In “Shipwrecked,” the historian Jonathan W. White tells the story of an outlaw mariner who worked for the Confederacy and against the Klan.

SHIPWRECKED: A True Civil War Story of Mutinies, Jailbreaks, Blockade-Running, and the Slave Trade, by Jonathan W. White

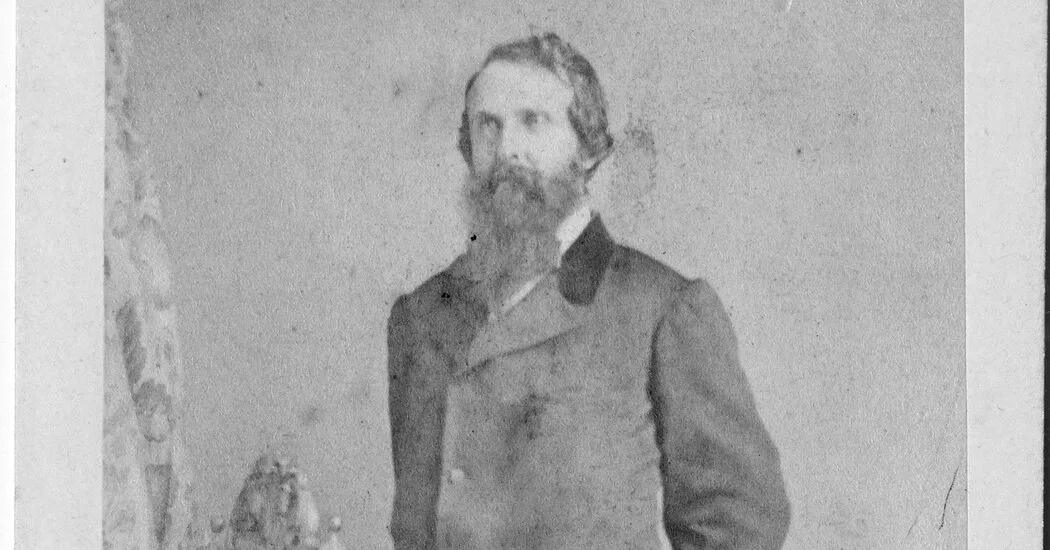

Who was Appleton Oaksmith? One contemporary described him as a “good seaman, & a bold & daring officer.” His enemies, President Abraham Lincoln among them, judged him a scoundrel and a traitor. Oaksmith, writing six years after the Civil War, wasn’t sure what to think: “I look upon myself sometimes with a sort of doubt as to my own identity.”

Jonathan W. White, a prizewinning Civil War historian, finds in Oaksmith’s spectacularly misguided life both a gripping yarn set far from the battlefields and a way to dramatize Lincoln’s determination to eliminate the African slave trade.

As a young seafaring adventurer in the 1850s, Oaksmith armed mercenaries in Nicaragua and joined the liberation movement in Cuba. In 1859, he started a magazine, which foundered and left him bankrupt. As a Tammany Hall Democrat, he attempted to broker a misbegotten agreement between North and South. After Lincoln took office, in 1861, Oaksmith became a shipping agent, outfitting old whaling ships.

His timing couldn’t have been worse. Whaling was in decline, so, it was assumed, the people who bought and fitted whalers were likely slavers. Secret agents prowling the docks found Oaksmith’s vessels suspicious — they were too big, their proposed voyages were too short, there were no towlines or whale irons on board — and Oaksmith, who protested his innocence, was arrested and summarily locked up.

Whiling away the hours in his cell, he wrote poetry by firelight. Then, in 1862, at 34, he made a jailbreak and sailed to colonial Havana, thus earning the lasting enmity of Secretary of State William H. Seward. Because the United States did not have an extradition treaty with Spain, it was all but impossible to bring the fugitive to justice.

By the summer of 1864, Oaksmith had become the captain of a blockade runner, picking up bales of cotton in Galveston, Texas, and sailing them to Cuba. “Driven from the North, I sought refuge in the South,” he explained, “and espoused the Confederate cause.”

At least once, blockaders got close to nabbing Oaksmith. In September 1864, a crew member recalled, as Union sailors boarded Oaksmith’s ship on one side, he “pulled off in a small boat” on the other. Just months before the presidential election, Seward set in motion an attempt to kidnap the outlaw on Cuban soil.

Oaksmith slipped away again and settled in London. He remained in exile, more or less, until he and his formidable mother, Elizabeth Oakes Smith, persuaded President Ulysses S. Grant to pardon him in 1872. Oaksmith eventually moved to North Carolina, where he won election to the Statehouse and served as an anti-Klan independent.

Surprisingly, it is Elizabeth, not Appleton, who is the most vivid character in the book. Her loyalty to her son — a man of “daring courage” who is “gentle-hearted, courteous and imaginative” — is almost matched by her loathing of the “imbecile and tyrannical” Lincoln administration. A women’s rights activist and a popular novelist and lecturer, she kept a detailed diary that chronicled the tumultuous events of the era through her family’s misfortune.

In July 1863, Elizabeth writes that she arrived in New York as the draft riots began. Initially “drunk with excitement,” she cheered on the revolt against the inequitable Conscription Act, then watched with horror as participants began slaughtering African American men and women.

The next day, Jeremiah Hamilton, a wealthy Black acquaintance, happened by in his carriage as she stumbled through the streets. He took her to his house to rest. After Elizabeth departed, a mob invaded the house and Hamilton fled over a fence. Elizabeth ran into him again on the train to Long Island, and she sheltered him and his family for a week at her home in Patchogue.

The astonishing stories in “Shipwrecked” are sometimes weighed down by White’s fealty to comprehensiveness, but in piecing together these lives he offers a fresh perspective on the mess of pitched emotions and politics in a nation at war over slavery.

Dorothy Wickenden is the author of “The Agitators: Three Friends Who Fought for Abolition and Women’s Rights.”

SHIPWRECKED: A True Civil War Story of Mutinies, Jailbreaks, Blockade-Running, and the Slave Trade | By Jonathan W. White | Illustrated | 317 pp. | Rowman & Littlefield Publishers | $29.95