The theft of land, displacement and erasure has tormented Black people since emancipation. After the disbursement of land to the formerly enslaved was revoked following President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, the call for reparations has had a steady drumbeat. But since the California Reparations Task Force delivered its landmark 1,200-page report in June, the drumbeat has never been louder.

The report has 115 recommendations for reparative measures, including restitution for racially motivated takings of homes.

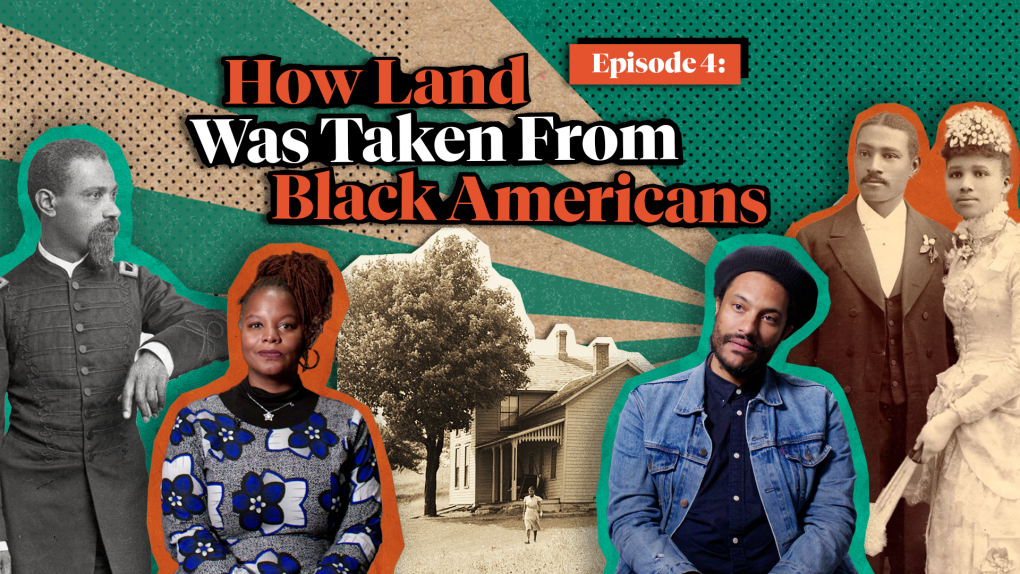

In the fourth episode of our video series on reparations, we explore the stories of thriving Black communities — Bruce’s Beach, the town of Allensworth, San Francisco’s Fillmore District — that were ravaged by racist policymaking.

“In the beginning of the 20th century, Black people owned 15 million acres of land,” Ward says at the beginning of the video. “By the beginning of the 21st century, 90% of the land was gone. It was taken.”

Millions of acres of Black-owned land was just simply taken. Please remember that the next time a friend, neighbor, colleague or presidential candidate insinuates that Black people aren’t worthy of reparations.

“African Americans in the history of the United States, and within the state of California, have been this kind of available category of persons who can be removed, who can be exploited when it suits the state,” Dr. Jovan Scott Lewis, a member of California’s Reparations Task Force, says in the video.

The denial of Black prosperity is a deliberate feature of the American experiment. In 1862, the federal government passed the Homestead Act, which gave American citizens and soon-to-be citizens the right to claim 160 acres of land as America expanded west. More than 160 million acres were claimed by almost 2 million homesteaders. Enslaved and free Black people were, of course, excluded from the wealth-generating bonanza.

Less than 100 years later, the federal government enacted the G.I. Bill, a program to assist World War II veterans through low-interest mortgages and loans. Black people were once again excluded.

“Between 1935 and the late 1940s, the government issued about $120 billion in low-interest housing assistance loans. Ninety-eight percent of those loans went to white people,” Donald K. Tamaki, a member of California’s Reparations Task Force, told Manjula Varghese, my colleague, who is the lead producer of the video series. “This was the transfer of wealth to help build today’s middle class.”