Some form of slavery has been in existence throughout much of human history. But the Atlantic Slave Trade between 1440 and 1863 was easily the most vicious case.

More than nine million Africans were enslaved and transported across the Atlantic Ocean by European traders, with Britain to the fore. British captains like Francis Drake and John Hawkins shipped slaves from the 1560s onwards. King Charles I set up the Guinea Company to trade slaves in 1631, and his son, Charles II, founded the Royal African Company to re-launch the slave trade in 1672. In the 18th century, ships out of Liverpool, Bristol and London made Britain the biggest slave trader in the world. Fully 3.2million enslaved Africans were taken across the Atlantic in British ships.

The journey across the Atlantic Ocean, called the Middle Passage, was hellish. The slaves were chained in overcrowded holds without sanitation or clean water. Between 1789 and 1805, 14 out of every 100 slaves died from dysentery, tuberculosis and infected wounds.

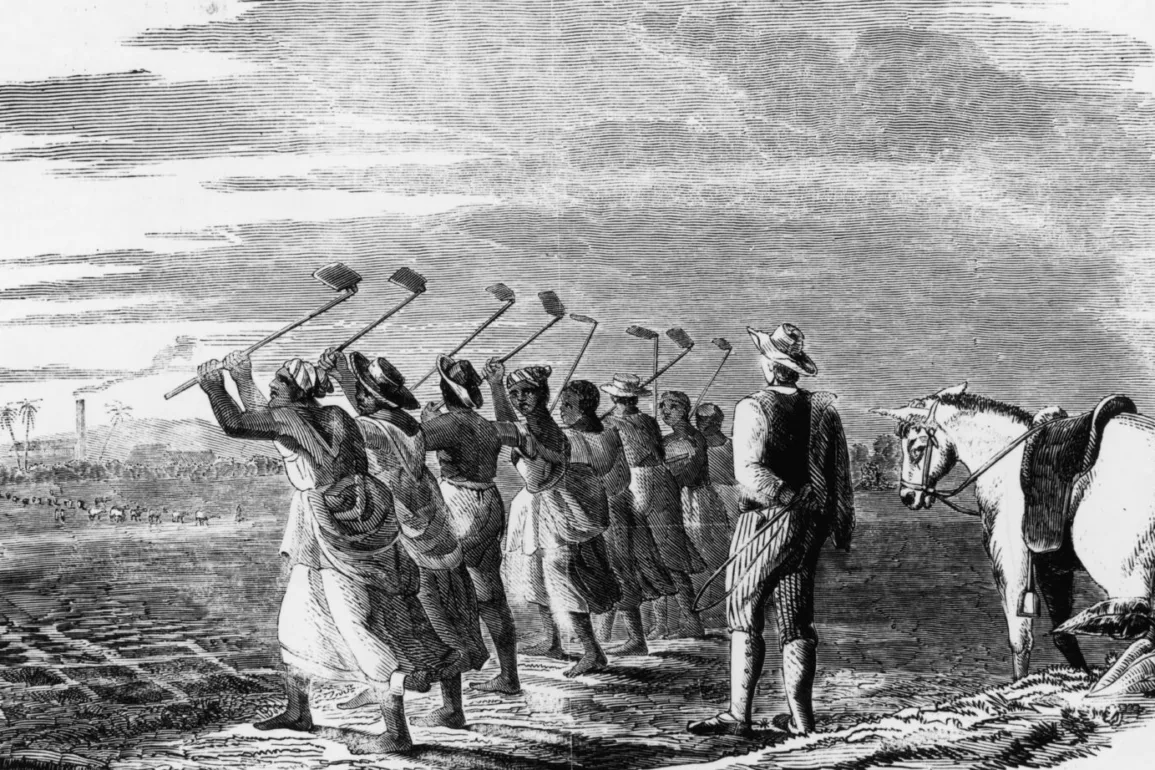

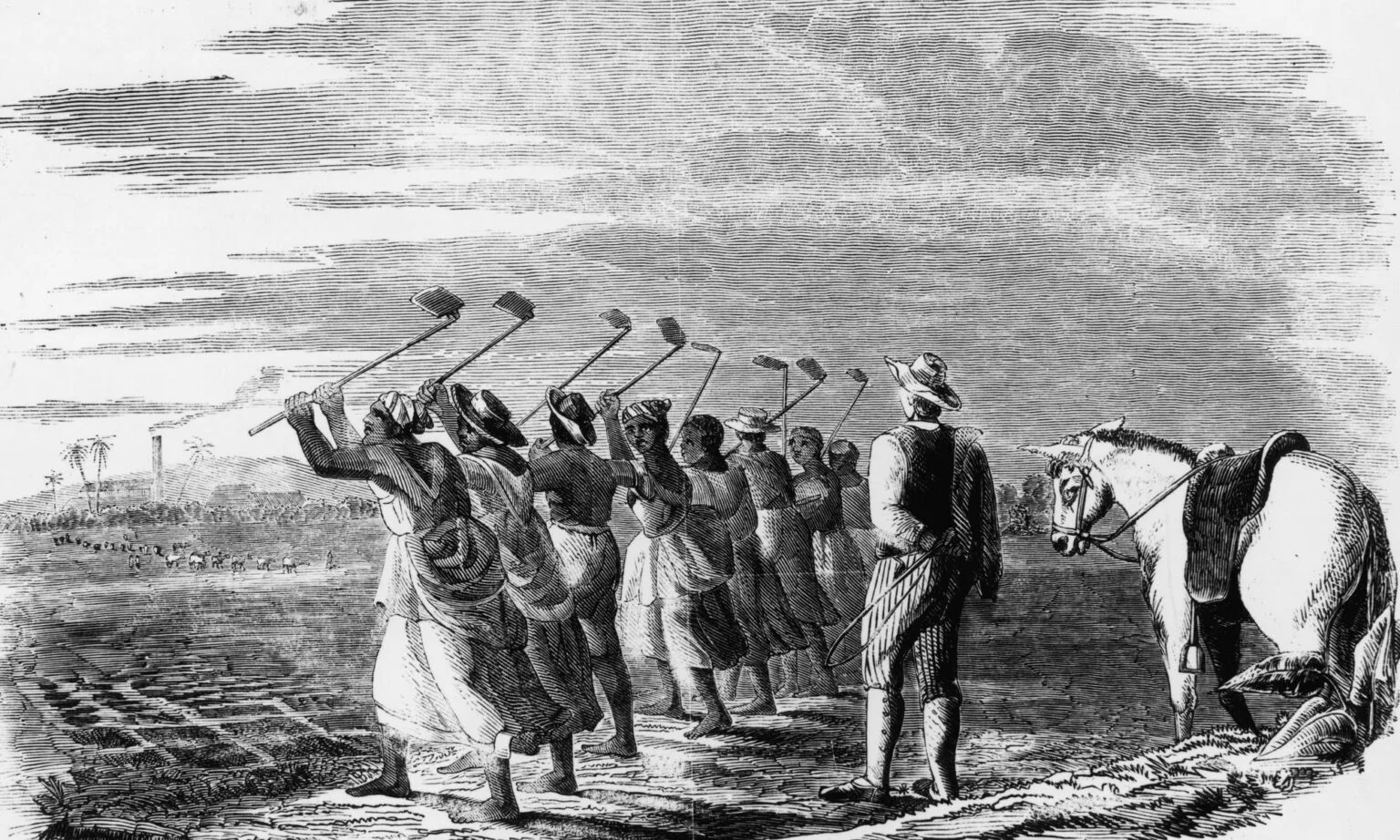

Most of the slaves on British ships were taken to British colonies in the Caribbean. Here, they were sold and forced to work, mostly on sugar or sometimes tobacco or cotton plantations, until they died. The Caribbean planters worked the enslaved so harshly that – unlike slaves in the US or Brazil – many had no children. As a result, the workforce had to be replenished by new imports.

The slave trade made ship and plantation owners rich – money that they then brought back home to Britain. They invested it in estates, ports and harbours, warehouses, churches, artworks, banks and in the new factories that were being built towards the end of the 18th century. Many long-standing institutions and organisations can trace some kind of link back to the slave trade. Historical investigations into the legacy of slavery at University College London, into the Universities of Glasgow, Cambridge and Oxford, the National Trust, the Bank of England, the Guardian and even the British monarchy have shown extensive personal wealth and inheritances drawn from slavery and the slave trade.

Native workers ‘cane hoeling’ on a sugar plantation in the West Indies, 1849.

How much of Britain’s wealth was due to slavery has been argued about since slavery was abolished. What is clear is that the colonial trade in sugar from the plantations, the sale of manufactured goods to the Caribbean and the slave trade itself made up a large share of overseas trade. As Robin Blackburn estimates, as much as a quarter of British investment in the second half of the 18th century came from the slave trade (1). The question is, what, if anything, should we do about this history?

A history of reparations

When an individual is wronged, they can take legal action and claim compensation in a civil court. When a nation or a group of people is wronged, compensation is called reparations – the wrong is repaired by a payment.

The history of reparations shows that these are, on the whole, intended to repair the system of private-property ownership. Reparations have generally reflected the interests of the established order overall. They are meant to allow a sense of grievance to be set aside so that normal relations and trade can be re-established. These reparations might be called ‘justice’, but they are often more like realpolitik.

There are many examples of this type of arrangement. In 1815, after the Battle of Waterloo, defeated France was made to pay 700million francs to compensate Britain and its allies. After losing the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, France was again made to pay five billion francs. When the Greeks rose up against Turkish rule in Crete in 1897, they were made to pay four million lira.

The best-known examples of reparations are those made by Germany following the First and Second World Wars. Germany was named the guilty party at the Versailles conference in 1920 and ordered to pay 132 billion gold marks. The debts were onerous, despite being renegotiated downwards, and are considered to be one of the drivers of the rise of fascism in Germany in the years after.

The initial ‘Morgenthau Plan’ for punitive reparations against Germany at the end of the Second World War was shelved out of fear that it would collapse the country. When the Federal Republic of Germany’s economy recovered after the war, reparations were paid to Israel from 1953 onwards – some of which were met in armaments – to the value of $14 billion by 1987.

Germany was not alone in having to pay reparations after the war – Japan was made to recompense the Netherlands for the wartime occupation of Indonesia, which had been a Dutch colony at the time. But Germany was allowed to be selective in its commitment to the ‘justice’ of reparations. It paid reparations to Yugoslavia, Greece and Czechoslovakia, but only compensated Polish citizens who were victims of slave labour. Under pressure from the Soviet Union, Poland’s then Communist rulers relinquished other claims to reparations in an attempt to free East Germany, a Soviet satellite, from any liabilities. (In 2022, the German government dismissed Poland’s new claims for reparations against Germany.) Germany’s selective compensation to those nations it occupied in the war was more to do with restoring its reputation than with righting wrongs. Apologies and reparations were how the West German government clawed its way back to respectability on the international stage.

Reparations and slavery

Today, many campaigners have called for Britain and America to pay reparations to the descendants of slaves. They often argue that reparations are a tool of anti-racism. Indeed, a 2019 UN report stated that, in order to achieve racial justice, nations that benefited from the slave trade should ‘make amends for centuries of violence and discrimination… including through formal acknowledgment and apologies, truth-telling processes and reparations in various forms’.

But this idea that reparations can achieve racial justice is certainly not borne out by the history of slavery and reparations.

In the American War of Independence, British authorities undermined the colonists by encouraging slaves to rebel against their masters and join British forces. They were even promised their freedom if they did so. At the peace negotiations in Paris, American negotiators asked for compensation for the loss of their slaves but were refused.

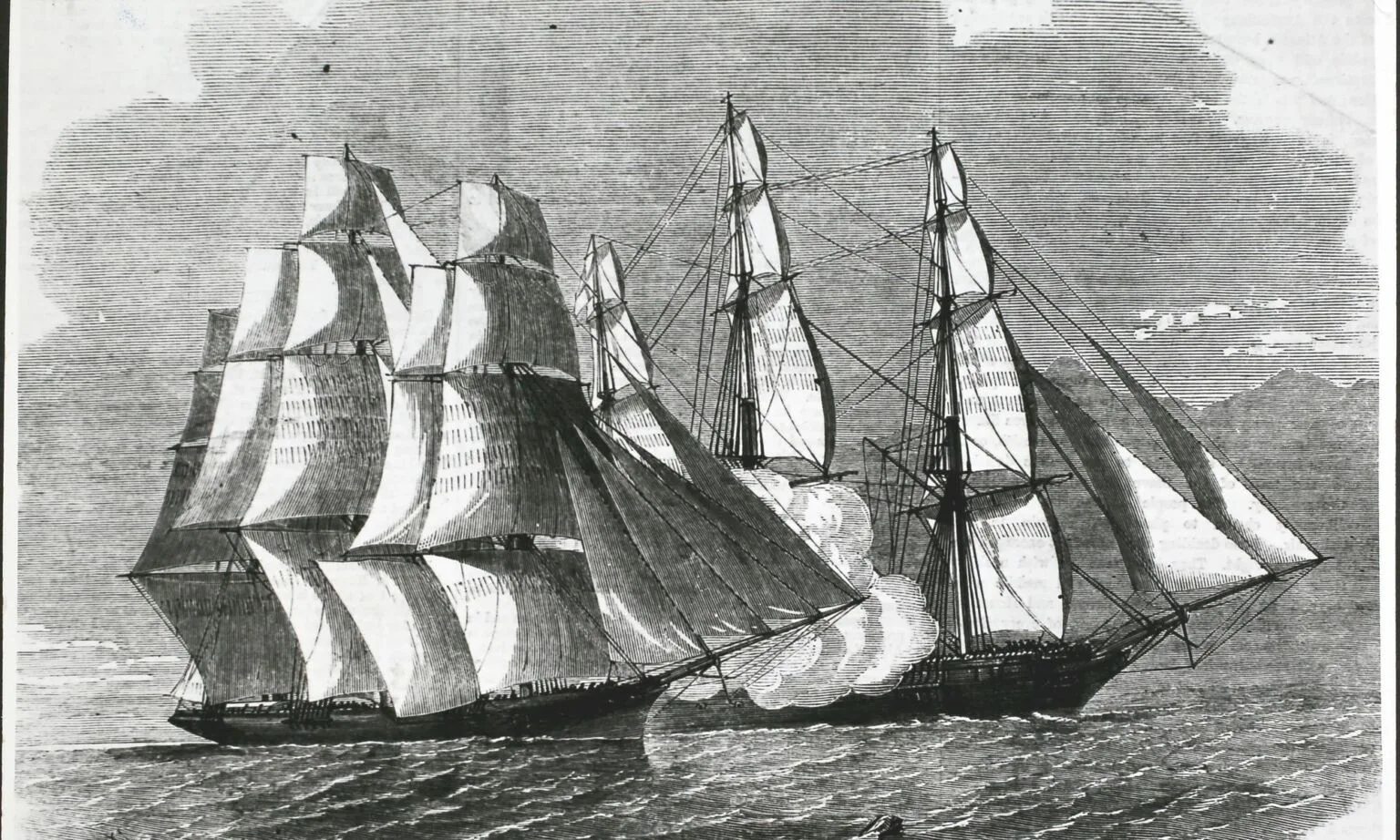

In the Napoleonic Wars, the British banned the slave trade and used the British navy to enforce the ban across the Atlantic. They did this for two reasons. The first was that a strong anti-slavery movement had taken the country by storm, gathering millions of signatures on anti-slave-trade petitions. The second was that enforcing the ban would give the navy the right to search French and American ships crossing the Atlantic.

The British discovered that enforcing the ban on the slave trade not only gave them authority over international shipping. It also gave them a way to dictate terms to their great-power rivals. Just as slavery was important to Britain in the 18th century, anti-slavery became important to its power projection in the 19th century.

British liberals were not the only force fighting against slavery – the slaves themselves were in revolt against their conditions, too. They went furthest in Saint-Domingue, a French colony. Taking advantage of the revolution in France, the enslaved rose up and formed their own government under the leadership of Toussaint L’Ouverture. They named their country Haiti. In 1825, the French government demanded reparations of 150million francs from Haiti for the loss of property. To buy international acceptance from the Great Powers, Haiti agreed to the reparations, which were not paid off until 1947, coming to $21 billion including interest.

In 1830, the anti-slavery movement had turned its attention from the Middle Passage to the slaves on British-owned plantations in the West Indies, where many had risen up against their masters. By that time, the plantations were making less money and most were in debt. Things were so bad that a contemporary pro-slavery pamphlet asked sarcastically why the anti-slavery merchants did not just buy the slaves their freedom (2). Anti-slavery leaders William Wilberforce and Thomas Fowell Buxton took these jibes seriously, and proposed a law to buy the slaves their freedom by raising £20million (about one-fifth of Britain’s annual GDP at the time) in a loan to compensate the slave owners for their loss of property.

The £20million did not even get to the West Indies. Most of it was used to pay off the debts planters owed to banks and creditors in England. Planters tended to be absentee owners, spending their money in the ‘mother country’. Almost overnight, the West Indies, which had enjoyed great wealth during the 18th century, was turned into the poorest corner of the British Empire.

Looking back, people are amazed that abolition entitled the slave owners to compensation, not the slaves. But it was simply a reflection of the parliamentary arithmetic in the Reform Parliament of 1832. There was a majority for emancipation, but this was countered by a strong prejudice against the expropriation of property. That is what reparations looked like in practice.

However, this did not settle the question of reparations. It was raised again and again. And every time that the British government offered to make amends for what it had done, the reparations seemed to work in the empire’s interests rather than those of the enslaved.

Indeed, in 1847, then foreign secretary Lord Palmerston said, ‘This country does owe a great debt of reparation to Africa’ (3). Palmerston was speaking in favour of funding the West Africa Squadron of the British navy. Between 1807 and 1860, the navy seized 1,600 ships and liberated some 150,000 enslaved Africans. He said: ‘It will be some atonement to remember that if England was among the first to commit the sin, England also led the way in a noble and generous crusade – that we not only abolished our own slave trade, but we also emancipated our own slaves.’

HMS Brisk during attempts by Great Britain to eradicate the slave trade in Africa, 1860.

The West Africa Squadron was also very useful to Britain. After the wars with the American colonists and Napoleon were over, the campaign against slavery became part of British power projection in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Britain demanded not just naval superiority, but also forced its allies to sign up to anti-slavery treaties and to take part in ‘Mixed Commission Courts’ to punish the slave traders.

Freeing Africa by colonising it

The West Africa Squadron did not just take on Spanish, French and American slave traders; it also waged war against African states that were compromised by the slave trade. Britain invaded the Asante in 1824, 1854 and 1873, bombarding Lagos in 1851. In the 1860s, missionary David Livingstone’s reports of the damage done to East Africa by Arab slave traders stirred up a new moral campaign in Britain to rid Africa of slavery.

The campaign against Arab slavery was therefore a self-conscious attempt to cleanse the stain of European slavery. Cardinal Manning told an Anti-Slavery Society meeting in 1888 that the Mahometan slave trade was ‘a thousand times worse than anything in the West’ (4).

All the European powers were now united on the need to free Africa of slavery – so much so that they decided to colonise it. International conferences in Berlin (1884-85) and Brussels (1889-90) were called to deal with the ‘Arab slave trade’. In the Brussels conference, a great map of Africa was hanging above the delegates. It was supposed to show the routes of the slave-trade caravans. Instead, the European delegates used it to divide the continent between them.

The colonisation of Africa may have resulted in the exploitation of Africans and the plunder of their land. But it was carried out in the name of saving Africans. Britain’s then prime minister, Lord Cecil, said that ‘we are most concerned, strange to say’ with ‘the interests not of Europe, but of Africa’ (5).

By 1900, the whole African continent, apart from Liberia and Ethiopia, was governed by Europeans. Though they said they were there to abolish slavery, they were now in charge of making the native peasantry work to create wealth. Often that meant forced labour in compounds or on native reservations. An East African pamphlet of 1944, titled Buganda Nyafe (Buganda, Our Mother), charged that ‘the slave trade was abolished in one way and then reintroduced in another’ (6).

The fight for independence

Even when Africans were demanding their freedom, the British decided that they were not yet done with improving their condition. In 1938, Lord Hailey argued in his African Survey that Britain’s obligations to the welfare of colonised peoples meant it would be wrong to allow their independence (7). This formed the basis of the Colonial Development and Welfare Acts of 1940 and 1945.

Not everyone agreed. The idea that colonists really only had the best wishes of the colonised at heart didn’t wash with many of those who were subjected to their ‘welfare’ acts. The fact that the British had adopted a caretaking role to justify denying independence was seen as demeaning and insulting – the suggestion being that without being colonised these countries would fail to progress.

Ghanaian prime minister Kwame Nkrumah was sceptical: ‘The less developed world will not become more developed through the goodwill or generosity of the developed powers.’ (8)

Philosopher and anti-colonial activist Frantz Fanon saw the case for change with an eye on the future, not on the injuries of the past. ‘I am not a prisoner of history’, he wrote, ‘I should not seek there for my destiny’. ‘Am I going to ask the contemporary white man to answer for the slave ships of the 17th century’, Fanon asked? ‘I am not the slave of the slavery that dehumanised my ancestors’, he answered (9).

What Fanon and Nkrumah were saying was that asking for compensation or help was disempowering. It stops you from working for what you need in the here and now. The Trinidadian historian and activist CLR James said something similar. He wrote of West Indians ‘determined to discover themselves, but without hatred or malice against the foreigner, even the bitter imperialist past’ (10).

It was hope for the future that persuaded these Third World revolutionaries not to dwell on the past. Independence, not dependency upon the West, was their goal.

Reparations today

The modern claim for reparations is a product of defeatism. Among black activists, the call for reparations is a sign of their low horizons. Instead of fighting for independence and freedom, they are demanding compensation for past wrongs.

Hilary Beckles puts this demand in militant terms. In Britain’s Black Debt (2013), he argues that Britain must apologise for its crimes and make reparations to the descendants of slaves in the Caribbean and Africa.

Some propose more research and education on Britain’s slave past as an intermediate goal. Research and education are good, of course, but the argument that Britain is in denial about its slave-trading past does not stand up. On the contrary, universities, schools and museums are falling over themselves to do research and to educate people about slavery.

The likes of Beckles are doing down the black community in Britain and the Caribbean. They paint Afro-Caribbeans as victims of the past, not authors of their own future. Beckles insists he is not asking for a handout, even while he is clearly asking for a handout. The argument for reparations puts all the onus on the British government to act and diminishes the agency of Afro-Caribbeans.

Just as craven are the establishment figures who seek moral authority by apologising for the past. They are leaders who doubt their authority to lead and hope that acknowledging guilt will make them seem more human. From King Charles III to the publishers of the Guardian, they fall over themselves to admit to crimes they did not commit. Black impotence and white guilt make a heady mixture.

What history clearly shows is that reparations have always represented the interests of the compensating power, not the compensated. Historical guilt is a luxury only the very rich can afford.

James Heartfield writes and lectures on British history and politics. His latest book is Britain’s Empires: A History, 1600-2020.

This essay was originally published by the Academy of Ideas as part of its Letters on Liberty series. Subscribe to the Academy of Ideas Substack for more.

(1) The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492-1800, by Robin Blackburn, (Verso Books, 2010), p542

(2) A Speedy End to Slavery in the West Indian Colonies, by TS Winn, (London, 1827)

(3) Hansard House of Commons Debate, 9 July 1847, vol 94, §129

(4) The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, 1838–1956: A History, by James Heartfield, (Oxford University Press, 2017)

(5) The Anti-Slavery Reporter, December 1889, pg 237

(6) Quoted in Colonial Wars and the Politics of Third World Nationalism, by Frank Furedi, (IB Tauris, 1994), p33

(7) An African Survey, by Lord Hailey, Oxford University Press, 1938

(8) Worldmaking After Empire, by Adom Getachew, Princeton, 2019, p150

(9) Black Skin, White Masks, by Frantz Fanon, Pluto, 1986, pp229-30

(10) The Black Jacobins: Toussaint Louverture and the San Domingo Revolution, by CLR James, (Vintage Books, 1962), ‘Afterword’

Pictures by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.