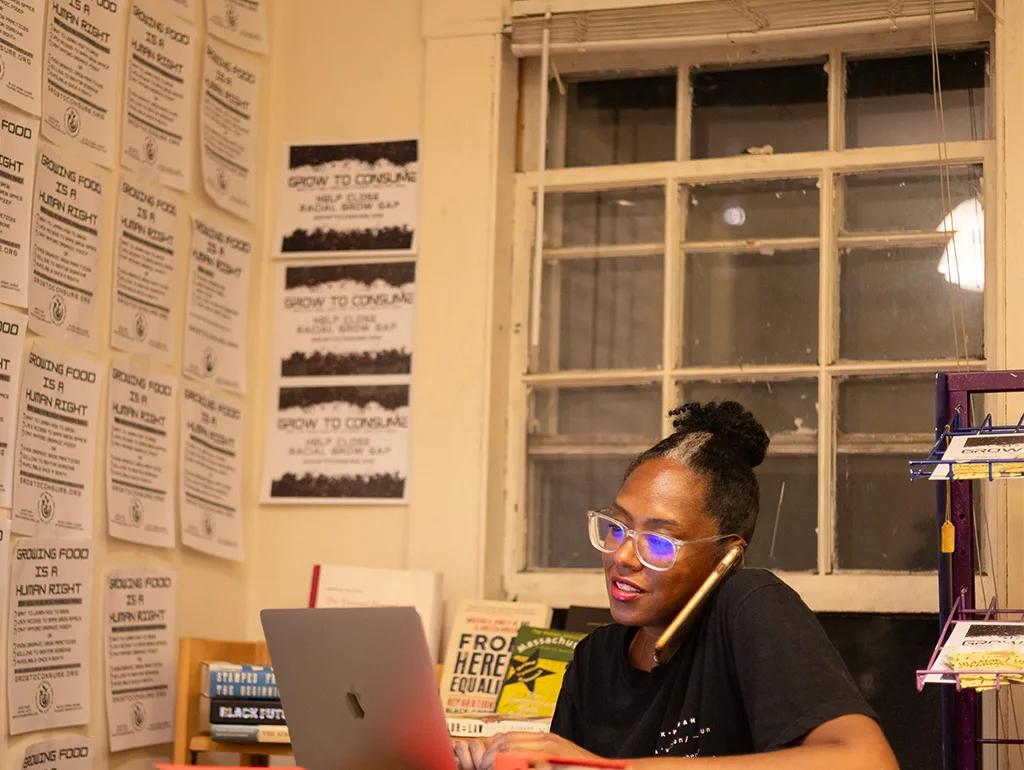

Saskia VannJames works Thursday in her offices at the Democracy Center in Cambridge’s Harvard Square. (Photo: Kate Wheatley)

A group of city councillors are preparing an order seeking the creation of a commission to oversee a Cambridge reparations process helping correct wrongs dating back to the founding of the county and its Jim Crow era, which dismantled wins from the Civil War. The motion leans heavily on work by Saskia VannJames, who presented to the council’s Civic Unity Committee on Aug. 21.

Goals proposed by VannJames would include recognition of a class of residents who are American Freedman – the descendants of enslaved people – and participation in similar efforts on a statewide and eventually federal level. But the work starts with a commission.

“We have a commission for immigrants already, a commission for human rights, a commission for the LGBTQ and for women, we have a commission for everybody except for American Freedmen. And so we’re carving out this space,” VannJames said Tuesday.

The call for a truth and reconciliation task force proposal was asked of the committee before the end of September; implementation of the task force was asked before elections Nov. 7.

Councillors at the hearing praised VannJames’ work and took the suggestions seriously, with chair E. Denise Simmons saying a group would draft the order quickly and councillor Quinton Zondervan proposing a key change to ensure it happened as they hoped: They wouldn’t pass a policy order asking for a task force, which is handled by city staff, but enact a law calling for a commission.

“It’s entirely possible that even if the council unanimously passed this policy order in September, that no appointments are made,” Zondervan said. Voting a law would make a commission a requirement with a timeline.

Simmons agreed that the issue was too important to become mired. “The idea of an ordinance makes good sense,” she said, promising that the work would be done within the next few days.

A thousand conversations

When two reparations and restitution proposals came up in City Council meetings in 2021, VannJames stood during public comment to call them misguided. The orders were tabled in favor of getting more input from the community – a task that fell to VannJames, a policy director with the state’s cannabis-focused Recreational Consumer Council and the co-founder of Grow to Consume, an organization that helps black people find urban agricultural space and learn to cultivate organic food.

VannJames’ volunteerism became two years of law study, meetings and attending reparations conferences – eventually becoming a panelist – with days stretching from 6 a.m. to crashes “somewhere between 10 to midnight,” only to start over again the next day, much to the frustration of family, VannJames said. She also got that local input. “It’s about going into the community and having a cup of tea and listening,” she said. “Letting the people who have been harmed name those harms, and taking notes and putting it together.”

All told, VannJames estimated that she spoke with 1,000 people in preparation for the Aug. 21 hearing.

Poring over documents was another nearly literal mountain to climb. The research cites a legal framework from the United Nations and the example of a “harm report” out of California – a crucial step because a reparations process demands precision on identifying the injury that’s being addressed. “I can send you guys the link,” VannJames told councillors. “When you click on it, just go take a shower and come back in 20 minutes. Hopefully, it’s loaded by then.” When she printed it, front and back, it wound up being around 6 inches thick.

Presentation to the committee

Out of the work came an 18-slide presentation that parses the differences between transitional and reparative justice; an overview of reparations and proposed solutions; and a survey of immediate and long-term goals.

One call is for Cambridge to support a bill now on Beacon Hill (“An act to cure us of the liabilities that ultimately restricted equity”), introduced by state Rep. Fluker Oakley of Boston and written with Antonia Edwards, leader of the national grassroots reparations group, SoliDarity.

Edwards called into the hearing to endorse VannJames. “Everything that she said is absolutely right,” Edwards said, and reparations “has to start with American Freedmen – the 4 million formerly emancipated slaves.” It’s a term bestowed by the U.S. government in the American Freedmen Act of 1865, which created an American Freedmen Bureau, bank and a system of hospitals. Notoriously, government officials promised 40 acres and a mule, but it was enslavers who wound up getting reimbursed after the war for losses; not only did the allotments of land never get made, but Jim Crow government broke up the benefits from the act of 1865.

That intersects with VannJames’ currently more modest mission at Grow to Consume: “Massachusetts never gave out 40 acres to American Freedmen. I still want my 40 acres,” she said.

“We have to think big”

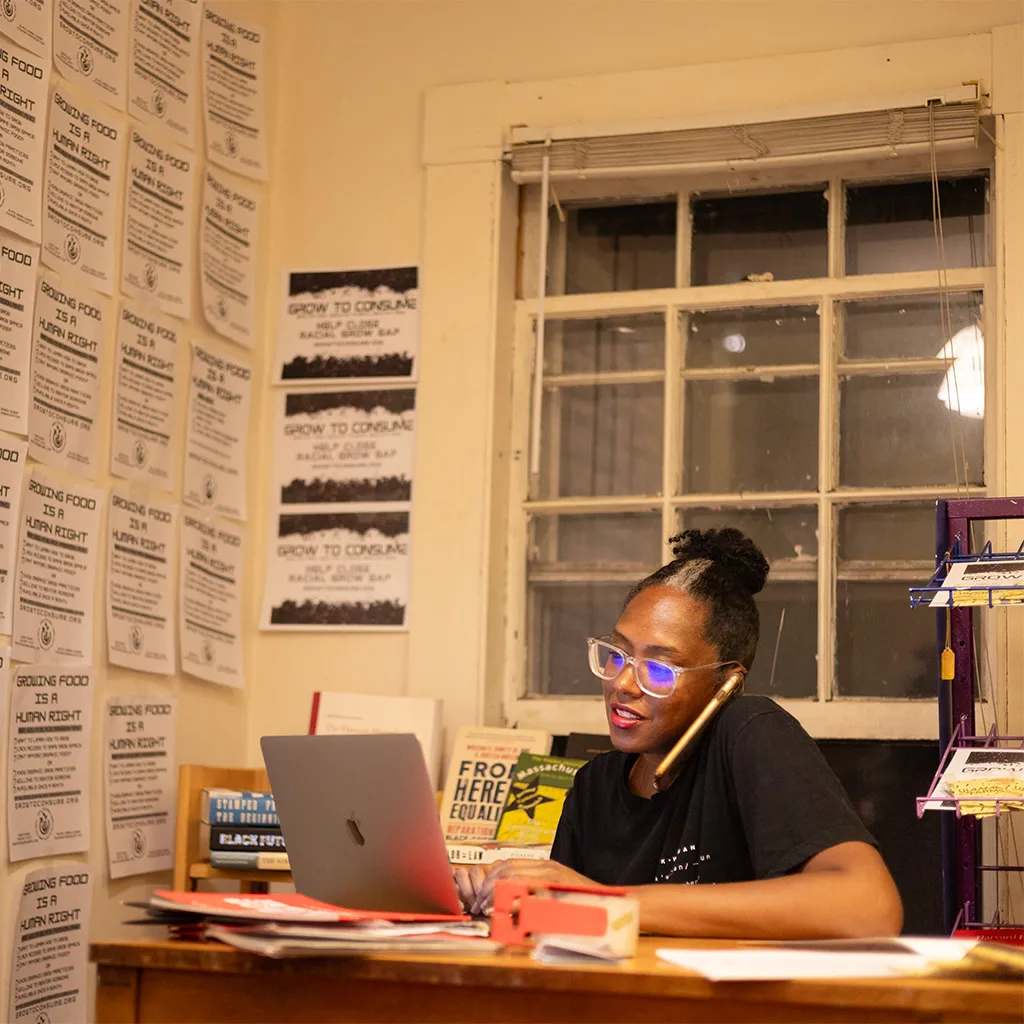

VannJames on Thursday with a folding chair alluding to the Montgomery, Alabama, riverfront brawl of Aug. 5, resulting from a potential hate crime. (Photo: Kate Wheatley)

She was briefly in tears Tuesday talking about the hollowing out of neighborhoods of people like herself, to the point that in Cambridge “you can’t find five American Freedmen to play basketball with five other American Freedmen. We’re today’s Native Americans, meaning: Where are we? Where did we go?” VannJames said. “We’ve been successfully displaced.”

Councillor Dennis Carlone suggested that early childhood education was one obvious form of correction to provide for generations of achievement gaps.

VannJames saw more. “We have to think about heritage-based schools – we have to think about Freedmen schools,” she said. “We have to think about renaming Harvard Square into Freedmen Square. We have to think big, and we have to think radical to successfully overcome the normalized, race-based ideology that exists in our town.”

“We need the Freedmen’s Bureau to come back. And we need the Office of Freedmen Affairs to properly sort through that,” she said.

Reparations is not about a check

Some of VannJames’ findings and conclusions may surprise. She is blunt, for instance, that people are wrong to think that reparations is about writing a check, and she does not expect Cambridge to do such a thing. “The true cost is beyond the city budget – let’s just acknowledge that. This number is going to be huge. There is no number. They’re not going to be able to pay it. We know it,” she said.

What is realistic is to be provided repair services, be recognized as American Freedmen instead of by race and to get support for larger efforts that will emerge from the new state and federal offices and bureaus, she said.

She also acknowledged the headwinds faced by reparations proposals. “Our Supreme Court is saying it’s against the 14th Amendment to have race-based ideology. Anything based upon race isn’t going to fly,” VannJames said. That’s why reparations arguments are focused on human-rights violations and not race, and why VannJames demands that the identity of “black” be eliminated in the conversation.

“It’s our government insisting that we identify as negroes, as colored, as black, as African American, as Afro American, as mulatto,” she said. “And the truth of the matter is there’s only one race,” which includes the identity of American Freedmen – which includes people with a mix of indigenous blood, African blood and “we have to reconcile with the truth that we have European blood in us as well.”

Reparations are needed because “everybody has a heritage, a homeland to claim, they have sovereignty – except for American Freedmen in America,” VannJames said.

Two events

Tony Clark prepares to speak June 7, 2020, at a rally on Cambridge Common. (Photo: Marc Levy)

Two reparations-themed events are planned in Cambridge this month: VannJames’ “funky good time” at the Freedmen Land Block Party at 1 p.m. Sunday on Fern Street, south of Danehy Park in Neighborhood 9; and a more serious-minded film screening and discussion on “Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery” that is co-hosted by My Brother’s Keeper Cambridge with Harvard’s $100 million initiative to grapple with its past. It’s at 5:30 p.m. Sept. 19 at the Cambridge Main Library, 449 Broadway, Mid-Cambridge.

Tony Clark, co-founder and co-president of the MBK chapter, agreed Tuesday that a focus on reparations as a dollar amount was short-sighted, including Harvard’s $100 million. “How can we have other conversations in terms of career ladders for people of color in the municipal government? When we look at housing stock, what does that look like? From an equity standpoint?” Clark said, noting that overall arrests in liberal Cambridge are down, while arrests of black and brown people are up.

He wants more systemic improvements than are offered by such things as the city’s temporary guaranteed income program, and is watching what VannJames does with interest, as well as efforts in Amherst and Providence, Rhode Island – where he saw a Brown University program become increasingly “sanitized.”

“I’ve been impressed by the diligence” of VannJames, Clark said. “But I’m always a little skeptical about where will the votes lie? How authentic will the Cambridge policy look after a number of reads?”