As a high school baseball star, Denver Hoskins led Kentucky in home runs and was invited to try out for the Cincinnati Reds. But when his father got sick (and later died) from black lung, a disease caused by inhaling mineral dust, the younger Mr. Hoskins gave up his Division I college scholarship offer to support his family. Following in his father’s footsteps, he went to work as a coal miner. By the age of 44, Mr. Hoskins was diagnosed with his own case of the most severe form of black lung. He now breathes from an oxygen tank at night and watches his son’s batting practice from the sidelines.

I met Mr. Hoskins in St. Charles, Va., a former coal mining hub in Lee County, the place immortalized in Barbara Kingsolver’s 2022 novel “Demon Copperhead.” Though the town has shrunk to a population of 72, coal miners from across Appalachia — including Virginia, Kentucky, West Virginia and Tennessee — are now flocking there to seek care at Stone Mountain Health Services, a community health clinic that includes the nation’s largest black lung clinic, where I serve as black lung medical director. Last year we cared for over 500 former coal miners with the most severe form of black lung, a record for the clinic’s 32-year history.

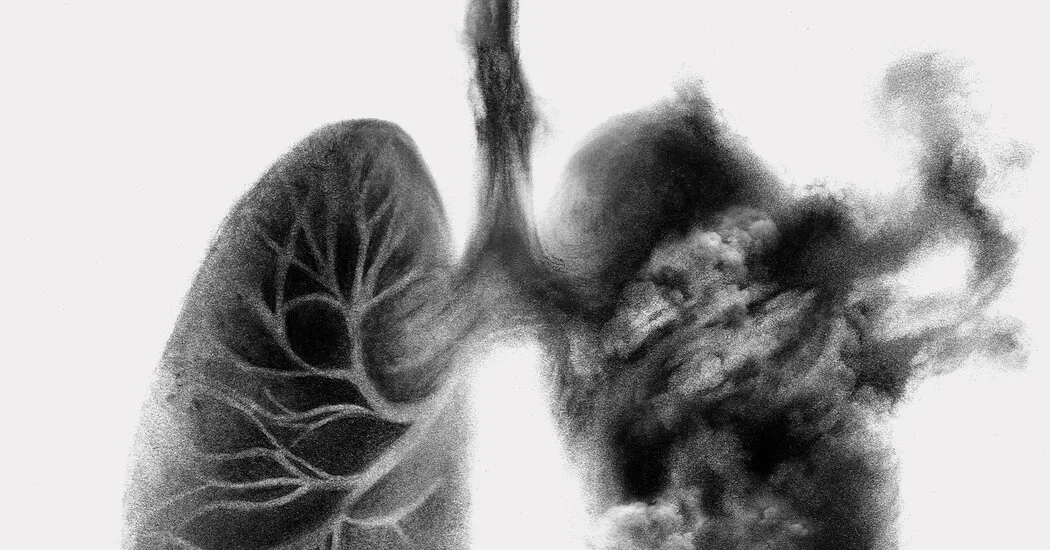

By the end of the last century, thanks, in part, to federal safety standards, severe black lung had nearly been eliminated. But with changes in technology and conditions in coal mines in central Appalachia, cases of severe black lung disease are back to the highest level in decades after the last major study, in 2018. As of that year, more than one-fifth of experienced Appalachian miners have black lung.

When I see these patients, I can prescribe oxygen and enroll them in exercise programs, but there are no treatment options. The disease often progresses to respiratory failure and, in many cases, death. Nearly all of those deaths are premature, with the most recent estimates from 2018 suggesting a loss of roughly 8 to 13 years of life for those who die with black lung, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study.

Why has this 100 percent preventable disease come roaring back? Because the government’s safety standards — which rely, in part, on coal companies to police themselves — haven’t kept up with the latest working conditions in mines and don’t sufficiently limit exposure to the biggest hazard of all: silica.

After years of advocacy by workers, unions, lawyers, nonprofits, health professionals and widows of black lung victims, the Department of Labor’s Mine Safety and Health Administration finally released a proposed rule this summer that would reduce the allowable silica dust levels to the same threshold as every other U.S. industry. But even those regulations remain woefully insufficient and unspecific. It’s urgent that they be strengthened before being finalized this November. It’s not just coal workers who stand to benefit: Metal, sand, stone and gravel miners are also at risk. All miners need protection.

Silica dust is found in higher concentrations in Appalachian coal mines than in any other U.S. mines. That’s because as the more accessible, larger coal seams have been exploited, miners have been sent to small seams buried deeper inside mountains. Getting to these seams and extracting the coal often means pulverizing huge quantities of rock containing silica.

John Robinson spent over two years tunneling through 3,200 feet of rock using drills and dynamite to reach coal in Dickenson County, Va., a few miles from the border with Kentucky. He was diagnosed at Stone Mountain with the most severe form of black lung at age 47. Like Mr. Hoskins, Mr. Robinson also needs supplemental oxygen to survive.

The proposed rule would protect miners only during “typical mining activities,” which might not be interpreted to include mine construction, when workers like Mr. Robinson are at exceptionally high risk of high silica dust exposure. Instead of using vague language about typical activities, the Mine Safety and Health Administration needs to specifically require periodic testing during all phases of a mine’s construction and operation.

The proposal also states that when silica levels are dangerously high, miners must use respirators — not N95s but the kinds of masks that cover most of the face with rubber and plastic — until employers can figure out how to fix the dust problem. Any miner will tell you that wearing a respirator in a hot, loud, confined space while sweating through eight-hour or longer shifts of intense manual labor is just not possible. Preventing explosions and keeping walls from caving in requires constant communication in a way that’s difficult when everyone’s wearing those masks. The real solution is for mining companies to ventilate the mines or capture or eliminate dust.

Of course, safety regulations are useful only if they’re followed and enforced. If we continue to rely on coal companies to do their own dust sampling without adequate enforcement, black lung deaths will almost certainly continue to climb.

Countless miners at the Stone Mountain clinic have shared stories with me of employers hiding evidence of dangerous conditions. Some patients said they were told by supervisors to put dust monitors in closed lunch pails or to wrap them in coffee filters to make the air quality appear clean. Others were told to place air samplers along passageways where fresh air enters the mine. Miners also described incidents of new and improved ventilation systems being temporarily put in place right before government inspectors came for quarterly visits.

Regulators need to be more explicit about how they will stop these dishonest and dangerous practices. New rules should include unannounced inspections, fines and the suspension of work for mine operators who don’t fix problems. Black lung is incurable but totally preventable. Enforceable regulations that reflect the reality of today’s mining operations can finally break its miserable cycle. The next generation of miners can’t be left to drown in dust.

Drew Harris is the medical director of Stone Mountain Health Services black lung program and an associate professor of pulmonary and critical-care medicine at the University of Virginia.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.