Health disparities between Black and white Richmond residents exist in key areas, according to data aggregated by the Richmond and Henrico Health Districts.

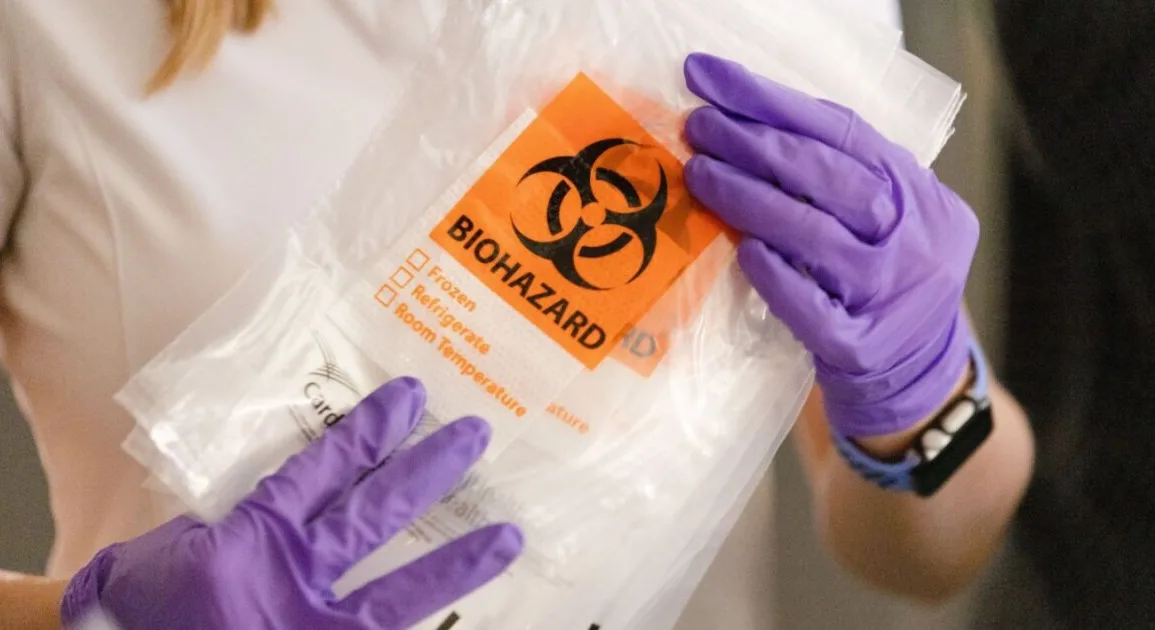

VPM News requested data on the differences in health outcomes by race and income following the announcement of more than $600,000 in Health Equity Fund grants for local organizations to address disparities.

As of the 2020 census, 226,610 people lived in Richmond: 98,140 (43%) were white only, and 91,653 (40%) were Black only. Disproportionate occurrences of illness or health outcomes refer to when a demographic group makes up a higher proportion of a health outcome than its share of the population.

RHHD included a disclaimer with the report it produced for VPM News, saying it was “not meant to be exhaustive of methodologically consistent between the sets of data to the next but rather provide a general summary of the justifications for Health Equity Fund program funding.”

City-level data was not available in some of the seven areas of health disparities that City Council tasked the HEF with addressing, indicating there might be a lack of information as health officials attempt to tackle racial disparities in the city.

“We see large variations within areas that that get masked when you aggregate up to large areas,” said Derek Chapman, interim director of the VCU Center on Society and Health. “Here in Richmond City, we have a 20-year gap in life expectancy at the neighborhood level that you wouldn’t see if you’re just looking at the overall city.”

Those seven areas the Health Equity Fund focuses on addressing?

- COVID-19

- mental and behavioral health

- food access and security

- substance use and recovery

- access to care and health education

- maternal and infant health

- underlying health conditions

Chapman was not surprised by the discrepancies described in some of the data, but did call them “stark and shocking.”

RHHD data indicated that more than half of the cumulative COVID-19 cases in Richmond were among Black people; Latinos were also disproportionally affected. Those groups were also disproportionally represented in hospitalizations and deaths, according to the report.

Total numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths in Virginia are hard to track across all the pandemic. According to the New York Times’ aggregated data, Richmond City had 61,368 total reported cases of COVID and 553 related deaths through March 21, 2023 (when the public health emergency ended in the U.S.). Henrico County saw 91,949 total reported cases and 1,082 deaths for the same period of time.

The state Office of the Chief Medical Examiner said rates of fatal overdoses in Richmond are highest among the Black population, and preliminary data from the OCME said overall rates of opioid overdoses have risen dramatically.

Chapman said there are “broader community factors” that contribute to the use of illegal drugs.

“There are these broader community factors that contribute to some of the reasons why people are doing that,” Chapman said. “When you get into what’s the driving folks to do that, then then you might find that, that these broader socioeconomic factors and availability of jobs, etc., in access to mental health and health care services may be contributors to that as well.”

Some of the starkest disparities were seen in sexually transmitted infections. According to 2021’s Virginia Surveillance HIV Annual Report from the Virginia Department of Health, positive HIV cases, early syphilis diagnoses and new gonorrhea diagnoses in Central Virginia occur disproportionally in the Black, non-Hispanic population.

Data on STIs showed how demographics other than race see different health outcomes. Men who have sex with men are 36% of positive HIV cases in Central Virginia. A study UCLA’s Law School published in 2020 estimated Virginia’s LGBTQ population to be 3.9% — approximately 335,049 people.

Food access is a problem for households without vehicle access, which has historically been indicative of income. The US Department of Agriculture reported 26.2% of those households were more than a half-mile from a supermarket.

“The health differences between neighborhoods are rarely due to a single cause. So it’s kind of a complex web of factors,” said Chapman. “We really have to address multiple factors simultaneously and comprehensively to address this.”

Organizations and individuals can apply for HEF funding until Aug. 13.