When Black entrepreneurs were struggling against the perils of a global pandemic,

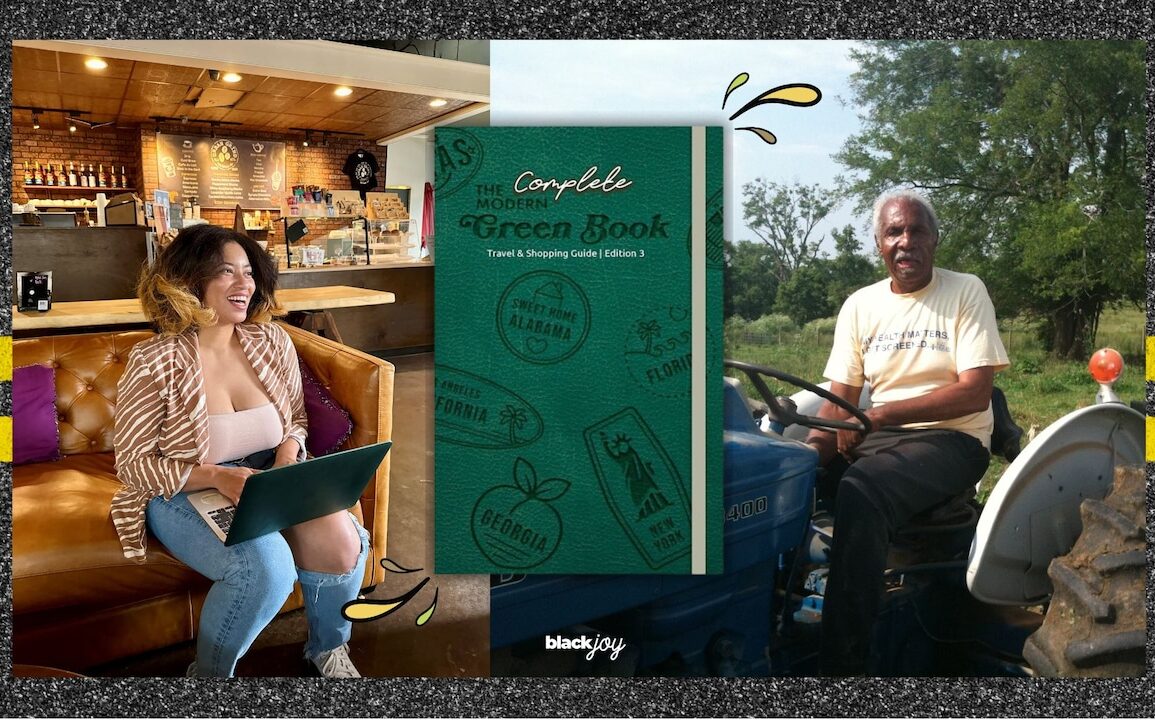

Theo Edwards-Butler responded to their calls for help by pulling from the pages of history and her own family legacy.

In 2020, the contagious nature of COVID-19 forced people to quarantine in their homes. According to the U.S. Small Business Administration, entrepreneurs of color were disproportionately affected by the lockdowns. Black businesses owners witnessed a 11 percent drop in earnings, while white-owned businesses experienced a 2 percent decrease. It was an economic gut-punch that widened the wealth gap for Black entrepreneurs, who already receive three times less capital than white entrepreneurs to start their ventures.

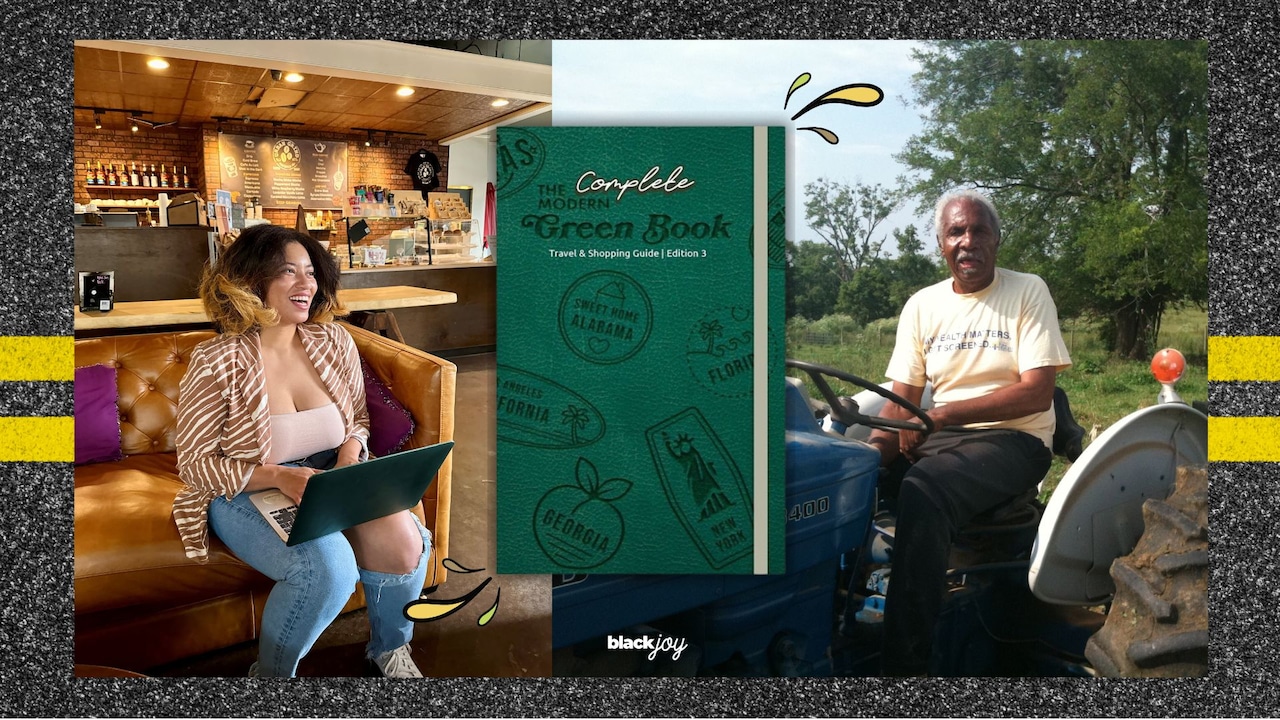

In Birmingham, Ala., Edwards-Butler helped Black professionals survive beyond the statistics by creating a virtual business database called the Modern Green Book. The project borrows its name from the “Negro Motorist Green Book,” a vital resource that helped Black travelers find safe havens to eat, sleep, get gas and more during their road trips across segregated America. The guidebook was published during the mid-20th century by postal worker and World War I veteran Victor Hugo Green. Although different in their objectives, — Green’s work focused on pushing back against racial discrimination while traveling — Edwards-Butler’s support for Black-owned businesses matches the energy of a time when many Americans were challenging systemic racism on multiple fronts following the murder of George Floyd and other Black people at the hands of law enforcement.

“People were looking for a way to continue the protest further than just marching,” Edwards-Butler said. “The Modern Green Book was a way to ensure that our voices would be heard, our dollars would be seen and how impactful the Black dollar and Black-owned businesses are to communities.”

About five years since starting her passion project, more than 2,350 businesses nationwide have increased their visibility and received marketing assistance from the Modern Green Book’s growing platform. In 2021, she organized the inaugural Culture and Commerce Festival, where attendants perused the tents of more than 30 Southern Black-owned businesses and enjoyed delicious foods, a car show and a hip-hop concert. This year’s festival will take place at the end of August, which is Black Business Month. In 2023, she officially launched started the MGB Agency to help entrepreneurs advertise better in a digital landscape.

It was Edwards-Butler’s grandfather, Adee C. Butler, who taught her the power of the Black dollar. Butler was the son of sharecroppers and church leaders. His upbringing in Memphis educated him about the economics behind operating farmland and a place of faith.

“You have to operate a church like how you would operate a business to keep the lights on and to keep the congregation there,” Edwards-Butler said. “So I think he saw his parents go from sharecropping to being community leaders with his church, and then when he got older, he became Mr. Entrepreneur.”

Butler wasn’t a 9-to-5 man. The only boss he had was himself. He owned his own farm near Louisville, Ky., where Edwards-Butler was raised. He owned a gas station, mechanic shop, apartment building and operated a hotel with his sister. Edwards-Butler’s first job was helping her grandmother pluck eggs from the chicken coop on Saturday night to sell to the church congregation on Sunday morning.

“He was a very influential man to the Louisville business community,” Edwards-Butler said.

Butler knew the dangers of conducting businesses while Black under Jim Crow. During family road trips, Butler-Edwards remembers how nervous her grandfather was during pit stops in rural, white towns. He would suggest that they keep going to the next stop, where they would be safer as a Black family. It took Edwards-Butler a little while to sense the risks herself.

“He was very big on ‘Keep your gas tanks full because you never know when your next stop will be’ or ‘I don’t know if we can stop in this town,’” Edwards-Butler said. “There were a few times where we would stop at a gas station, and you would definitely get the vibe [that] they’re serving us because it’s the societal standard to be welcoming to everybody – But they did not want to be welcoming to everybody.”

But that fear didn’t stop Butler from growing generational wealth for his family. He wasn’t the type to stash cash in a mattress. He put his money into assets that would increase in value over time, like property and his coin collection. Before his death, Butler passed down his financial savviness to his son, who later taught those tips to Edwards-Butler.

“He set up our family to be in the position that my parents and even myself are in today,” Edwards-Butler said.

Now Edwards-Butler is using her talents and ancestral wisdom to help Black-owned businesses today, and there’s no better time to do so. The same corporations that beefed up their diversity programs in 2020, are now dismantling those initiatives due to the political attack on diversity, equity and inclusion. Consumers have organized multiple boycotts against Target, Amazon, Walmart and other corporations for going back on their initiatives to support Black entrepreneurs.

Edwards-Butler talked to Black Joy founder Starr Dunigan about the importance of honoring Green’s Legacy and how boycotters can boost their impact even when they live in an area where big-box retailers are all that’s available for their shopping needs.

How were you introduced to the original Green Book and how did that knowledge influence you?

I actually learned about it in high school. There was not a whole section on it or anything like that in our textbooks. It was something that our history teacher told us. He was like, ‘And also during this period of time, there was a book that Black motorists would use to drive around during the Jim Crow era. It was always in the back of my mind, but it was never anything that ever came up in conversation. It’s really not talked about. It’s more likely that people don’t know about it than do know about it.

Then when I was getting this [project] going, I was like, ‘Oh, this is like a virtual Green Book – a modern Green Book.’ So that’s how we got the name for it.

The more research I did into who Victor Hugo Green was as a person and how he wanted this book to become a place of Black excellence, I think that’s what drove me to the creation of the Modern Green Book. I think because I knew what the Green Book originally was and what it stood for, I think that’s what drove me to using that name, that history and that Legacy to build upon.

Since you did a lot of research into Victor Hugo Green, what would it look like to incorporate his vision and passion for Black-owned businesses today?

By going to support these businesses and to make sure they are sustainable and thriving. I think that’s really what it was all about. He wrote a quote in – I can’t remember which book it was – but he said, ‘At some point in time, this book will not be necessary.’ It’s him wanting to have this level of success for Black-owned businesses and for Black people in general to where we can claim our stake in this country and be able to fully embrace who we are as people and our contributions to the country. A good bit of that is the businesses that we’ve created. I think if we all were to continue to pour into these businesses and these entrepreneurs, and continue to build Black businesses going forward, I think that would really honor his vision and his legacy, too.

So you started this project in 2020, which is five years ago. Congrats on that milestone. Can you talk about how the attitudes towards Black-owned business have changed in 2020 versus now?

I definitely think it’s been a bit of a roller coaster with how everybody feels about it. It kind of ebbs and flows. When 2020 first hit we saw maybe a full year and a half of people really, really, really being ten toes down in supporting Black-owned. Then 2023 started and you saw a dip because it was not necessarily the popular thing to do or, you know, people were just doing it so naturally, at that point it wasn’t advertised as much.

But I do think in 2024, we saw a rise of the number of Black-owned businesses. Then the amount of support those businesses received helped them have that longevity because a lot of them are still open today.

I think honestly – and it hurts me to say this – I do think sometimes it takes a big social or political thing to happen for people to really come together to support Black-owned businesses. Like in 2024 when it was election season and we saw [former Vice President] Kamala Harris take on that role, and then we saw Trump get back into [the presidency], everybody’s, ‘OK. Now it’s time.’ I think right now we’re in the upswing of supporting Black-owned. People are actively looking at our website, and they’re not just our normal regulars. We’re getting a lot of new people coming into the community who are looking to support Black-owned businesses intentionally.

As someone who has a deep passion for Black entrepreneurs, how can we make that support more sustainable?

I talk about this all the time because I’m very big on we have to match the energy that our majority-owned counterparts bring to the table. So when I say majority-owned, I mean white-owned, white women-owned, even Asian American-owned. Their communities really, really stick to supporting their businesses. Like, I’ve never walked into a Latin American-owned business and not seen other Latin Americans in there supporting. Right? I think, one, we as a people need to understand that in order for us to get the support we want is that we have to be the people in there giving the support first.

Then two, we’ve got to find a money source to be able to elevate all of our businesses up to the same standard. I think a lot of times when we look at our majority-owned counterparts, they have a lot more marketing dollars, a lot more dollars that they can use on building out brick-and-mortar spaces, a lot more dollars they can use on public relations. So we have to find a money source – something to help us elevate ourselves and to put ourselves on the map.

Three, I think we also need to hold ourselves to a very certain standard. We as consumers need to stop thinking, ‘Oh, well Black businesses are going to overcharge me. Black businesses aren’t as professional. Black businesses aren’t this or aren’t that.’ Us as Black business owners need to set a standard for ourselves that we will try to get away from some of those negative practices. It might be one of us that has that negative practice, but it affects all of us.

Yeah, I’ve heard people say, ‘Well, I’m going to go to a Black-owned business and I am going to spend a lot more money.’ And my thought process was, ‘Well, maybe that’s because they get a lot less capital than white-owned businesses do. So yes, their prices may be a little bit higher.’

Yes. They can’t necessarily afford to go and work with a big brand that might have the ingredient or tool they need to create their product. Whereas a majority-owned business can spend $10,000 on something, the Black-owned business might not be able to spend as much. A lot of times we’re doing it on our own. We don’t have a factory or a warehouse. We don’t have manufacturers. A lot of times, work is done out of our homes or out of small offices. And so it tends to add up in price when you add all those things together.

We’ve heard a lot about boycotts this year. I just wanted to get your thoughts about it because I know there’s a lot of questions from people who are in small, rural communities and the only thing they have is Walmart. So do you have any advice for those people who are in areas where they feel like they can’t boycott because of where they are?

It’s hard to stay out of stores like that, especially when it’s your only option. If you are going to be shopping in those stores regularly, then try to make a switch from a product that you typically would buy from Target or Walmart to a Black-owned version of it. A lot of times there’s a Black alternative.

My advice would be to try your best to have the majority of your cart be from a business that would fall under what is considered DEI. So Black-owned, Latino-owned, Asian-owned, you know what I’m saying? So do your research, find those like Black-owned brands. You can switch up your toothbrush brand at Walmart, which sells Coral Oral – a Black-owned toothbrush brand. That shows Walmart or other corporations like Target, that these Black businesses and these entrepreneurs are worth our dollars to create platforms and [DEI] programs for. It shows the impact that these businesses have on these big-box stores.

You can also switch something out that you would normally buy from Target and buy those items from a small, Black-owned, Latino-owned or diverse business. That will show Target, Walmart and others that rolling back DEI wasn’t a good idea because we can just make a bigger impact with our dollars spent in these other stores.

So that’s what I would say because I do get it. Thankfully I’m in a position where I can wait and order things online. I’m in a city where there are enough Black-owned businesses in my area that I could probably make a switch without having to go into the big box stores.

Since you communicate with these Black business owners, what are they telling you that they need from us right now?

It’s one thing to support one time, it’s another thing to support consistently. Now that people understand that buying Black is something we need to be paying more close attention to, I think people need to understand that it’s more than just a one-time thing, right? How can we make buying Black a regular occurrence for everybody?

As consumers, we’re buying stuff almost every day. So how can we turn our consumer shopping habits into 20, 30 of our purchases coming from or going to Black-owned businesses regularly? Don’t just buy it that one time. Buy it when you get close to running out. Buy it again.