STEPHEN GLOVER: Nothing can undo the sins of slavery, which is why this misguided modern obsession with reparations leads us into a moral quagmire

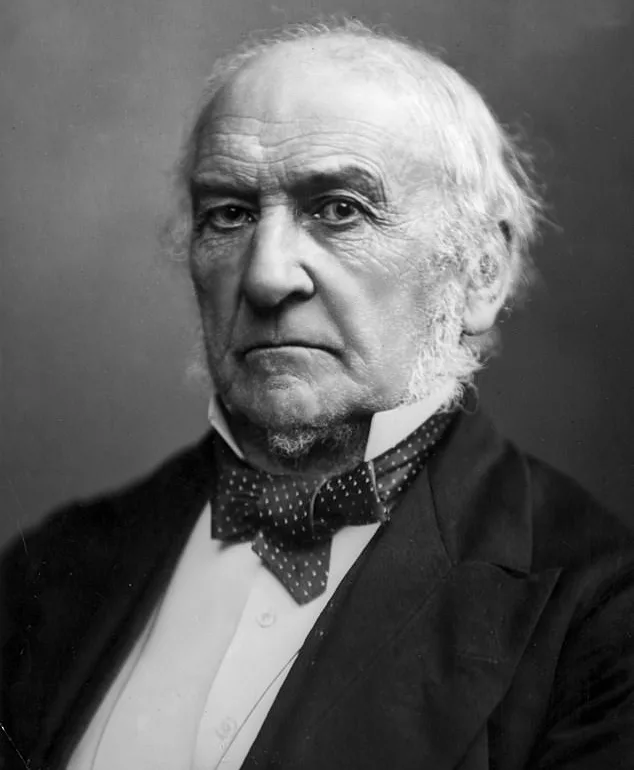

William Gladstone was probably our greatest reforming prime minister. He was a brilliant man, if sometimes long-winded. On one occasion, as Chancellor, he delivered a Budget speech lasting nearly five hours.

During his first stint as prime minister, the 1870 Elementary Education Act was passed, making schooling compulsory for all children between the ages of five and 13. This was one of the most far-reaching measures in British history.

But great man though he was, Gladstone had the misfortune to have a father, John, who was one of the most prominent slave owners in the British Empire. A rebellion by slaves on one of his sugar plantations in British Guyana in 1823 led to more than 250 people being killed and 51 sentenced to death.

That John Gladstone was a bad man is incontestable. It’s easy enough to make that judgment now, of course, but his brutal suppression of the rebellion shocked even his contemporaries.

William Gladstone was at first loyal to his father. In 1831 – two years before the abolition of slavery in the British Empire – he made a speech as a young Tory MP arguing for compensation for slave owners. And, indeed, John Gladstone was handsomely rewarded for his sins, receiving the equivalent of about £10 million in today’s money.

As William drifted towards the Whigs (or Liberals), though, he took a far more critical view of slavery. In 1850, he described it as ‘by far the foulest crime that taints the history of mankind’.

Such is the background to a decision by six of John and William Gladstone’s descendants to pay ‘reparations’ of £100,000, which will be used to fund research into the impact of slavery. They will then make a public apology at the University of Guyana’s International Institute for Diaspora and Migration Studies.

This follows a similar gesture by the Trevelyan family, including former BBC reporter Laura, whose ancestors owned a plantation on the Caribbean island of Grenada. They have also apologised for their forebears’ wickedness, and paid out £100,000 by way of reparations.

The actions of the present generation of Gladstones and Trevelyans are perfectly understandable. Few of us would relish having a slave owner as a direct ancestor. And John Gladstone was especially unpleasant.

Even if £100,000 seems a token payment – the Trevelyans and, perhaps particularly, the Gladstones are very rich indeed – it’s better than nothing. And there is surely little harm in making an apology on behalf of long-dead people who can’t speak for themselves.

Yet other than salving the consciences of the families concerned, one must ask whether any useful purpose is served by these gestures. (And why were both families so anxious to publicise them?) The obsession with reparations is wrong-headed, and could become dangerous.

For one thing, I dispute whether it’s possible to apologise on behalf of dead people. We can’t speak for them. The most we can say is that we are desperately sorry that slavery happened. I’m certain most of us are.

It’s also the case that the victims of European slavery are long dead too. Neither a token payment nor a large amount of money can ever help those people in the slightest degree, or reverse the injustices meted out to them.

So what exactly is happening here? If an expression of sorrow at the cruelties of the past were considered sufficient, I would be delighted to make it. But something more is demanded of us.

Abasement is called for, followed by the transfer of a sum of money. How and when the process will end isn’t clear. All that we can be sure of is that it’s going to be long, divisive and bitter.

Those like the historian David Olusoga who argue for reparations – he recently asked the Royal Family to follow the Church of England in making a large restitution – appear unaware of the moral quagmire into which they are leading us.

For if the descendants of slaves must be compensated, so should the descendants of countless others who have been abused, tortured or murdered in the past. What about the six million Jews exterminated by the Nazis?

Why, if reparations are sought for the descendants of slaves, should those whose families were murdered in the Holocaust not be compensated? If anything, their claim is stronger, since many of them are still alive.

Must the German government pay out billions of euros to the relatives of those killed by the Nazi war machine? Or the Japanese government compensate the children and grandchildren of thousands of British prisoners of war mistreated or left to die in barbaric Japanese camps?

That is the logic of the campaign for restitution for the descendants of slaves. And yet, strange to tell, we hear very little about the need to look after those whose forebears died within living memory in concentration camps, gulags or other abysmal places where modern men have behaved like beasts.

Equally, activists restrict their demands to European countries. Yet many other peoples in the Arab world and even in Africa itself (think of Benin, in modern-day Nigeria, or the Ashanti in Ghana) were embroiled in slavery, either on their own behalf or in the service of Europeans. Should they also be paraded in the court of history, with apologies extracted from them and large reparations paid?

Well, you can be absolutely sure they won’t be. The call for restitution is one-sided, and the only transgressors are the representatives of European culture.

There is an ideological battle being fought in which selective history is used for political ends. Some clever people on the Left have come up with a novel idea for appropriating some of the assets of the developed world, though in fact very few of them derive from slavery.

Onto this battlefield the good natured if somewhat naïve Trevelyans and Gladstones have strayed, seeking to soothe their consciences in return for digging into their pockets for some small change, and offering apologies that are not, in reality, theirs to make.

Where will it end? With us subsiding under a tsunami of guilt? Your great, great grandfather may have worked in a cotton factory whose cotton was picked by slaves. Or you may have had a great, great aunt who had shares in a business in the American South.

But we are not all guilty. A few of our ancestors were, but they’re dead; and the people they abused are also dead. We are not the guilty ones.

Yesterday, I awoke to hear about a report, appalling if true, by the usually reliable Human Rights Watch. It alleges that hundreds of people, many of them Ethiopian migrants who have crossed war-torn Yemen, have been shot dead by Saudi border guards.

That’s the same Saudi Arabia which is a close British ally, whose prime minister, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, has just been invited on an official visit to Britain later this year, when he will be greeted by the King.

Let’s concern ourselves with bad things happening now. Nothing in the world can be done to undo the sins of slavery. We can only resolve never to allow such terrible acts again.