THE WESTERN IS the quintessential American film: the genre captures the ideals of American individualism while also showing the horrors that it produced. From the early origins of film through most of the 20th century, the Western film genre provided a model of cinematic storytelling that brought together themes of failure, triumph, struggle, and redemption set in the “lawless” American West. For many, the Western embodied the American Dream: the ability to start out with nothing in a new place and build success. The Western film has been so popular that it has gone on to inspire subgenres around the globe, from Italian “spaghetti Westerns,” to Indian “dacoit Westerns” and even Soviet “Osterns.” If jazz is the United States’ musical gift to the world, then the Western is its chief cinematic contribution.

Yet the idea that a Western movie can carry a civil rights message seems paradoxical. If anything, the Western represents the antithesis of civil rights and racial equality. For most of its existence, the Western genre has been tied to the history of the extermination of Indigenous peoples and wholesale violence in the service of promoting a positive narrative of white American expansionism. Until the release of Buck and the Preacher in 1972, which boasted a majority African American cast led by Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte, very few Westerns ever sincerely examined the issue of race critically, instead opting to incorporate the theme of racism in a way that, at best, offered progressive, against-the-grain readings.

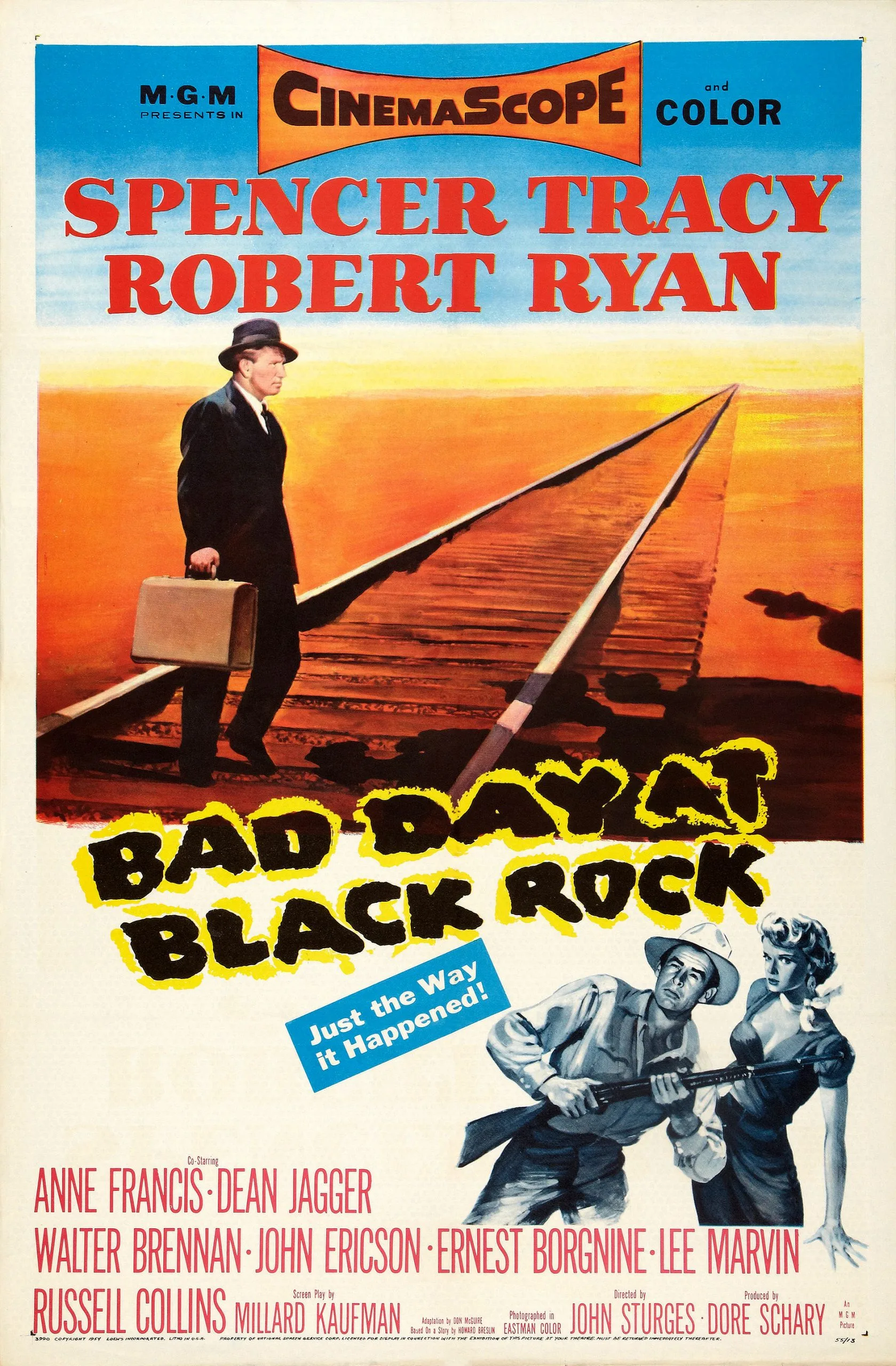

Yet, hidden amid the long filmography of Westerns, a few “unknown” films examine prejudice and civil rights, such as the 1943 film The Ox-Bow Incident, which dramatizes the horror of lynching. An even more powerful example is the 1955 film Bad Day at Black Rock. One of the first Westerns by director John Sturges—who, five years later, achieved international renown for directing The Magnificent Seven—Bad Day at Black Rock boasts a star-studded cast. Spencer Tracy appears in the lead role opposite Robert Ryan, with supporting performances from Ernest Borgnine, Walter Brennan, John Ericson, Anne Francis, Dean Jagger, and Lee Marvin. The film won less attention upon its release than its contemporary Westerns, High Noon (1952), Shane (1953), or The Searchers (1956); today, it is relatively obscure to the public. In recent years, industry veterans and film critics have lauded it as a cinematic triumph and an important chapter in Sturges’s career. Paul Thomas Anderson told the Los Angeles Times that you can learn more from Sturges’s discussion of the production of Bad Day at Black Rock than from “20 years of film school.” Along with its cinematic qualities, the film is remarkable for its commentary on racial violence in the American West. Released amid national debates on civil rights and desegregation, it offers a critical discussion of racism through the story of the lynching of a Japanese American during World War II.

Set in the isolated town of Black Rock in 1945, the film opens with a Santa Fe Streamliner racing across the Owens Valley, accompanied by André Previn’s thunderous score. The train makes a sudden stop at Black Rock, thereby surprising the inhabitants, as the town has not received any visitors since before the war. Enter John J. Macreedy (Tracy), a jaded veteran who lost his arm in combat. He decides to visit Black Rock in search of a man named Komoko, a Japanese American farmer whose deceased son, Joe, saved his life while fighting in Italy, and give the man his son’s medal.

Macreedy makes several attempts to inquire about Komoko and his farm at Adobe Flat, but the townsfolk become increasingly anxious and hostile to his every question. The town’s assumed leader, Reno Smith (Ryan), attempts to nudge Macreedy into giving up his search quietly. Persistent, Macreedy rents a jeep from Liz (Francis), the town’s mechanic, and drives to Adobe Flats. There, he finds the remnants of a burned farmhouse and a well still containing water—a rarity in the desert landscape. Near the house is a small patch of flowers, which Macreedy immediately recognizes as the site of a grave.

En route to Black Rock, Macreedy finds himself ambushed by Smith’s thug Coley (Borgnine) and driven off the road in the Alabama Hills. He realizes now that Smith and his compatriots want him dead—buried away, like the memory of Komoko. He tries to escape, only to find that Smith’s henchmen have cut off any access to transportation. His attempts to call for outside help are silenced by the telegraph operator, who cooperates with Smith by handing him Macreedy’s message. When he attempts to find solace at a lunch counter, Smith’s men corner him into a fight. In the most daring scene of the movie, the one-armed Macreedy judo-chops a brutish Coley, stunning him and the others with his grit.

Yet Macreedy’s show of force is not enough. Realizing that Smith’s men will wait until dusk to kill him, Macreedy finds refuge in the hotel with the town’s sympathetic coroner Doc Velie (Brennan) and the hotel clerk, Pete (Ericson). The two confess the story of Komoko’s demise: Komoko purchased Adobe Flat from Smith, who believed the Japanese American farmer would fail because of the lack of water. Komoko persisted and dug a well deep enough to produce. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Smith was rebuffed by Marine recruiters. In a drunken rage, Smith and the others set Komoko’s house on fire, and, as Komoko emerged from the burning house, Smith shot him to death. Since then, Smith has ruled Black Rock, whose denizens have shared the guilt of collaborating in the murder.

Doc and Pete, to atone for Komoko’s murder, agree to help Macreedy escape. They ambush Smith’s henchman Hector (Lee Marvin), giving Macreedy time to flee with Liz in her jeep. As Macreedy is driven into the desert, he suddenly realizes that Liz is handing him over to Smith at the site of Komoko’s farm. Smith appears and murders Liz in cold blood to avoid witnesses. As Smith takes several shots at him, Macreedy uses his army training to fashion a Molotov cocktail with gas from the jeep. He launches the grenade at Smith, setting him ablaze as the villain had once done to Komoko.

The next day, Macreedy returns to Black Rock with the bodies of Liz and Smith, and police arrive to arrest Smith’s henchmen. As Macreedy prepares to leave Black Rock, Doc asks him for Komoko’s medal, hoping that it will help the town heal. Macreedy leaves the medal with them and boards the Streamliner bound for Los Angeles.

When it premiered at Loew’s 72nd Street Theatre in New York City on December 8, 1954—over a decade following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the US entry into the Pacific War—Bad Day at Black Rock was a hit. Observers at the premiere commented that “the suspense was so terrific you could have heard a pin drop.” Following the film’s screening at the Rivoli, both Bosley Crowther of The New York Times and William Zinsser of the New York Herald Tribune likened Bad Day at Black Rock’s build-up of suspense to that of High Noon and lauded the intense drama wrought by Sturges. Bad Day at Black Rock fared well on the awards circuit; at the 1955 Cannes Film Festival, Tracy earned the Best Actor award, and Sturges was nominated for the Palme d’Or. Although the film did not receive any awards at the 28th Oscars, Tracy, Sturges, and screenwriter Millard Kaufman all received nominations for their contributions. (Ironically, Tracy lost the Best Actor award to his co-star Ernest Borgnine, who won for his role in the film Marty.)

The film even impacted international relations; the State Department asked producer Isadore “Dore” Schary, then president of MGM, not to release the film in East Asia over concerns that depicting the lynching of an Asian American would strain US relations with East Asian countries like Japan. Schary shot back that the lynching does not appear on-screen, and that setting the film in the past would further underscore how the murder transformed the town.

Aside from its suspenseful murder plot and the high-quality acting of Tracy and Ryan, Bad Day at Black Rock stands out as one of the few Westerns of the 1950s to present racism as its central subject matter. Although several film critics have interpreted the persecution of Macreedy in Bad Day at Black Rock as an allegory for McCarthyism, the film’s discussion of anti-Asian racism during the war is equally noteworthy. Though no Asian characters appear, the incarceration of Japanese Americans is mentioned throughout; at one point, Smith attributes Komoko’s disappearance to the fact that he was “shipped […] off to a relocation center.” Although it only mentions incarceration in passing, the film’s power lies in its attempt to dramatize the racism that both motivated forced removal and the postwar movement to keep Japanese Americans out of California.

Bad Day at Black Rock fits into Schary’s long history of producing message films about tolerance—first at RKO Pictures, where he greenlighted the production of Crossfire (1947), and then at MGM—along with his connection to the Japanese American community and his fascination with the incarceration story. Although Sturges gave the film life with his talents as a director and Kaufman transformed Howard Breslin’s short story into a celebrated, suspenseful drama, Schary was in many ways the engine behind its creation and the public face of the project. “Dore Schary […] strove for drama in the pictorial scene,” Bosley Crowther asserted in his New York Times coverage. And as David Thomson would later write of the film, “[N]o one has ever questioned that [the film] was [Schary’s] idea,” adding that “[f]or Schary and his like it’s a comfortable feel-good film, as opposed to a genuine exploration of social and political trouble.”

Schary’s numerous appearances in the Japanese American press (i.e., the Los Angeles–based Rafu Shimpo and the Japanese American Citizens League’s publication Pacific Citizen), along with several mentions in interviews and in his 1979 memoir Heyday, indicate that the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans left a deep impact on him. His feelings on the subject led him to produce two major pictures despite objections from MGM executives: Go for Broke! (1951), the saga of the all–Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team; and Bad Day at Black Rock, a study of the anti-Japanese sentiment that dominated West Coast cities during the war.

Schary’s fascination with the wartime experiences of Japanese Americans long predated his work on Bad Day at Black Rock. According to journalist Larry Tajiri, Schary began developing several ideas for films about Japanese Americans in 1947, during his time with RKO Pictures. One film that was eventually canned for being too similar to Madame Butterfly was an interracial love story involving a nisei, or second-generation Japanese American. Another story, Honored Glory, would include several tales about American soldiers buried at Arlington National Cemetery, with one featuring a Japanese American who enlists from camp and dies in Europe. This story, developed with writer Robert Pirosh, was delayed due to Schary’s departure from RKO to become vice president of production at MGM. Pirosh followed Schary to MGM, and the two developed Honored Glory into the 1949 film Battleground.

In May 1951, following up on the success of Battleground, Schary and Pirosh fulfilled their dream of collaborating on a film about Japanese Americans by making Go for Broke!, with Schary as producer and Pirosh as director. One of the first major films about Japanese Americans, Go for Broke! follows a prejudiced army officer from Texas (Van Johnson) who begrudgingly accepts a commission with the Japanese American unit. Over the course of the film, Johnson’s character learns to accept his Japanese American comrades and even to appreciate their heroism, despite pressure from fellow Texans who remain racist.

While Go for Broke! focuses more on the transformation of Johnson’s character and less on the actual experiences of the nisei soldiers, the film was a major public relations success for the Japanese American community. Alongside Samuel Fuller’s The Steel Helmet (1951) and King Vidor’s Japanese War Bride (1952), Go for Broke! was among the first of a handful of postwar Hollywood movies to mention the incarceration. In addition to the film’s casting of several former members of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, members of the Japanese American Citizens League, notably its leader Mike Masaoka, served as technical consultants and promoted the film in the Pacific Citizen. Go for Broke! also marked the beginning of a friendly relationship between Schary and the JACL.

During the production of Go for Broke!, Schary made significant efforts to reach out to the Japanese American community. In preparation for the premiere, he wrote an exclusive article for The Rafu Shimpo declaring to readers that the movie was “a special tribute to the Nisei,” and that the story of Japanese Americans “held a very special interest to [him].” As a gesture of gratitude toward the community, Schary donated $3,500 to the JACL for their cooperation in making the film. Masaoka and the JACL were so proud of Schary’s production that they presented him with a leadership award and invited him to be the keynote speaker at their 13th Biennial Convention in Los Angeles. Pacific Citizen editor Larry Tajiri maintained a continued interest in Schary’s career long after the release of Go for Broke!, with Schary appearing frequently in his columns until Tajiri’s death in 1965. Although Pirosh and Schary ceased collaborating after 1952, Pirosh also remained a memorable figure for Japanese Americans as a result of his work on Go for Broke!

If Go for Broke! was Schary’s introduction to the story of Japanese Americans, Bad Day at Black Rock was its logical continuation. To write the story, Schary brought veteran screenwriter Millard Kaufman onto the project. Kaufman later explained to the San Francisco Examiner that he was inspired to take on Bad Day at Black Rock at the suggestion of his friend Arthur Laurents, who had written the 1945 play Home of the Brave about prejudice in the Marine Corps. (In Laurents’s original play, the victim is Jewish; in the 1949 film adaptation by screenwriter Carl Foreman, he is Black).

Like Foreman, Kaufman adapted his script from a previous source, Breslin’s 1947 short story “Bad Time at Honda.” Kaufman made significant changes to Breslin’s plot: in the original, Komoko—spelled “Kamotka”—was not shot but died of a heart attack in response to a gun being shot in the air by a sympathetic citizen to warn him of an incoming lynch party. The town also does not feel remorse for their actions until Macreedy informs them that Kamotka’s son died while in the service, making Kamotka the father of a war hero. Despite these major modifications, Breslin personally congratulated Schary for a successful adaptation of his original story after the film received critical acclaim.

To bring authenticity to the film, Schary, Kaufman, and the production staff conducted extensive research on anti-Japanese violence in California. Most of the reports of violence Schary’s staff pulled focused on Japanese Americans attempting to return to California in 1945, after the Supreme Court ruled that the government must release concededly loyal citizens. Ironically, these accounts had originally been compiled by the War Relocation Authority—the government agency that ran the 10 concentration camps and also oversaw the postwar resettlement program of the community. WRA officials recorded dozens of cases of shootings, arson, and death threats against Japanese Americans returning to California in 1945, often with local law enforcement doing little to address the violence. One notable incident involved local whites in Placer County who dynamited the farm of a returning Japanese American farmer, Sumio Doi. The four perpetrators were arrested, but the lawyer won their defense by arguing, “Let’s keep this a white man’s country.” In November 1945, two murders of Japanese Americans were reported in the press: George Yoshikawa, a World War II veteran, was beaten to death in San Jose and left in a vacant lot; the other, Natsuji Kurisu, an elderly man, was shot to death near Ontario, Oregon.

While developing the story, the production team decided to put Komoko’s murder in the distant past. Instead of presenting the murder and Macreedy’s visit in connection with the wave of violence that greeted returning Japanese Americans at the end of the war, they set the crime amid the racial hysteria sparked by the bombing of Pearl Harbor. To be sure, several murders did occur against Japanese Americans in December 1941. On December 23, 1941, a Japanese American man was found stabbed to death in the streets of Los Angeles. Four days later, on December 27, another Japanese American man was shot to death by a Filipino American assailant in Stockton. The Stockton Police Department ordered all Japanese Americans in the city to stay off the streets at night. The San Francisco Examiner played up the story by running the provocative headline “Stockton Jap Killed by Filipino; Riots Feared; Area Under Guard.”

By presenting the film’s murder in the not-so-distant past, Schary and Kaufman show how the lingering secret allows guilt to fester over time, which allows Reno Smith to weaponize the guilt of the inhabitants of Black Rock. While having the murder occur off-screen allowed the filmmakers to avoid censorship, it also served as a case study of how racial violence transforms bystanders into willing participants.

The production team also strove to make the setting as authentic as possible. The film was shot among the Alabama Hills near Lone Pine, just miles away from the original site of the Manzanar concentration camp, closed a decade before. Even the railroad tracks used by the Streamliner in the opening and closing scenes are likely the same ones that carried Japanese Americans to Manzanar in 1942.

The film also drew on scholarly sources, in particular Bradford Smith’s 1948 study Americans from Japan, a text designed to educate the American public about Japanese Americans and their loyalty to the United States. An expert on Japan in the prewar years, Smith wrote extensively on Japanese culture and the rise of militarism. As historian Greg Robinson notes in a biographical article, Smith joined the Office of War Information after Pearl Harbor, where he worked at the Japan desk and collaborated with several Japanese American writers. Once the war was over, he set out to write a book on the loyalty of Japanese Americans that would dispel several popular myths and included several examples of Japanese American soldiers facing harassment. Smith’s book, Carey McWilliams’s study Prejudice: Japanese-Americans, Symbol of Racial Intolerance (1945), and various academic texts, including Alexander Leighton’s The Governing of Men: General Principles and Recommendations Based on Experience at a Japanese Relocation Camp (1945), Dorothy Swaine Thomas and Richard Nishimoto’s The Spoilage: Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement During World War II (1946), and Morton Grodzins’s Americans Betrayed: Politics and the Japanese Evacuation (1949), were prominent among a brief wave of postwar studies that explored Executive Order 9066 and the results of forced removal. Beyond these postwar publications, Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660 and Toru Matsumoto’s A Brother Is a Stranger, both of which appeared in 1946, as well as Monica Sone’s Nisei Daughter (1953), provided the testimony of Japanese American voices.

While mainstream, predominantly white audiences praised the artistry of Bad Day at Black Rock, Japanese Americans did not share in this same excitement. As I wrote for the International Examiner, no Japanese American newspapers covered the release of the film, despite Schary announcing the film’s relevancy to the community in his speech before the JACL’s Biennial National Convention in September 1954. When Larry Tajiri interviewed Dore Schary for the Pacific Citizen in 1955, he made no mention of Bad Day at Black Rock among Schary’s various accomplishments. The reality, though, is that the lack of Japanese American actors may have limited its appeal to Japanese American viewers. With the exception of the African American porter who assists Tracy off the train, all of the characters are white.

Even to this day, Hollywood has produced very few films that center on the wartime experiences of Japanese Americans, the most prominent being John Korty’s 1976 TV film Farewell to Manzanar, adapted from Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston’s book. Those films that have attempted to depict the racist forces behind the incarceration, like Snow Falling on Cedars (1999) and Come See the Paradise (1990), have relied on white savior plots. Vincent Schleitwiler bemoaned the cringeworthiness of Alan Parker’s Come See the Paradise as being “pretty much sentimental mush, but it was well-done professional mush.” Even more recent productions, such as AMC’s The Terror: Infamy (2019), with its added supernatural elements, follow the same basic narrative about the camps.

For some, Bad Day at Black Rock serves as an excellent example of how Hollywood failed Asian American viewers. Director Rea Tajiri interpolated scenes from the film into her 1991 documentary History and Memory: For Akiko and Takashige. Her intercutting emphasizes aesthetic and political erasure—both of Japanese Americans from US history and her parents’ fading memories of the camp. Bad Day at Black Rock has been repeatedly cited by Asian American scholars as evidence of Hollywood’s marginalization of Asian American actors, centering white performers even in cases where anti-Asian hate is the subject matter.

Still, as Tajiri has acknowledged, Bad Day at Black Rock provides a useful framework for understanding how Japanese American history has been erased. Perhaps the most positive appraisal of Bad Day at Black Rock’s legacy in this regard is historian John Streamas’s 2003 article looking at the film together with Tajiri’s History and Memory. Like Tajiri, Streamas argues that Bad Day at Black Rock provides the best starting point for discussing the violence of erasure that afflicted the Japanese American community during and after the war. The hotel clerk Pete’s line—“We were all drunk … patriotic drunk”—illustrates that Komoko’s murder was not an act of racism infused with, even justified by, nationalistic fervor. As Streamas rightly points out, most Americans accepted the “patriotic” racism that Smith espoused less than a decade before Bad Day at Black Rock’s release. Even though the killings of Komoko and his son appear off-screen, they nonetheless eat away at the conscience of the town and, as Streamas concludes, lead its citizens toward their own self-immolation.

As Smith burns to death near the site of Komoko’s farm, a sort of atonement occurs that ends the cycle of guilt controlling Black Rock. While the story focuses on the murder of a Japanese American in 1941, Black Rock arguably serves as a stand-in for any town that participated in racial violence across the United States—a fitting message amid the rise of violence during the Civil Rights Movement. Schary later declared in an interview in 1980 that Bad Day at Black Rock was one of his proudest accomplishments as a film producer.

Even among Asian American writers, Bad Day at Black Rock carries a certain amount of cultural capital related to the camp experience. In a more humorous homage to the film, noted playwright Frank Chin penned a blog post in 2011 reimagining Bad Day at Black Rock as a confrontation between Japanese American resisters and conformists. Chin replaces Spencer Tracy’s Macreedy with activist William Hohri, who led a class-action lawsuit against the government over the community’s incarceration. Hohri challenges Mike Masaoka, the JACL leader who stands in for Reno Smith, and the JACL, who have kept “Black Block,” or Japanese America, from resisting the government. All of Masaoka’s men work as informants for the FBI and army intelligence, actively cooperating with the government to get Japanese Americans to conform with the incarceration. Hohri then “enlightens” the prisoners of Black Block—a reference to the Black barracks of the camp—of their capability to resist the JACL’s orders to collaborate. Even though Chin’s rewrite of Bad Day at Black Rock satirizes the Japanese American Citizens League and the divisions over the meaning of the camps, the homage to Schary’s film points to its lasting legacy.

Fourteen years after Bad Day at Black Rock premiered, a new set of “strangers” arrived in the Owens Valley from Los Angeles in search of the dead. On December 27, 1969, several Japanese Americans, some former camp survivors, gathered at the former site of the Manzanar concentration camp. The event, which became known as the Manzanar Pilgrimage, set off a chain of events that led the Japanese American community to commemorate their incarceration and attempt to remember what happened to them.

Among the group, activist Jim Matsuoka gave a speech that set the tone for the pilgrimage:

A lot of people ask what was Manzanar. We can talk about Manzanar as a matter of statistics; 36 blocks, one mess hall, one laundry barrack, two latrines, one basketball court. To some, Manzanar was just an interlude in their lives. […]

The only people that ever came out of that camp were people without souls, the “quiet Americans”—the people who did not dare to say anything or speak up; the people who were afraid to rock the boat.

When people ask me, “How many people are buried in this cemetery?” I say a whole generation is buried here. The Nisei Americans lie buried in the sands of Manzanar.

Matsuoka’s line “buried in the sands,” speaking literally of those who died while imprisoned at Manzanar, points to the symbolic erasure of Japanese American identity as a result of the camp experience. While there was never a Spencer Tracy figure to save the community, the story of Bad Day at Black Rock recalls a story that was prevalent throughout California in the 1940s, one long forgotten. Instead of one Komoko, hundreds remain “buried in the sands” of the West.

¤