Editor’s note: This report is under revision. We used the words “racial conspiracy theories” as a shorthand and acknowledge that was not the best choice.

Black Americans’ doubts about the fairness of U.S. institutions are accompanied by suspicion. How Black Americans think those institutions impact their ability to thrive is worthy of study, and that’s the purpose of this survey.

Some of the most enduring stereotypes about Black people have their roots in images created during and immediately after slavery. From the docile Mammy and Uncle Tom characters that appeared in newspaper ads and on food containers to the threatening Mandingo in the film “Birth of a Nation” and the more recent controversy about whether television character Olivia Pope was a modern-day Jezebel, Black Americans’ relationship with media has been contentious at best.

Black Americans have also said the news media specifically characterizes them as disproportionately poor, welfare-dependent and criminal. This history of stereotypical imagery provides some context for Black Americans’ beliefs in racial conspiracy theories about the media.

What is a ‘racial conspiracy theory’?

In this report, the phrase “racial conspiracy theories” refers to the suspicions that Black adults might have about the actions of U.S. institutions based on their personal and collective historical experiences with racial discrimination.

A Pew Research Center survey from early 2023 shows that 63% of Black Americans say the news about Black people is often more negative than news about other racial and ethnic groups. Over half (57%) say the news only covers certain segments of Black communities, and 43% say the coverage significantly stereotypes Black people.

In the current survey, nearly nine-in-ten Black Americans (88%) say they at least sometimes come across news and information about Black people they think is inaccurate. This includes 42% who say they come across this often or extremely often and 46% who say they see these inaccuracies sometimes.

And when they come across these errors, Black Americans are more likely to fact-check stories for themselves (85%) than they are to reduce the amount of news they take in overall (52%), from social media (66%), or from friends and family (44%).

Black Americans believe the news media was designed to hold them back

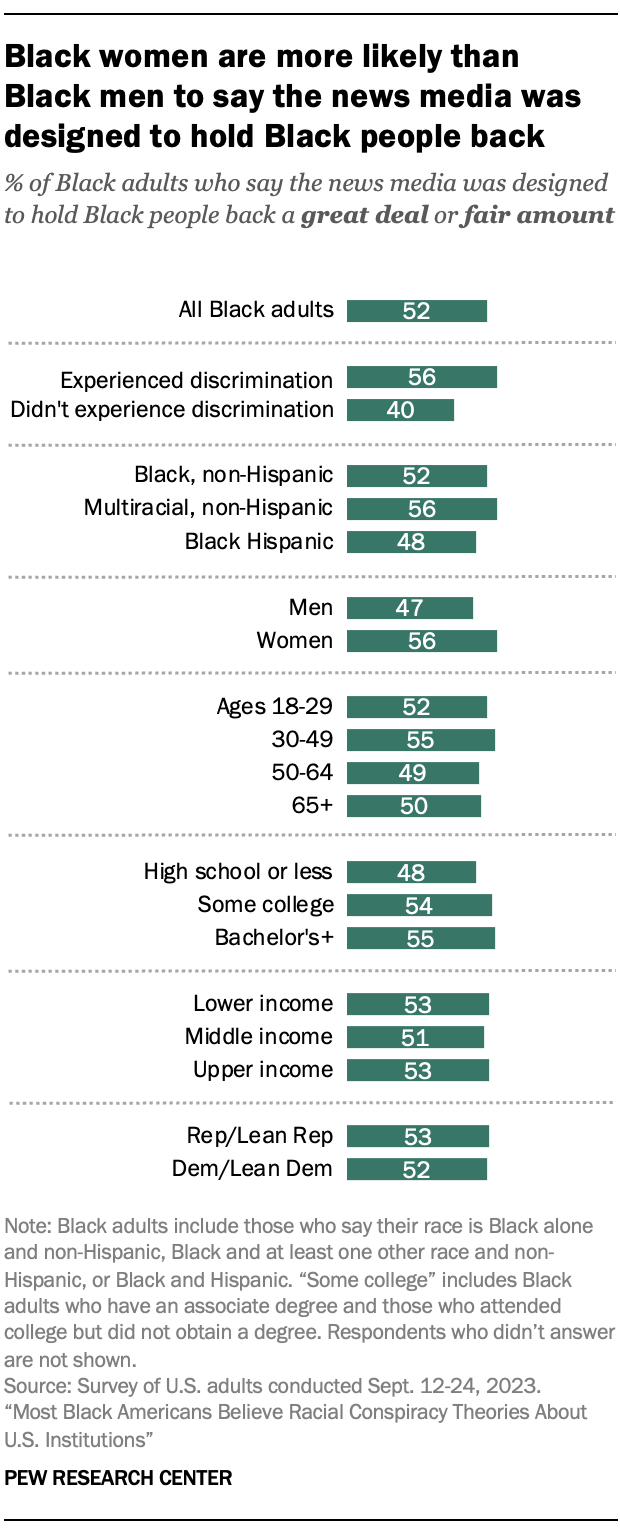

About half of Black Americans (52%) say the news media was designed to hold Black people back a great deal or a fair amount. Fewer say the media was designed to hold Black people back somewhat (30%) or not much, if at all (16%).

Black adults differ significantly on this question by gender. Black women (56%) are more likely than Black men (47%) to say the news media was designed to hold Black people back. Younger Black women are especially likely to agree. Six-in-ten Black women under 50 say this (61%), compared with smaller shares of Black men under 50 (47%) and Black women and men 50 and older (51% and 47%, respectively).

Roughly 55% of Black adults who have been to college say the news media was designed to hold Black people back. This is larger than the share of Black adults with a high school diploma or less education who say the same (48%).

And Black adults who have experienced racial discrimination (56%) are more likely than those who haven’t (40%) to say the news media is designed to hold Black people back.

Most Black adults believe racial conspiracy theories about the media

About nine-in-ten Black Americans (88%) say they come across inaccurate news and information about Black people at least sometimes. And among those who do, 72% say those inaccuracies were created on purpose. Substantially fewer say they are the result of normal human error (24%).

Black adults who have been discriminated against (74%) are more likely than those who haven’t (68%) to say media inaccuracies about Black people are created on purpose.

Black adults with a bachelor’s degree (81%) are more likely than those with some college (74%) or a high school diploma or less education (66%) to say media inaccuracies about Black people are created on purpose. And the share of Black adults with high (80%) and middle (77%) family incomes outpace the share of Black adults with lower incomes (68%) who agree.