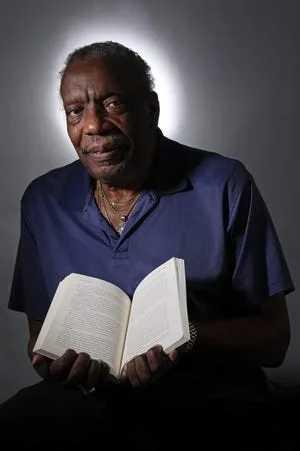

In his autobiography, out this month, Nat Glover ponders the twists and turns in his eight decades of life, the obstacles that became opportunities, failures that became successes and the people — white and Black — who seemed to see something in him, something that would propel him from a shotgun house on Minnie Street to Jacksonville’s highest corridors of power.

He also writes of the need to stand up to systemic racism and warns of the dangers of today’s toxic, partisan political environment, which seems intent, he says, on erasing the progress that’s been made.

That frankness hasn’t always been there: As a Black man growing up in the segregated South, he long had to carefully measure his words to get where he wanted to be.

“I had to suppress my anger,” he writes, “in favor of calculation and strategy to accomplish what I did.”

During a recent interview with the Times-Union, he’s asked does he feel that he’s now able to speak more freely, after all he’s accomplished, at 80 years old?

‘A monumental type of glory’:Edward Waters University becomes a reality

A big, big laugh comes out of him as he replied, “I know you’re implying ‘You ain’t got but a few more days to live!’”

He laughs some more, but as his chuckles wind down, he gets to what he sees as the truth. “I’m at a place now,” he says, “where I feel like a lot of people look to me to say something.”

That’s a thread that runs through “Striving for Justice: A Black Sheriff in the Deep South,” where he writes of the “responsibility” he feels to lead, to share his story.

He grew up poor in Jacksonville, went to Edward Waters College on a football scholarship, then joined the Jacksonville Police Department, which later became the Sheriff’s Office. He moved up to detective, then chief of services, before running for sheriff. He won with 55% of the vote in 1995, the first Black sheriff of a large city elected in Florida since Reconstruction, then went on to serve a second term.

He got national recognition for his community policing policies and decisions to ban chokeholds and to display officers’ names on their vehicles. In 2021 he was inducted into the Florida Law Enforcement Officers Hall of Fame.

He ran for Jacksonville mayor in 2003 but lost in a tough contest to John Peyton, who then asked him, to Glover’s surprise, to serve as co-chair of his transition team. Glover readily agreed. He later became president of Edward Waters College, his alma mater, stepping down in 2017 after seven years.

Ax Handle Saturday

In “Striving for Justice,” he tells how his future was shaped by two events in 1960 when he was working as a teenage dishwasher at Morrison’s Cafeteria downtown.

In one, he was stopped by police after he left work. Officers found two of the restaurant’s cloth napkins in his pocket, and though he told them dishwashers were allowed to use them to wipe their faces during work, he was arrested and charged with petty larceny. His father had received advice that it would be better for him to plead guilty, so he did.

Then came Ax Handle Saturday, where whites incensed by recent civil rights demonstrations rampaged through downtown with ax handles and baseball bats, beating and threatening Black people.

After leaving work at Morrison’s, Glover was surrounded by men who taunted him and jabbed him with bats and ax handles. Glover writes that a nearby white police officer just watched, and after Glover pleaded for help, said only, “Boy, you better get out of here before they kill you.”

He did, running a mile to his house, not looking back. At home, he wept in shame, feeling like a coward for running away.

In the Times-Union interview, he recalled what he did next: “I said that day that I would never run away from another fight. Never. I would rather die first. That affected my life in a way that, if I don’t do something that I feel like I should have done, then I find it hard to live with.”

At that point, he brought up a poem he had learned at New Stanton High School. It’s called “Myself” by Edgar Guest. Placing one hand over his heart, he recited the first few lines by memory:

I have to live with myself and so

I want to be fit for myself to know.

I want to be able as days go by,

always to look myself straight in the eye;

I don’t want to stand with the setting sun

and hate myself for the things I have done.

Glover paused. “That has always stuck with me,” he said.

‘A divine journey’

Two threads run through the story Glover tells in his book. One is the rise of a young man born in poverty who was helped along the way by those who saw qualities of leadership in him. Among them was the coach at Edward Waters; a Black police officer who introduced him to white Mayor Lou Ritter, who pulled strings to allow him to take the police entrance exam despite his conviction for petty larceny; colleagues; and political donors and advisers.

He said that support gave him the confidence that he could step up to the responsibilities placed before him.

Nat Glover’s teachable moment:It wasn’t all smooth sailing

“It was a divine journey,” he said, “and when you think of me coming from this environment and having things happen to me, and having people step up from unlikely positions and saying, ‘I’ll help you’ — it was like my job was to have the faith to step out, the courage to step out, the vision to step out. Not having a road map, but as I embarked on the journey, all along the journey, every time I got to a crossroad, there was someone there to say, ‘Go this way.’”

The other thread in the book is how often poor and disenfranchised young people become enmeshed in the criminal justice system, never meeting the potential they might have.

“’Striving for Justice,’ the essence of the title, had to do with that, how so many poor kids don’t get the breaks,” Glover said.

He stressed that most people in the criminal justice system are honorable, trying to do their best. But not all. “Implicit bias” and even outright racism are still too often seen.

“The system is not fair-minded, too often imposing far harsher sentences on people of color than on white Americans who commit identical crimes,” he writes.

Nat Glover: A call to reform the criminal justice system

His two teenage run-ins with police officers were, he is sure, evidence of a criminal justice system that was weighted against Blacks. Those encounters, though, only served to set him on his path to law enforcement.

“That was my main reason for wanting to become a detective,” he said. “So I would have that kind of authority, that kind of ability to influence people’s lives.”

‘We are better than this’

Opportunities for Black people today are immeasurably improved than they were when he was growing up, Glover said, going down a long list of Black leaders that the city has had across political, law enforcement, business, civic and charitable groups.

That’s a story the city should be talking about, he said. Boasting about even.

“In Jacksonville, we’ve got an inclusive environment where we’ve been working together for years,” he said. “And there’s no doubt about it, there’s a lot of good white folk. That’s the reason I’m sitting here, and that’s the reason I’m so guarded — we don’t want to go back.”

He worries those gains could be chipped away.

“We are slipping back, but here’s my unique perspective on the reason we’re slipping back: It’s because we’ve come so far, and we’re doing so well as it relates to coming together.”

Does that scare some people? he’s asked.

“It’s not scaring people,” he replied. “It’s terrifying them, terrifying them, to see the kind of change that’s happening.”

In his book, Glover looks at the nation as a whole, pointing to the “rancid, downward spiral of partisanship, discord, greed and selfishness, this denial of science and fact-based reality,” and noting the rise of “fear-based ideologies.”

He proclaimed himself “appalled” at “extremists in political office and in dark corners of the media” who tried to discourage vaccinations during the COVID-19 pandemic. He said he was “sickened” by the events of Jan. 6, 2021, and dismayed at attempts to reverse the legitimate outcomes of elections and the rollbacks of voting rights in state after state.

It’s all about speaking out for what he believes is right, he said. And that’s why he agreed to make a TV ad criticizing the negative advertising that the campaign of Republican Daniel Davis — whom he calls a “very, very good friend” — ran against Democrat Donna Deegan, the eventual winner of this year’s race for Jacksonville mayor and who later appointed Glover to her transition team.

“I just couldn’t hold my tongue,” he said.

Looking straight into the camera, he said in the ad that he doesn’t endorse political candidates but “must speak up” at this time: “I will not remain quiet and allow this city to go back to the us versus them era.”

In 2023:Mayor-elect Donna Deegan names big-name advisers to lead her transition. Who are they?

He’s a Democrat, he said, but he’s worked with Republicans throughout his time in public office, saying he figured it was the right thing to do since Democrats, Republicans and independents were the ones who helped make him sheriff.

The city, and the country, need to put divisiveness aside, Glover said. Indeed, that’s how he ends his book, with these words: “We are better than this,” he wrote. “Let’s prove it to our children and grandchildren.”