As we continue to mark the Inlander’s 30th anniversary, every week we’ll look back at a different article from years past. This week, we’re rerunning a piece originally published on Feb. 2, 2000 and written by Ted S. McGregor Jr. Also, watch for our 30 Years of Inlander feature every week in the paper through Oct. 12.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE: In the nearly 25 years since this story was first published, the term “gypsy” has become widely considered an offensive term. Today, we would use “roma” or “romani” to describe Jimmy Marks background. You will see the outdated term throughout this story, however.

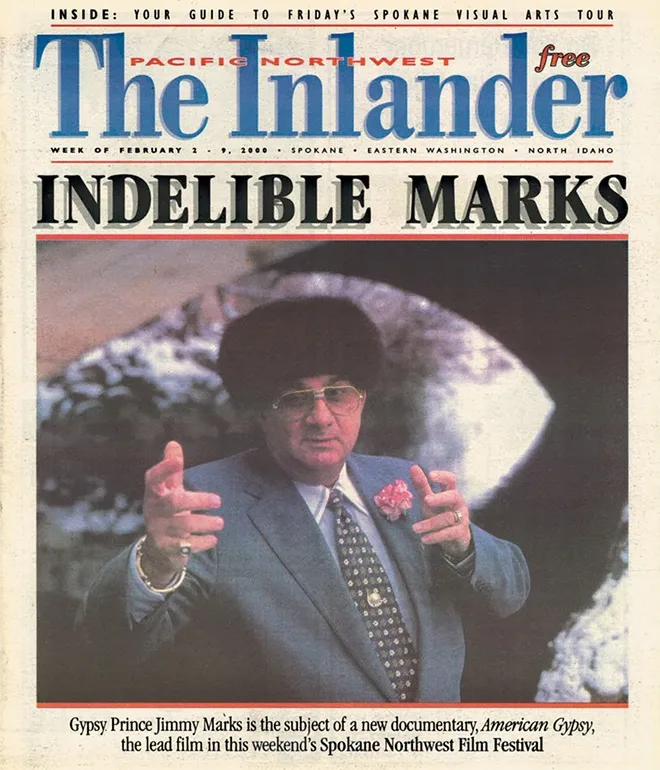

Spokane Gypsy Jimmy Marks has been a lot of things to a lot of people. To his own culture, he has been known as a senator, a king in waiting and, lately, an outcast. To the city and county of Spokane, he has been seen as a criminal and a major pain in the backside for more than a decade. In his own thinking, he has gone from scrappy businessman to a transitional figure in the history of his people; Marks says he is to the Gypsy culture what Rosa Parks was to African-Americans. Now you can add another title to his long list: film star.

When the Spokane Northwest Film Festival opens its second annual run on Friday at The Met, the lead film, American Gypsy: A Stranger in Everybody’s Land, will feature none other than Jimmy Marks. And while the documentary goes well beyond the personal story of Marks, his life and struggle with local authorities provide the narrative thread that holds the film together.

Filmmaker Jasmine Dellal first conceived of doing a film on Gypsy culture in the early ’90s as a graduate student in journalism at the University of California at Berkeley.

“In Berkeley, I became aware of one ethnic group that didn’t seem to be protected by the politically correct police,” says Dellal from New York City. “The same people who would say, ‘Don’t say black, say African-American,’ would turn around and say, ‘Don’t get gypped by the Gypsies.’ ”

Dellal, who will be in Spokane for the screening of her film, has another, more personal connection to Gypsies. As both Jewish and Indian growing up in England, she felt some sympathy for minorities of any kind And Gypsies were found to be the ethnic group held in the lowest regard of all ethnic groups by a survey of The New York Times (even lower than a fake ethnic group they threw into the mix). But what finally cemented her interest was a journalist’s desire to shine a light on a culture that has been cast in shadow for more than a millennium.

“I started paying more attention to Gypsies, investigating it further,” Dellal recalls. “I did a Nexis search for ‘Gypsy’ and only 45 references came up. If you type in ‘Jew,’ they tell you there are too many references to list.”

After she decided to make a documentary on Gypsy culture, she started looking for a person or family to use as the centerpiece of her film. One of the first things she learned about gypsy culture was that the members of Romany culture, as they call it, didn’t want anyone to learn its secrets. She was hung up on repeatedly, and nobody would even return her phone calls. Until Jimmy Marks.

Here was a person who claims to have dedicated his life to helping promote understanding of Gypsy culture. What Dellal found out, however, was that Marks had a huge ax to grind about his ongoing case against the city and county of Spokane for a police raid in his home in 1986. When Dellal first met Marks in 1993, she laid out some ground rules to keep her work from slipping toward propaganda: she wouldn’t promise that there would be anything in the final film about his case; if there was something in it about the case, she couldn’t promise it would be in his favor; and he couldn’t tell her what to put in the film or take out of it. Marks agreed, Dellal started filming in 1994 and five years later, American Gypsy was completed.

So far, the film has been extremely well received, says Dellal. She first screened it last year at a Gypsy caravan in Austin, Texas. She was nervous, since most in attendance were predisposed to not like any intrusion into their culture. She was pleased, however, as it was warmly embraced and led to some lively discussion with those in attendance.

Next, the film was booked into the prestigious Margaret Mead Film Festival in New York City, home to tens of thousands of Gypsies (estimates put the nation’s Gypsy population at around 1 million). The first night, the film sold out. The next night, the film was moved to a bigger theater, which was also packed with a standing room only crowd. It’s a strong response for a first film, and Dellal, who plans to continue making documentaries, reports that PBS is scheduling a nationwide broadcast of the film sometime this year.

As for Marks, he and his family screened it privately the night before the Austin showing. Marks, who simply says he trusted Dellal to tell his story based on a “gut feeling,” only complained that the film “wasn’t long enough.” In the end, the 80-minute film did come to tell quite a lot about the Marks controversy that has dominated local headlines from time to time over the past decade-and-a-half.

But Marks clearly relishes the notoriety that comes with being up on the big screen. He reports with obvious glee that a screening in Romania, homeland of his ancestors, inspired one local Gypsy to tell an interviewer: “I wanna be Jimmy Marks! I wanna sue America, too!”

Gypsy culture collided violently with gaji culture (their name for the rest of American society) on June 18, 1986, in southeast Spokane. That day, a task force made up of Spokane County Sheriff’s deputies and Spokane Police Department officers, served a search warrant on Jimmy Marks’ home and the home of his father, Grover, who lived a few blocks away. Expecting to recover stolen property, the police found a cache of money and jewelry that took hours to gather up and haul away. In all, $160,000 in jewelry (more than 500 items) and an incredible $1.6 million in cash were hauled away from the two homes.

What followed was more than a decade of arguing about what actually happened that day, when it happened and who was responsible for how it happened. The Marks family went through 23 attorneys costing more than $500,000; the city spent more than $1 million in an eventual settlement of the civil suit that came later and countless thousands more defending itself. The county paid $390,000 on that settlement, along with its own attorneys’ fees.

So what did happen that day? Jimmy Marks, who only took $1 as his share of the settlement with the city, puts it quite simply: “They can call it what they want, but it was an armed robbery.”

Although the Spokane City Attorney’s office was starting to put the case back together when the city council decided to settle in 1997, court rulings following the raid seem to side with Marks’ assessment.

Despite advice from the U.S. Attorney’s office on the day of the raid to go ahead and seize the cash, the judge who issued the search warrant ordered the money returned just a week after the raid. Although the Internal Revenue Service decided to hold the cash for possible tax evasion, it wound up giving almost all of it back. Ultimately, a judge ruled that the search began prior to the signing of the warrant. While that ruling was later eroded by appeals, much of the evidence gathered at the raid could not be used to prosecute the Marks. Finally, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, while restoring much of the validity of the search warrant, ruled that people in the homes that day, but not named in the warrant, were illegally searched.

Although the City Attorney’s office seemed to be turning the corner on the case and was even ready to seek a final ruling from the Supreme Court on the issue, the matter was settled out of court. The $1.43 million settlement was a far cry from the $40 million being sought, but it still ranks among the highest awards in the nation’s history for a case of police misconduct (by comparison, Rodney King was awarded $3.8 million for being severely beaten by police officers in Los Angeles). As part of the settlement, the city of Spokane has admitted no wrongdoing.

Clearly, however, mistakes were made on the part of the police and public officials — honest mistakes, you can argue, but mistakes all the same. The raid was hurried up because police believed the Marks, who were under surveillance and being wire-tapped by a police informant, were onto the sting operation. Judge John Schultheis later ruled that the police jumped the gun by beginning the search before the warrant was signed at 3:10 pm. While officials argue the search started at 3:30 pm, they apparently didn’t establish the time well enough for the raid to hold up.

After Schultheis’s ruling, the county prosecutor’s office decided not to appeal all parts of his ruling, only going after those parts that would allow for the continuance of criminal charges against Marks family members. That failure to appeal key elements of the case would haunt the city of Spokane for years after it was sued by the Marks for a violation of their civil rights — a case that was also enabled by Schultheis’s ruling.

Ultimately, the county secured guilty misdemeanor pleas from Jimmy Marks and his mother Lippie (then in her seventies) for dealing in stolen property. As Jimmy Marks puts it, it cost his family $500,000 to defend itself from what boiled down to him buying items worth less than $10.

But in reviewing the details of the case, it appears that Marks may have slipped by; for all his complaints about its injustices, the gaji judicial system appears to have served him pretty well. Had the raid withstood the legal challenges, Rocco Treppiedi, the assistant city attorney who led the effort on the case, says the charges against him would have been pretty tough to beat. Not only did they have wire-tapped conversations of Jimmy Marks discussing homes the police informant should burglarize, Treppiedi also says they had the damaging testimony of a relative of Marks who was privy to conversations on the evening of the raid and throughout its aftermath.

Since much of the evidence never saw the light of day in a courtroom, and since the pending civil suit silenced its defendants, the war of public opinion was often won by Marks, who, despite being illiterate, showed a real knack for media relations. Today, the popular image of Marks as a man wronged has left a bitter taste for police and public officials who have been left to complain about a judicial system they say let down good police work and to criticize local media for not telling the whole story.

The week after the settlement, former Assistant Police Chief Clifford Harding broke his silence and wrote a commentary in The Inlander. Harding wanted to remind people that property from 35 different burglaries was identified from the raid, and he expressed his disgust with the judicial system and his thanks for the city council and staff’s support through the years.

“Contrary to claims made by the Marks and widely reported in the media,” wrote Harding, who was personally named in the civil suit, “the events in June, 1986, involved excellent police work. The lawsuits resulted from the inability of the criminal justice system, and subsequently our civil court system, to exercise common sense and give us our day in court.”

It was a reminder that before the case took on mythic proportions, it was a simple bit of police work. But to much of the local population, it was looking like the city’s legal staff was obsessed.

“It was not an obsession,” says Treppiedi, “it was pure justice. Jimmy Marks perpetrated a hoax on the system.”

“You know what they are?” says Marks of all those he sees as his persecutors. “They’re bullies. And bullies don’t like to lose.”

It’s the same point he was apparently trying to make when he handed out baby pacifiers to city council members just after they held a press conference to discuss the settlement in July, 1997.

Lifted by the prominence of perhaps the city’s biggest legal challenge ever, Marks became something of a media darling. He was profiled by ABC, CBS and NBC, was written up in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal — he and his family even appeared on The Jerry Springer Show. But while his on-screen stock was rising, he was being outcast from his own Gypsy culture. His father Grover (who died three years ago) was a Gypsy king in the culture’s hierarchy, but if that made Jimmy a prince, he is now a prince in exile. He still resides in that no-man’s land, waiting for Gypsy elders to perhaps lift the banishment.

“My father was a Gypsy king,” Marks says, “now I’m a madman. I’m not allowed to go to weddings, funerals. My children and grandchildren will always be haunted by what happened here.”

Marks says he has been outcast from the Gypsy nation for the indignities suffered on the day of the raid. Since police defiled their homes and mixed with their families, it has made them unclean, he says. Others, however, suggest Marks may be outcast for bringing trouble to the Gypsies. Elders are said to have told him not to fight the raid in court. Since Gypsies like to live outside the boundaries of mainstream society, when more scrutiny is put on them, for whatever reason, it makes them uncomfortable.

Either way, Marks says his sons can’t even find suitable wives (all marriages are still arranged in Gypsy culture). Under the circumstances, Marks has chosen to do something few other Gypsies have ever done; he intends to devote his life to improving awareness of the Romani culture.

And as Dellal’s film shows, it’s a culture steeped in a harsh history. Although many (including Gypsies themselves) once believed they were descended from Egypt (thus the name), the truth is they first migrated from India to Europe more than 1,000 years ago, where they quickly spread out. The Marks’ ancestors are among the most hard luck Gypsies you can find; they ended up in Romania, where they were enslaved for more than five centuries. Old prejudices die hard, and Adolf Hitler’s very first concentration camps were built for Gypsies. That more than 1 million Gypsies were slaughtered during the Holocaust has been another Gypsy secret until recently, when a Gypsy was selected to sit on the board of directors of the Holocaust Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Around the turn of the century, Marks’ great grandfather managed to immigrate to the U.S., where he was greeted with similar prejudices in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty. Marks relates a family story of his great grandfather telling his name to the immigration officers at Ellis Island. Angry at him for being a Gypsy and unable to pronounce his name, they thrashed him and said “Put down ‘Marks’ for his name for the marks on his back.”

Of course, it’s hard to know whether the story is true because another hallmark of Gypsy culture is storytelling. In American Gypsy, Dellal seems to suggest that lying (at least to the gaji) is expected. In fact, Lippie Marks’ nugget of Gypsy wisdom — “There is no truth” — could be the epitaph for the entire controversy that has plagued her family.

The Marks came to Spokane from Salt Lake City in the 1950s, and like all good Gypsies, Jimmy Marks quit school after the second grade so he could work; he still has to have a neighbor read his press clippings aloud to him. By 12, he was working full-time, and he eventually worked his way into the family business of buying and selling used cars (keeping up the tradition of horse trading that his own ancestors practiced).

But Jimmy has varied from the usual Gypsy script, even going so far as to let his grandchildren learn how to read at the gaji schools. He bemoans the fact that they don’t speak Rom, but he says the culture has to change to survive. Although he doesn’t articulate it this way, perhaps Marks recognizes that by maintaining such separateness from mainstream culture, they ensure ignorance about their culture. And from ignorance comes prejudice. So his effort to “throw open a window for non-Gypsies” may be nothing more than a desire to see his grandchildren grow up to face less prejudice than he did. Perhaps his feeling of kinship with Rosa Parks is not so far-fetched after all?

In this era of celebrating diversity, Gypsies are perhaps the most challenging ethnic group to embrace, which is how they have wanted it. Their culture is, by many people’s standards, primitive, brutal, chauvanistic and superstitious. How we react to such a culture is something buried deep within, only to be dealt with through exposure, education and, at times, crisis. White America has struggled through this (you only need to look at the South Carolina State House to know that it’s a process that remains incomplete) with other groups that, unlike Gypsies, reside in (or closer to) the mainstream, from African Americans to Native Americans. But how those pesky prejudices affect the majority is hard to pin down. Were the Marks targeted by law enforcement in 1986 ahead of other suspected fencing operations because of such prejudices? Public officials say no way; racial profiling is not a part of local law enforcement, they insist. But to the Marks, they’ve known the answer since they were born in a foreign land, like every Gypsy for 1,000 years.

The impressive fact that Gypsy culture has survived with its language and traditions intact for a millennium without a homeland, especially when it has been besieged at every turn by slavery, genocide and simple prejudice, was the part of the story that captivated Dellal. Despite the quick impression of Gypsy culture as brutal and superstitious, she thought there had to be something there that has allowed it to survive — a resiliency worth exploring.

“This is a culture that bends so it won’t break,” says Dellal. “It absorbs enough of the surrounding culture so that it can survive. I hope people will come out to learn about the culture. It’s an ancient culture, and it’s a family-based culture. In fact, Gypsies have a family ethic that even Dan Quayle would be proud of.”

Dellal’s film shows that in five years, she came to respect the culture, but she manages to keep a soft, anthropologist’s touch; she resists the temptation to apply mainstream sensibilities to her subjects and instead just shows the culture as is. There are times, however, when her camera betrays a personal bias. In one scene, where Grover and Jimmy are going on and on about their case, she allows her camera to linger on Lippie, who is struggling to walk across the room behind the two men. It suggests a sympathy for Gypsy women, who have not been allowed to experience women’s liberation yet.

And Dellal manages to show Jimmy Marks’ human side by replaying messages he has left on her answering machine. These audio tapes are both touching and funny, and they allow a glimpse behind Marks’ tough facade.

“I didn’t do a film that says the Marks are crooks or that the Marks are angels,” says Dellal. “Still, it’s difficult not to empathize with a family that has gone through so much drama over the past decade.”

And that’s just what the best documentary filmmakers want to do; they want to provoke empathy in their audience, and understanding of something that hasn’t been understood. On that count, Dellal’s precocious film succeeds.

“Prejudice arises from ignorance,” says Dellal. “That’s true of all prejudice, and, in the case of the Gypsies, it’s hard to correct that ignorance since there’s so little known about them. Hopefully [American Gypsy] will help people question the stereotypes.”

As for Jimmy Marks, he’s embroiled in another struggle, this time over a Labor Day incident at Holy Cross Cemetery, where his grandparents are buried. Gypsies commune with the dead (including blowing cigarette smoke into the grave and pouring beer into the earth), and when some of his relatives were doing this, a Spokane County Sheriff’s Deputy confronted them for disturbing the peace. A melee ensued which resulted in injuries to the deputy and to two of the Marks, who wound up in jail.

With typical Marksist rhetoric, he wonders why the police don’t crack down on drinking wine with communion at Roman Catholic services. He says this kind of treatment has led the local Gypsy community to shrink, from 250 prior to the raid in 1986 to less than 50 today. Marks says the FBI is investigating the police’s role in the Holy Cross incident, and that the county has hired an attorney to handle the case. County officials couldn’t be reached for comment.

So perhaps Marks will be remembered by future generations of Gypsies as the first one to fight, the first to stand up to the gaji, the first one to say, “I’m not sittin’ on da back of da bus no more,” as he barks it. Whether he will become a chapter in the history of the Gypsies or just a footnote remains to be seen, but he is certainly carrying on the culture’s central tradition: survival.

“Gypsy culture will survive,” he says softly, after a moment of reflection. “We’re survivors of the Holocaust, the plague, the wars,” his voice rising. “We’re survivors of the world.

“And,” he concludes, his voice settling down again as an impish grin spreads across his face, “we’re survivors of Spokane.” ♦