The drive across the high plains of western Kansas can feel and look endless.

Now consider making a 28-mile trek from the end of the rail line to your new home in Nicodemus in 1877, carrying little more than the clothes on your back.

That fall, nearly 350 formerly enslaved people set out from Kentucky to the promised lands of Kansas. Among the first group were Thomas and Zerina Johnson and their adult children.

“They were both pushed out and pulled in,” says LueCreasea Horne, the great-great-great granddaughter of Tom and Zerina. The push to leave, she says, were the Jim Crow laws and the threat of violence in the South.

The pull toward was much greater.

“They were just a little over or 10 years from slavery and took the opportunity to move west and own a piece of the promised land,” she says.

The site

“Building something out of nothing is an awesome story to tell,” Horne says proudly.

She relays these accounts as a descendant, educator, and park ranger at the visitor center in the Nicodemus National Historic Site. Nicodemus is the oldest and sole remaining predominantly African American western town established in the late 19th century.

The settlers of 1877 arrived with meager supplies, tools, and no firearms. Their first winter was grueling, according to Horne. They survived in sod-covered dugouts and nearly starved to death. A group of Pottawatomi Indians traveling through the area after a hunt shared their game and government supplies. But even in these harsh conditions, a school and church were established in a dugout within months.

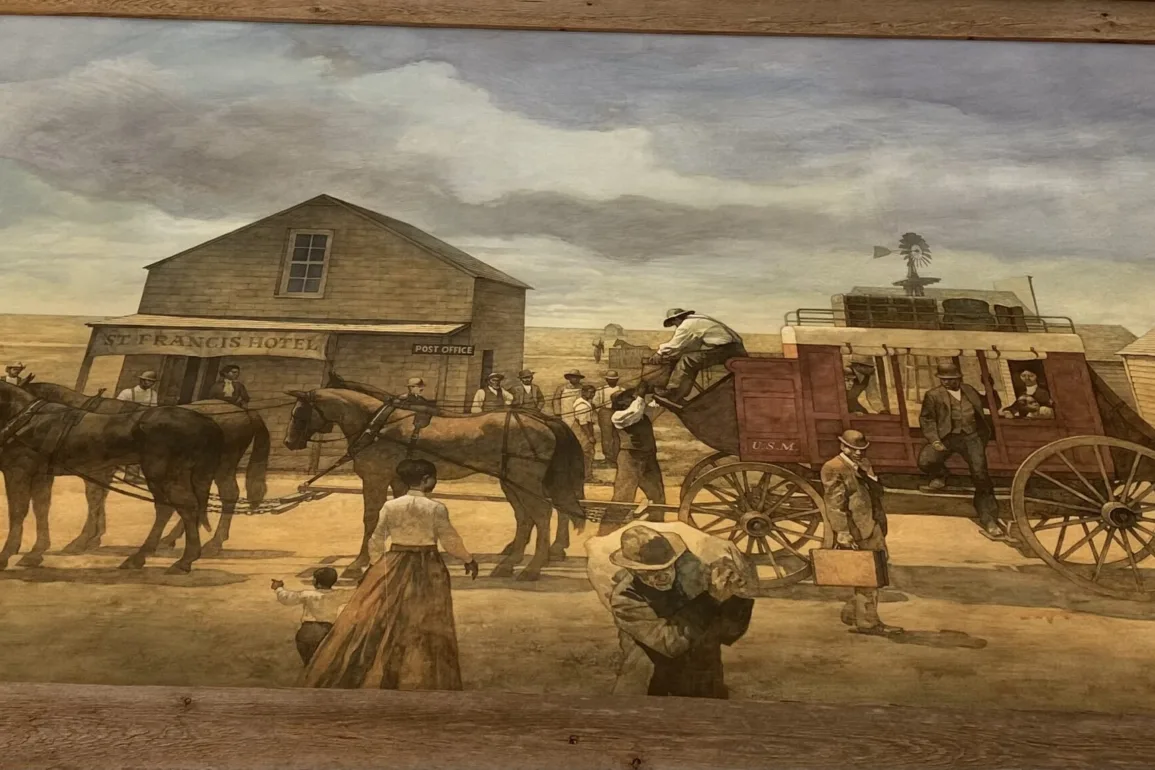

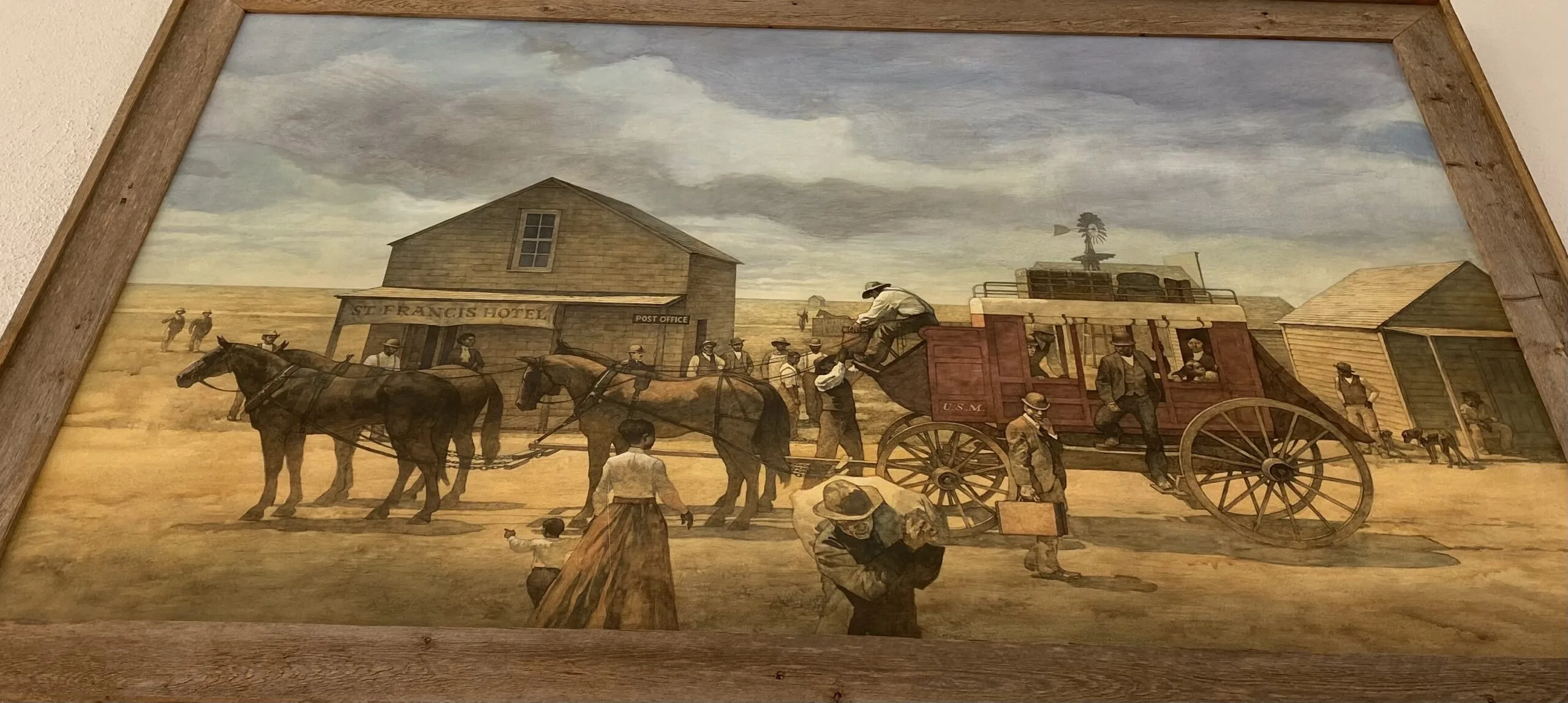

By the mid-1880s, Nicodemus had established a population of 550, with two newspapers, a bank, law offices, churches, mercantile stores and boarding houses. The Fletcher-Switzer House, still standing, housed the post office and hotel.

But growth and prosperity were temporary. By 1885, the promised railroad bypassed Nicodemus. Businesses closed, leaving the town in economic ruin. The Johnsons remained, however, and their descendant, Veryl Switzer, continued to farm their land until the mid-1990s. Switzer is a legend in these parts, earning All-American honors as a running back and defensive back for Kansas State University in the 1950s.

The 2020 census counted 14 people as residents of Nicodemus. Horne grew up in Topeka but enjoys recalling summer vacations in Nicodemus.

“My mother would drop us off at a cousin’s house,” Horne says. “And we’d have cousins from California, Detroit, and Kansas City. So when I had the opportunity to move back to the area and work in Nicodemus, I jumped at the chance. I felt that nostalgia. I gotta get back home.”

The Nicodemus National Historic Site is one stop on the Kansas African American History Trail, eight places that tell important stories of African Americans in Kansas and United States history.

When you visit

“The best time to come is when you can arrange a personal tour and stay overnight,” recommends Angela Bates. “At night, see the stars away from the lights. Take the time to get a feel for the African American experience in the west.”

Bates was born in Nicodemus, but her family moved to California when she was 5. Recognizing her hometown was vanishing, she returned in 1989. She established and operated the Nicodemus Historical Society.

“It’s the only place I’ve ever wanted to live,” she says.

You can visit Nicodemus any time, but you might want to visit during one of the annual events. The annual Emancipation/Homecoming Celebration is always the last weekend in July and is a three-day reunion for descendants and well attended by the public, complete with a parade, music, great food, and conversation.

Pioneer Day, another annual event, is usually the first Saturday in October and always celebrated with a historical theme, including food, performances and presentations. For visitors, these two public events provide an educational experience while also participating with or visiting descendants of those pioneer settlers.

Wayne Hare, a writer and recent visitor, adds: “The feeling I got was one of awe and admiration at the hard work and determination it took to create this community.”

Frank Barthell is a former video producer at the University of Kansas. Through its opinion section, Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate. Find information, including how to submit your own commentary, here.