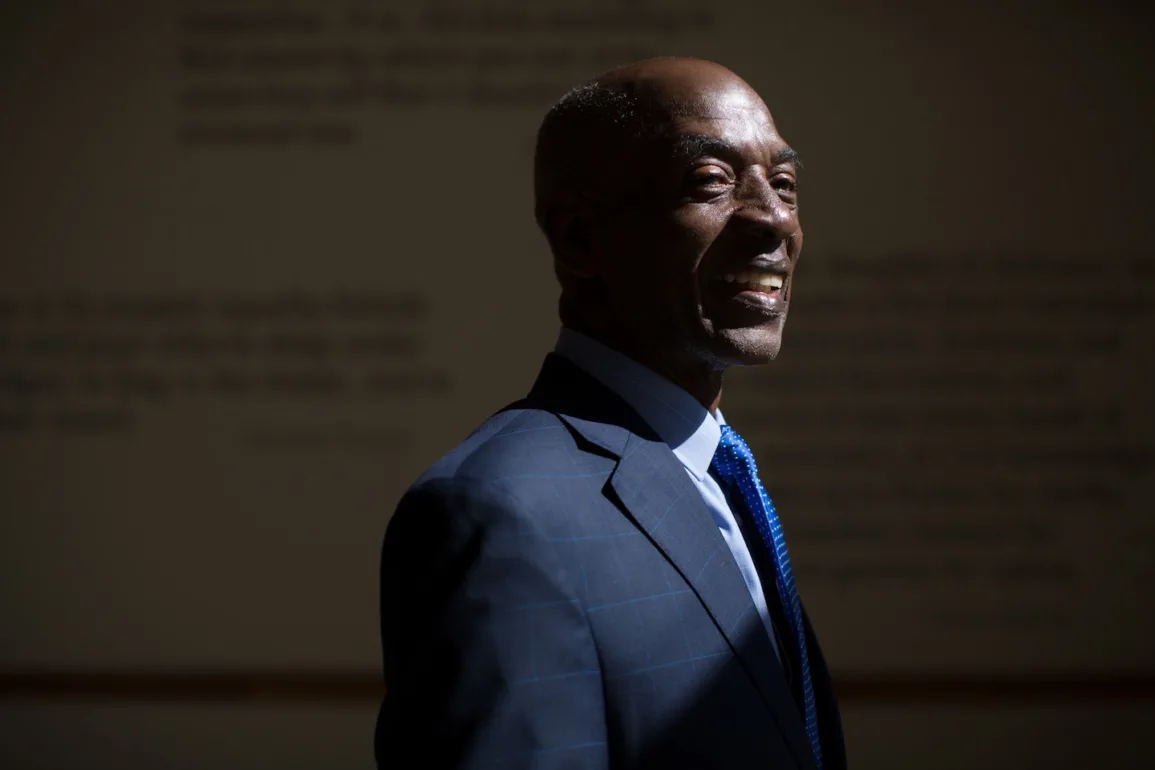

Charles J. Ogletree Jr., a Harvard Law professor who championed civil rights in the classroom as well as the courtroom, notably through his resolute but unsuccessful campaigns to obtain reparations for the survivors of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre and the descendants of enslaved people, died Aug. 4 at 70.

His death was announced by Harvard Law School, which did not say where or how he died. Mr. Ogletree revealed in 2016 that he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Mr. Ogletree, affectionately known as Tree, rose from an impoverished childhood in California’s Central Valley to become a celebrated public defender in Washington, a leading legal theorist at Harvard Law School, and an attorney for such high-profile clients as Mafia leader John A. Gotti, rapper Tupac Shakur and Anita Hill when she accused U.S. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment.

At Harvard, where Mr. Ogletree received a law degree in 1978 and began teaching in 1984, he brought a more clinical focus to a law school long known for its emphasis on legal theory. He also brought a degree of diversity to a faculty that was overwhelmingly White.

Mr. Ogletree mentored students including Barack and Michelle Obama, espousing an understanding of the law as “an instrument for social and political change” and “a tool to empower the dispossessed and disenfranchised.”

To that end, he organized Harvard’s Criminal Justice Institute, in which students represent poor clients in the Boston area. He also led a “Saturday school” program geared toward minority students seeking additional training in the intricacies of tort law or civil procedure, and established the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice, a center for public policy and legal advocacy named for the civil rights lawyer who taught Thurgood Marshall, the first Black Supreme Court justice, and Oliver Hill, who helped overturn legal segregation in Virginia.

“If you mention the name ‘Ogletree,’ I don’t think the word ‘weakness’ comes into anyone’s mind,” fellow Harvard Law professor Alan Dershowitz told the Boston Globe in 1995. “Here’s a guy who could be anything he wants. He could be a judge, he could be dean, he could be a justice on the Supreme Court. He’s a man for all seasons.”

Mr. Ogletree came to national prominence in the late 1980s as a moderator of “Ethics in America,” a 10-part PBS program in which law professors posed hypothetical scenarios to politicians, journalists and other public figures. He later was a legal commentator, accurately predicting an acquittal in the O.J. Simpson murder case, and wrote and edited books on capital punishment, life without parole and police conduct in minority communities.

As a lawyer, his clients included Desiree Washington, a Miss Black America contestant who was raped by boxer Mike Tyson. (Tyson was convicted in 1992 and sentenced to six years in prison.) Mr. Ogletree also represented Shakur in several cases before the rapper was fatally shot in 1996, and served on Gotti’s legal team when the mobster pleaded guilty to racketeering charges in 1999.

But he was most closely linked to Hill, a lawyer and academic who in 1991 accused Thomas of sexually harassing her when they worked together at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Mr. Ogletree was up for tenure when she invited him to join her legal team. “He had a lot on his plate, and being involved, on my behalf, in a sensational public hearing may have made some faculty uneasy,” Hill told the Harvard Gazette, a university publication, in 2017. “He really had his job and his career on the line, but Charles agreed.”

As a senior lawyer on Hill’s legal team, Mr. Ogletree suggested she hold a news conference announcing the results of a polygraph test, in which she was found to have answered truthfully while recalling that Thomas spoke to her about pornography, sex acts and his physical endowment.

The news conference, and three days of televised congressional hearings, galvanized a national debate over sexual harassment but failed to block the confirmation of Thomas, who denied the allegations.

Mr. Ogletree’s work often centered on the intersection of race, class and criminal justice. A self-described “Brown baby,” he credited much of his professional success to opportunities created in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which declared segregated public schools unconstitutional, even as he insisted that the courts — and the country as a whole — had not gone far enough in addressing racial discrimination.

His efforts to combat inequality culminated in the Reparations Coordinating Committee, a group of Black lawyers, intellectuals, activists and scholars convened after the publication of “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” a 2000 bestseller by lawyer Randall Robinson, who estimated unpaid wages to enslaved people at $1.4 trillion. Another estimate, cited in Harper’s magazine, put the total at $97 trillion.

Mr. Ogletree, the committee’s co-chair, argued that reparations for slavery were a moral necessity, and called for money to be placed into a fund benefiting “the bottom-stuck,” his term for Black Americans who never benefited from integration.

Working with lawyers including Johnnie L. Cochran Jr., he pursued an array of reparations claims, including a 2003 lawsuit on behalf of the 150 survivors and nearly 200 descendants of the victims of the Tulsa massacre.

The killings, sometimes described as a race riot, were triggered by the arrest of a Black teenage shoe shiner who had stepped into an elevator with a White elevator operator, who then screamed; according to one popular account, the teenager had stepped on the back of her shoe. Much of Tulsa’s prosperous Black community was subsequently destroyed, with 40 blocks razed, more than 10,000 people left homeless and some 300 killed.

An Oklahoma state commission recommended reparations for the massacre’s victims, but the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case in 2005, leaving in place a lower court’s ruling that too much time had passed since the event. Mr. Ogletree was similarly unsuccessful in a 2002 lawsuit, filed on behalf of the descendants of enslaved people, which argued that companies including Lehman Brothers, Aetna and R.J. Reynolds had profited from slavery.

Nonetheless, he and Robinson “raised public awareness about the present effects of historic injustices suffered by Blacks, and urged all Americans to reckon with slavery,” said Tomiko Brown-Nagin, a Harvard Law colleague and then-director of the Houston Institute, in a 2019 interview.

Mr. Ogletree remained optimistic that reparations would eventually come to pass. In the meantime, he sought a more immediate response to the pain he and his forebearers had felt for generations. He had tried to research his family history, he said, but found it difficult to trace his lineage through long years of slavery and bondage.

“There are no grave markers, no birth records. Just a void that is palpable,” he told the Harvard Law Bulletin in 2001. “If I could take the step to fill that void, to me that would be important. There would be no anger. There would just be a sense of closure.”

Early political activism

The oldest of six children, Charles James Ogletree Jr. was born in Merced, Calif., on Dec. 31, 1952. Fishing trips with his grandfather were a respite from a home life in which his parents, both farmworkers, frequently fought. They eventually divorced.

Mr. Ogletree immersed himself in political activism as a student at Stanford University, attending Black Panther events and editing a Black student newspaper. He also sat in on the trial of scholar and activist Angela Davis, who was ultimately cleared of charges that she had participated in a 1970 shootout at the courthouse in nearby Marin County.

The trial, especially the intricate defense strategy of Davis’s attorney, Leo Branton Jr., inspired Mr. Ogletree to pursue a legal career. He graduated from Stanford in three years, receiving a bachelor’s degree in 1974, and earned a master’s degree from the school the next year.

While at Harvard Law, he was elected president of the Black American Law Students Association (now the National Black Law Students Association). He joined the D.C. Public Defender Service after graduating and resigned in 1985, after being passed over as director.

Mr. Ogletree worked in private practice before joining Harvard full-time in 1989. He also served as chairman of the Southern Center for Human Rights and was board chairman of the University of the District of Columbia.

He married Pamela Barnes, a Stanford classmate who went on to lead Children’s Services of Roxbury, a Massachusetts nonprofit, in 1975. In addition to his wife, survivors include two children, Charles Ogletree III and Rashida Ogletree, and a number of grandchildren. Additional details on survivors were not immediately available.

In 2004, Mr. Ogletree published “All Deliberate Speed: Reflections on the First Half-Century of Brown v. Board of Education,” which mixed elements of history and memoir. After several paragraphs were found to have been plagiarized from a work by legal scholar Jack Balkin, Mr. Ogletree issued an apology, saying that two research assistants had accidentally inserted the passage into the manuscript without attribution.

His other books included “The Presumption of Guilt” (2010), written after Henry Louis Gates Jr., a Black filmmaker, scholar and cultural critic based at Harvard, was arrested at his home when a 911 caller mistook him for a burglar.

The arrest sparked a national debate over race and policing, with President Barack Obama remarking that the police “acted stupidly.” The incident echoed concerns Mr. Ogletree raised more than a decade earlier, when he told the Globe that he feared for his children’s safety when they left the house. Even his teenage daughter was considered “a psychological threat” when she went trick-or-treating, he said.

“I’ve got to tell them it’s going to be all right, it’s going to get better,” he added, acknowledging that he played the part of the “eternal optimist,” even in the face of contrary evidence. “If I’m giving up on the system, what chance do they have? I’m not going to give up. … That’s not going to happen.”